“While you’re here, Doc,” said Pat, “would you mind looking at Pat Junior?” It turned out to be a simple upper respiratory tract infection. I recommended something for symptomatic relief. Pat Junior, unimpressed, sniffed snottily. Inevitable really, what with that nasal drip. Perhaps he was disappointed that I wasn’t one of those “famous physicians” who tried to diagnose Christopher Robin’s wheezles and sneezles (picture below).

“While you’re here, Doc,” said Pat, “would you mind looking at Pat Junior?” It turned out to be a simple upper respiratory tract infection. I recommended something for symptomatic relief. Pat Junior, unimpressed, sniffed snottily. Inevitable really, what with that nasal drip. Perhaps he was disappointed that I wasn’t one of those “famous physicians” who tried to diagnose Christopher Robin’s wheezles and sneezles (picture below).

“All sorts of conditions

“All sorts of conditions

Of famous physicians

Came hurrying round

At a run”

“Sneezles” from Now We Are Six by A A Milne.

Illustration by E H Shepard.

A fricative phoneme is one that you produce by forcing your breath through a narrow gap. The phoneme s is an alveolar fricative, made by expelling air past your teeth. And the sound you make when you force air in through the nostrils is similar. We call the result a sniff, which mimics the sound. Conversely, breathing air out forcibly through the nostrils is called a snort, a sound typically made by horses. Sneezing does it even more forcibly.

Charles Dickens knew all about sniffing and snorting. Pecksniff is what he called the snivelling, sanctimonious hypocrite of whom Martin Chuzzlewit falls foul: “Some people likened him to a direction-post, which is always telling the way to a place, and never goes there.” And in Our Mutual Friend (1865) he describes a contretemps between Sophronia Akershem’s aunt, whom he calls “Medusa,” and the horrible old Lady Tippins, in which the former “follows every lively remark made by that dear creature, with an audible snort; which may be referable to a chronic cold in the head, but may also be referable to indignation and contempt.” Lewis Carroll took snorting one stage further—he combined the snort with the chuckle and came up with the chortle.

Sniff, sniffle, snivel, snuff, and snuffle all describe nasal inhalation. Snort can go both ways: a horse snorts by exhaling, a cocaine addict by inhaling. You can also snort heroin, sometimes called horse.

Snoring occurs when the airways collapse during sleep. Snoring can be nasal, oral, or oronasal and can be studied endoscopically during simulated snoring. The risk of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome increases with increasing collar size.

A snout was originally an elephant’s trunk, then an insect’s proboscis, or a bird’s beak, or the part of an animal’s face that includes the nose and mouth. It was then used to describe a human nose, particularly an ugly one. And just as a nose is a police informant, so is a snout, like a sneak or a snitch. Why snout also means tobacco is not known, but perhaps it was something to do with the type that you snort: snuff.

To snoop is to be nosy and to snub someone is to turn up your nose at them.

Snotty means full of nasal mucus and was once also a nickname for a midshipman, perhaps, as Hunt and Pringle delicately put it in Service Slang, a First Selection (1943), “after the buttons on his sleeve, which are said to be there for a purpose not unconnected with the nickname.” Snotty also, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, means snooty, through an old error of confusion. James Joyce made it in a letter to a friend in 1905: “Are the ‘girls’ ‘snotty’ about Nora [Barnacle]?” Of course, being Joyce, he may have confounded the two words intentionally. Other offenders, all quoted in the OED, have included Wilfred Owen, Ernest Hemingway, and Lord Reith (“I was very snotty and reserved with the prig”). The OED records the snooty meaning of “snotty” because it records usage, without, except in rare cases, commenting on what is supposedly correct or preferable.

A colleague recently emailed to say that a paper we had authored had passed the 100 citations mark on Google Scholar. I replied in what I intended to be a mildly jocular fashion (including a smiley emoticon, to make the point), joshing him about counting citations. Another co-author then accused me of being snooty, although what he actually wrote was “snotty.” I wondered how he knew that I had a bad head cold at the time. :>)

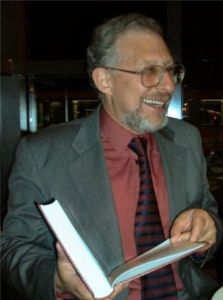

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.