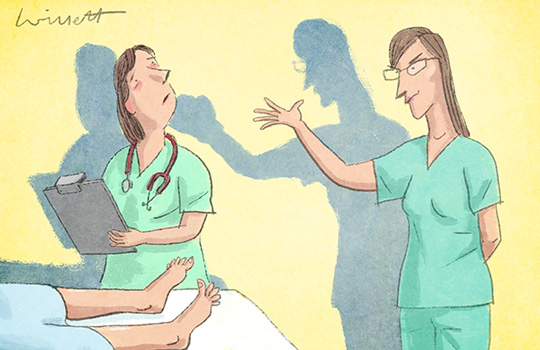

Bullying is a patient safety issue and often a signal of wider cultural issues within an organisation. Compassionate leadership can change culture, empower staff to speak up, and address bullying and undermining behaviours in an organisation, say Iona Thorne and Zoe Oliphant

Over the past year, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) has adapted its methodology to strengthen its assessment of leadership and culture, using the “well-led” framework. As well as damaging individuals involved, bullying is an important patient safety issue and often represents endemic cultural issues within a healthcare provider.

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) and Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG) recently convened 130 healthcare leaders to discuss practical solutions to tackle bullying, harassment, and undermining behaviour in the healthcare system. The link between the wellbeing of those delivering care and those receiving care has a well-established evidence base. At the event, Jim Mackey (CEO Northumbria NHS, and until recently, chief executive of NHS Improvement) described the NHS as a “human business, about people.“ He also warned that staff are more likely to be bullied in environments facing pressure on clinical systems. Compassionate and inclusive leadership has an important role in addressing organisational cultures affected by bullying and undermining behaviours to ensure the value placed on providing compassionate care for patients is extended to all staff.

Negative staff experiences are often a precursor for negative patient experiences. RCSEd highlights that disruptive behaviour around the time of an operation contributed to 67% of adverse events, 71% of medical errors and 27% of peri-operative deaths. Chris Turner, from the “Civility Saves Lives” project focused attention on the issue at the event, saying “when we permit rudeness, our patients die unnecessarily.” The victims of bullying have a reduction in cognitive ability, loss of hand-eye coordination, and the experience drives people to “freeze.” Bullying also impairs performance, reduces compassion in onlookers, and drives anxiety in patients and relatives.

Bill Kirkup’s review of Liverpool Community Healthcare Trust (LCHT) found cases where staff were bullied and harassed when they tried to raise concerns about falling standards in patient services. This culture of bullying co-existed with staff being overstretched and demoralised. When staff reported difficulty maintaining safe and effective services in the context of staff reductions, they did not feel listened to. Middle management responses “included extreme action against more junior staff, amounting to bullying” and there were “repeated accounts that staff would be suspended without being told why, or what the next steps would be.” Staff worked in “a culture of intolerance, disbelief and fear’ with ‘excessively top-down management’ and ‘a punitive and blame culture.”

Given their focus on ensuring providers are delivering safe, high quality patient care, the CQC takes bullying seriously, and the well-led framework emphasises the importance of leadership and culture within an organisation. The framework echoes Good Medical Practice “to maintain good relationships with colleagues” and General Medical Council (GMC) guidance around “building a supportive environment.“ The CQC partners with the National Freedom to Speak Up Guardian’s Office, supporting local Guardians in every NHS trust. To speak up, staff must feel safe, sure that concerns will be investigated and well-received, and confident that speaking up will make a difference. The CQC asks questions about culture during interviews with staff on inspections, around their experiences or observations of bullying, support available, and confidence to raise issues. Where bullying and undermining behaviours are found, it has been identified in inspections reports, and recommendations are made that require action to be taken in response.

The CQC publication “Driving Improvement” reviewed significant drivers for improvement at NHS trusts achieving significant improvement in ratings between inspections. These case studies found that the leaders had a pivotal role in developing a culture of openness and transparency, and highlighted the importance of visible, approachable leadership, moving the culture of the organisation from one of blame to celebrating success. Staff engagement and empowerment were also seen to be a driver for improvement.

Bullying may extend up to senior leaders in an organisation, and poor attitude at a senior level may filter to all parts of the organisation. The “Fit and Proper Person Requirement” describes leadership requirements for senior directors. NHS Providers has recently published a briefing offering practical suggestions to ensure trust policies and procedures comply with the Fit and Proper Persons regulations.

Performance management should empower staff to work effectively and in line with an organisation’s objectives. However it strays into bullying when executed in an undermining or overbearing way, when it is no longer constructive but demeaning to the individual, and when it hinders progress at an organisational level. Similarly, quality assurance and accountability processes should not have bullying undertones.

Compassionate leadership builds a culture of improvement and creates psychological safety to empower staff to raise concerns and make suggestions.

Zoe Oliphant is a surgical registrar in Severn Deanery. She is a National Medical Director’s Clinical Leadership Fellow, working for the Chief Inspector of General Practice and Integrated Care at the Care Quality Commission.

Iona Thorne is a medical registrar in London. She is one of the National Medical Director’s Clinical Leadership Fellows, working for the Chief Inspector of Hospitals at the Care Quality Commission.

Iona Thorne is a medical registrar in London. She is one of the National Medical Director’s Clinical Leadership Fellows, working for the Chief Inspector of Hospitals at the Care Quality Commission.