I referred my patient Pat for a specialist opinion. The consultation was not a success. “That specialist registrar you referred me to was totally useless,” said Pat. “What an insolent shmuck! Doc, don’t ever become a registrar.”

I referred my patient Pat for a specialist opinion. The consultation was not a success. “That specialist registrar you referred me to was totally useless,” said Pat. “What an insolent shmuck! Doc, don’t ever become a registrar.”

I don’t know which surprised me more, the insult or the advice. I certainly don’t expect to hear Yiddish slang in the mouths of Oxford patients, and guessed that Pat had probably picked it up from an American drama, such as Suits. What I was sure of was that Pat thought that “shmuck” meant a fool, which it does. He could, of course, have used—had he known them—a wide range of Yiddish synonyms: shlemiel, shlemazel, shmegegge, shmoe, shmol, shnook. Or better still, shlumper, which is not only a shlemiel, shlemazel, and shmoe rolled into one, but also a shlepper, one who dresses abominably, a ragamuffin, and by implication a social outcast, a no-goodnik.

But Pat’s choice was the most barbed of all these—“shmuck” is also slang for the penis. The connection between the penis and stupidity is well established—consider, for example, dick, knob, plonker, and prick. “A man erect does not reflect” as an old proverb has it. A shmendrick is a person who thinks a schlemiel can be educated, but it also means a penis, particularly a small one. Other penis words are shlong (German Schlange, a snake) and shvants (Schwanz, a tail). “And thereby hangs a tail,” as Othello’s Clown jestingly says.

The derogatory sh also decorates slang words for drugs of abuse, typically heroin or cocaine—shit, shmeck (German schmecken, to taste good), and shlock (German, Schlag, a punch). A shmecker is a user, a shlockmeister a dealer. A shnozzle is literally a little nose (German Schnauze, a snout)—the big nosed American comedian Jimmy Durante, of Italian Catholic origin, was known as Shnozzle Durante. But shnozzle is also a cocaine snorter.

Coprolalia is the use of obscene or socially unacceptable words, not merely excremental ones, although it comes from the Greek word κόπρος, meaning ordure. Coprolalia and copropraxia (the use of obscene gestures) are common features of Tourette’s syndrome, as described by Oliver Sacks in his essay “Witty Ticcy Ray” and in Howard I Kushner’s history of Tourette’s, A Cursing Brain. It is no coincidence that coprolalic words that ticceurs commonly use include “shit” and “shite” (German Scheiß), with their pejorative sh.

The origin of all this is of course onomatopoeic—sh is one type of sound that people make when in a derisory or derogatory mood. The hissing phoneme s (the voiceless alveolar fricative) can be turned into sh (the voiceless postalveolar or palatoalveolar fricative) with minimal movements of the lips and tongue. The relationship is exemplified by the fact that in German an s at the start of a word before a p or a t is pronounced sh, as in Spital (“shpital,” a hospital) or Strychnin. Elsewhere, the sh sound at the start of a word is represented by sch. Someone with a cold may sniff (schnüffeln) or sniffle (schniefen), and snuff is Schnupftabak.

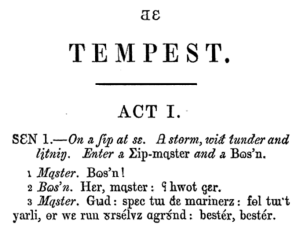

The phoneme sh is represented by the international symbol ʃ, called “esh,” which resembles the integration sign in mathematics, a long ess that stands for “summation.” The symbol was introduced by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz at the end of the 17th century, when he was investigating what we now call calculus. It was then used by Isaac Pitman and Alexander John Ellis to represent the phoneme sh, when they invented the Phonotypic Alphabet in 1845; for words beginning Sh they used an upper case Greek sigma (picture).The esh was later adopted as part of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Variants include the double barred esh, the reversed esh with top loop, and the curly tail esh.

From Alexander John Ellis’s phonetic version of The Tempest (1849), where the lower case and upper case versions of the phoneme sh can both be seen (ʃ and Σ respectively).

In English the contemptuous sh also gives us “shoo!”, “shush!”, and exclamations in which sh and the plosive p for “pah!” are combined, “pshaw!” and “pish!”. A Yiddish trope in which the speaker denigrates the object of attention involves repeating the word for it and adding the prefix shm–. In this way patients can shrug off unpleasant diagnoses, such as an Oedipus complex (“Oedipus Shmoedipus! Shouldn’t I love my mother?”) or cancer (“Cancer shmancer! I’m as fit as a fiddle!”). Or as Pat might have said, “Doctor? Shmoctor!”

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.