Historical stereotypes surrounding the disease label “gout” are an important barrier to effective treatment in contemporary practice

There have been major advances in contemporary understanding about the pathogenesis of gout. Research has shown that gout is a chronic disease of monosodium urate crystal deposition, and, in addition to dietary risk factors, many biological factors including age, male sex, chronic kidney disease, genetic variants, and medications such as diuretics contribute to development of the disease. Nevertheless, most patients believe that gout is primarily caused by dietary factors, especially rich food, alcohol and seafood. Gout may not be viewed by patients as a form of arthritis. The disease is also perceived by patients as an acute illness due to the intermittent nature of flares. [1]

There have been major advances in contemporary understanding about the pathogenesis of gout. Research has shown that gout is a chronic disease of monosodium urate crystal deposition, and, in addition to dietary risk factors, many biological factors including age, male sex, chronic kidney disease, genetic variants, and medications such as diuretics contribute to development of the disease. Nevertheless, most patients believe that gout is primarily caused by dietary factors, especially rich food, alcohol and seafood. Gout may not be viewed by patients as a form of arthritis. The disease is also perceived by patients as an acute illness due to the intermittent nature of flares. [1]

Unfortunately, the lay perception of gout can also influence how health professionals view the illness. Qualitative studies have shown that healthcare professionals view gout as a self-inflicted condition for which dietary solutions are most important and effective, despite no clinical trial data in people with gout to support this approach. [2] Gout may be perceived by healthcare professionals as a disease requiring only acute management. [1] Most people with gout are not treated with effective long-term urate-lowering therapy, and for those patients started on urate-lowering therapy, continuation rates are very low, consistent with an acute view of the illness. [3,4] While symptomatic management alone may be appropriate for those with infrequent flares and low urate crystal burden, many patients with recurrent flares or other indications for urate-lowering therapy are exposed repeatedly to the risks of anti-inflammatory medications such as NSAIDs, colchicine, and high dose corticosteroids without initiation of urate-lowering therapy. [5]

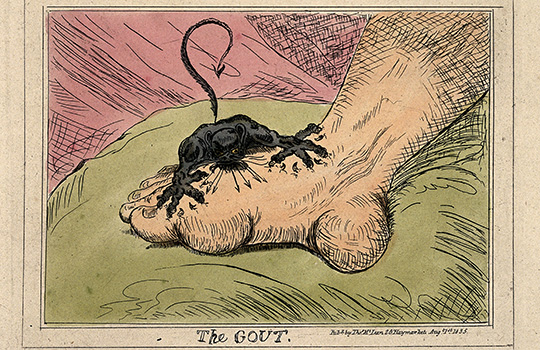

The gout label carries with it considerable social stigma. Many patients report that peers, family members, and healthcare professionals view the illness with humour. [1,6,7] Feelings of embarrassment and shame prevent patients from seeking medical attention due to fear of criticism about their health behaviours. [1, 6]. This view of gout is reflected and perpetuated in popular media. In a content analysis of contemporary US and UK newspapers gout was depicted as a self-inflicted, humorous, and embarrassing condition that is caused by dietary excess. [8]

Throughout history, gout has been depicted as a self-inflicted disease of lifestyle excess. [9]

We believe that the historical stereotypes surrounding the disease label “gout” are an important barrier to effective treatment in contemporary practice. In a recent research study looking into the effect of renaming gout on community perceptions of the illness supermarket shopper participants were randomised to read an identical description of a disease labelled as either “gout” or as “urate crystal arthritis”. [10] The “urate crystal arthritis” label was chosen to reflect the core elements of the condition. In this study, “gout” was perceived as being more likely caused by the patient’s own behaviour through poor diet and overconsumption of alcohol, while “urate crystal arthritis” was more likely to be attributed to ageing. The gout-labelled illness was perceived as being more socially embarrassing and more under the patient’s personal control, while the urate crystal arthritis-labelled illness was viewed as a more chronic and serious condition. For “gout”, changing to a healthier diet was perceived as more helpful, and for “urate crystal arthritis”, taking long-term medications for the condition was viewed as more helpful.

There is a history in medicine of renaming illnesses, both to reduce stigma and reflect the pathophysiological basis of disease. Many historical illness labels are no longer in common use; such as “consumption”, “apoplexy”, “canine madness”, and “dropsy.” Changing the illness label of gout would benefit patients through reducing stigma and removing the pervasive cultural perception of a self-inflicted disease caused by personal indiscretion. For both patients and their health care providers, a change to a pathophysiological name such as urate crystal arthritis would also provide a clearer model of disease and a logical rationale for long-term urate-lowering therapy.

Nicola Dalbeth, Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Auckland.

Keith J Petrie, Professor, Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Auckland.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following: in the last three years, ND has received consulting fees, speaker fees or grants from the following companies who have developed or marketed urate-lowering therapies for management of gout: Takeda, Ardea/AstraZeneca, Cymabay/Kowa, Crealta and Horizon. ND and KP receive research funding from Pharmac (http://www.pharmac.health.nz/), the New Zealand Government’s Pharmaceutical Management Agency.

References:

- Spencer K, Carr A, Doherty M. Patient and provider barriers to effective management of gout in general practice: a qualitative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(9):1490-5.

- Humphrey C, Hulme R, Dalbeth N, Gow P, Arroll B, Lindsay K. A qualitative study to explore health professionals’ experience of treating gout: understanding perceived barriers to effective gout management. J Prim Health Care. 2016;8(2):149-56.

- Solomon DH, Avorn J, Levin R, Brookhart MA. Uric acid lowering therapy: prescribing patterns in a large cohort of older adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(5):609-13.

- Singh JA, Akhras KS, Shiozawa A. Comparative effectiveness of urate lowering with febuxostat versus allopurinol in gout: analyses from large U.S. managed care cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:120.

- Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, Zhang W, Doherty M. Eligibility for and prescription of urate-lowering treatment in patients with incident gout in England. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2684-6.

- Lindsay K, Gow P, Vanderpyl J, Logo P, Dalbeth N. The experience and impact of living with gout: a study of men with chronic gout using a qualitative grounded theory approach. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17(1):1-6.

- Chandratre P, Mallen CD, Roddy E, Liddle J, Richardson J. “You want to get on with the rest of your life”: a qualitative study of health-related quality of life in gout. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(5):1197-205.

- Duyck SD, Petrie KJ, Dalbeth N. “You Don’t Have to Be a Drinker to Get Gout, But It Helps”: A Content Analysis of the Depiction of Gout in Popular Newspapers. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(11):1721-5.

- Nuki G, Simkin PA. A concise history of gout and hyperuricemia and their treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8 Suppl 1:S1.

- Petrie KJ, MacKrill K, Derksen C, Dalbeth N. An Illness by Any Other Name: The Effect of Renaming Gout on Illness and Treatment Perceptions. Health Psychol. 2017; Aug 24, epub ahead of print.