Emily Colas’s Just Checking is a riveting, often unsettling, account of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Reading it got my stream of consciousness ruminating about the link between disgust and stereotypy.

Emily Colas’s Just Checking is a riveting, often unsettling, account of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Reading it got my stream of consciousness ruminating about the link between disgust and stereotypy.

Neasden is a byword for ordinariness; Wigan for northernness; and East Cheam, at least since Tony Hancock, for supposed rundown provinciality.

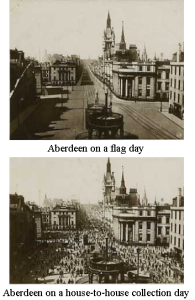

Aberdeen is associated with miserliness (picture), although that may be a canard that Aberdonians foster to avoid expenditure :). And Tunbridge Wells is stereotypically associated with disgust.

Aberdeen is associated with miserliness (picture), although that may be a canard that Aberdonians foster to avoid expenditure :). And Tunbridge Wells is stereotypically associated with disgust.

“Disgusted, Tunbridge Wells” describes someone with strongly conservative political views, who writes outraged letters to newspapers. “Your obedient servant, ‘Disgusted’” appeared in a letter to The Times in 1884. The full phrase is thought to have been introduced in the BBC radio show Much Binding in the Marsh in the 1940s, by comedian Richard Murdoch (1907–90), last seen on television playing Uncle Tom in Rumpole of the Bailey, but famous over many years for radio shows such as Band Wagon and The Men from the Ministry. Wallas Eaton played a character called “Disgusted, Tunbridge Wells” in another radio show, Take it From Here.

When the BBC called a complaints programme Disgusted, Tunbridge Wells in 1978, the Kent & Sussex Courier reported that those living in Tunbridge Wells were disgusted. But Tunbridge has long been belittled; in E M Forster’s A Room With View (1908) Charlotte Bartlett says “I am used to Tunbridge Wells, where we are all hopelessly behind the times.”

Disgusted comes from the Latin privative prefix dis- plus the verb gustare, to taste. Dislike the taste of something? Spit it out—puh! And the same sound, the voiceless bilabial plosive phoneme p, expresses disgust for anything. “Pah!” says Hamlet, disgusted by the smell of Yorick’s skull. King Lear is even more emphatic: “There’s hell, there’s darkness, / There’s the sulphury pit, burning, scalding, / Stench, consummation. Fie, fie, fie, pah, pah! / Give me an ounce of civet, good apothecary, / to sweeten my imagination.”

When p becomes b (the voiced bilabial plosive) we get bah. Pooh-Bah, the “Lord High Everything Else” in the Mikado, is onomastically doubly disgusting. “Pooh-Bah,” wrote G K Chesterton, “is something more than a satire; he is the truth. It is true of British politics . . . that we meet the same man twenty times as twenty different officials . . . The general result can be expressed only in the two syllables (to be uttered with the utmost energy of the lungs): Pooh-Bah.”

The Indo-European root PU, decay or rot, gives us words that reflect repugnance. Greek πύον (puon) and Latin pus give us pyaemia, empyema, and pyorrhea, pustule, purulent, and suppuration. From Greek πῡτιζειν (putidzein), to spit out, comes πτύαλον (p’tualon), saliva. Ptyalin is the salivary amylase that catalyses the hydrolysis of polysaccharides. Ptyalism is a rare adverse reaction to digitalis and artemisinin; it can also occur in pregnancy (ptyalism gravidarum), when it is associated with hyperemesis.

Latin putris, rotten, gives putrid, putrescent, and putrescine (tetramethylenediamine), a foul smelling amine formed by the breakdown of amino acids in putrefying dead flesh. Putrescine and cadaverine contribute to the odours of halitosis and bacterial vaginosis.

The polecat family is Putorius foetidus and a putois is a paintbrush of polecat’s hair. A polecat was once a slang term for a prostitute, as were pucelle and putain, loan words from the French. Consonantal shift of p to f gives foul, filthy, and defile. A fulmar is a foul smelling gull-like bird of the petrel family. Polecats are also called foumarts (foul martens).

If you pronounce “pejorative” as it used to be pronounced, with the accent on the first syllable, you get the full force of the disgust it conveys. Other words beginning with a p have similar force: pee, piss, and pish, pimp, pizzle, pox, prick and prig, punk, and the childish words for excrement poo and poop. On seeing them grunting and squelching in the mire, Rowley, the old farm labourer in Crome Yellow by Aldous Huxley, voices his disgust: “Rightly is they called pigs.” Stress the p when you say it.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.