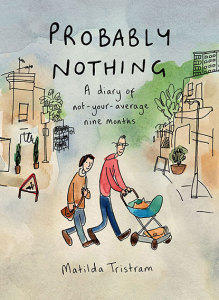

Probably Nothing is a comic by Matilda Tristram about discovering that she had colon cancer when she was 17 weeks pregnant. The comic, initially published online and now as a book, charts her diagnosis and subsequent treatment while pregnant and then looking after a newborn baby. It is a very honest and moving account of what it is like to be a patient.

Probably Nothing is a comic by Matilda Tristram about discovering that she had colon cancer when she was 17 weeks pregnant. The comic, initially published online and now as a book, charts her diagnosis and subsequent treatment while pregnant and then looking after a newborn baby. It is a very honest and moving account of what it is like to be a patient.

The comic is beautifully but simply illustrated, and portrays the range of emotions that Tristram went through perfectly. This is most uncomfortable when describing the battle she had to persuade doctors that there was something seriously wrong. Her symptoms were initially considered to be pregnancy related, and after a weekend in A&E she had to plead with a doctor to get a MRI scan. “The problem is that the MRI machines aren’t owned or managed by the NHS . . . we need two doctors’ signatures and their consent, there are waiting lists . . . ,” he explained.

However, despite the delay in being diagnosed, the comic is enormously positive about the doctors and nurses who treated Tristram, and the NHS in general, particularly the fact that the treatment is free. At one point Tristram writes, “Read about the privatisation of the NHS and feel worried—no one would insure me now.” Her treatment would, she says, cost $150 000 (£92 740; €118 620) in the US.

The book illustrates the practical difficulties of living with cancer, for example: having to sleep with a chemotherapy pump attached, the discomfort of having a peripherally inserted central catheter put in, the indignity of a colostomy bag suddenly leaking everywhere, and having hands so swollen and painful from steroids that she couldn’t open her birthday presents. There are also plenty of funny moments, such as Googling colostomy bags and all the ads on her laptop then being for colostomy products. “I can never use my laptop for teaching again!” she says.

The book illustrates the practical difficulties of living with cancer, for example: having to sleep with a chemotherapy pump attached, the discomfort of having a peripherally inserted central catheter put in, the indignity of a colostomy bag suddenly leaking everywhere, and having hands so swollen and painful from steroids that she couldn’t open her birthday presents. There are also plenty of funny moments, such as Googling colostomy bags and all the ads on her laptop then being for colostomy products. “I can never use my laptop for teaching again!” she says.

It is the emotional toll of having cancer that is so well observed. Tristram describes the enjoyment of doing normal things, like putting on make-up and going out, and then suddenly crying over them, or seeing the same old stuff at home when everything else is so different. She says that when doctors ask her, “And how are you coping generally,” it always makes her want to cry. The comic changes pace quickly so the reader experiences the ups and downs with her. One moment is full of funny or mundane details of everyday life, and the next shows the enormous and constant levels of stress and anxiety that she had to endure.

Tristram is also very honest about how she gets touchy when people ask too many questions about her treatment, or talk about the time they thought they had cancer—but didn’t, or tell her about people they know who had cancer. “The ratio of cancer to normal chat has to be right,” she says. She doesn’t like people telling her that she has to remain positive, as though if you’re not positive you’re more likely to die. There are also some cancer euphemisms that she tries to debunk. “It’s not a story, it’s real. It’s not a journey, I’m not going anywhere. And I’m not ‘battling.’”

What struck me was how Tristram managed with the treatment despite being pregnant and then looking after a newborn baby. The difficult decision that Tristram and her partner had to make about the baby was spelt out in no uncertain terms. The oncologist told them that, “As I see it, you’ve got three options: have chemo now and risk damaging the baby, terminate the pregnancy and start chemo after that—and I must make you aware that chemo could make you infertile, or delay treatment until after it’s born.”

When her son James was born by caesarean section, he had to go to the special care baby unit and it took 12 hours until Tristram was able to see him as no one could find a wheelchair to take her in. At the same time, her stepfather wasn’t allowed in to see her because of the risk of infection, but the Bounty woman, who was distributing freebies to new parents, was. As Tristram says, “Surely the Bounty woman is more likely to spread infection by visiting everyone.”

It seems strange to write that this is a very enjoyable book, but Tristram’s illustrations and writing are so engaging that it is. It also provides a great insight into what it is like to be a patient. I would recommend it not only as a good read, but because there is a lot for healthcare professionals to learn from it. Although she is honest about the things that went wrong with her care, the overall message of the book is very positive.

Juliet Dobson is web editor and blogs editor, The BMJ.