More and more, organisations are seeking to push the envelope towards “co-production” of research

Over recent years the UK and US have embedded the principle and informed practice on how to involve patients and the public as partners in health and social care research. In the UK, the movement has been led by INVOLVE, which was set up in 1996 and is now integrated with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). In the US, this work is being led by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). But they are not the only players here. Interest in patient and public involvement (PPI) in research is international, and many different national organisations are seeking to push the envelope towards “co-production” of research.

Over recent years the UK and US have embedded the principle and informed practice on how to involve patients and the public as partners in health and social care research. In the UK, the movement has been led by INVOLVE, which was set up in 1996 and is now integrated with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). In the US, this work is being led by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). But they are not the only players here. Interest in patient and public involvement (PPI) in research is international, and many different national organisations are seeking to push the envelope towards “co-production” of research.

Earlier this week representatives met in London to lay the foundations for a global network (#globalPPInetwork) that is dedicated to making research an enterprise done “with or by” patients and the public, rather than “about or for” them.

The ethical imperative to involve patients and the public in research that they directly or indirectly fund, and which is carried out on them in their name, is widely accepted. There is also a growing consensus that their involvement is one of the key ways of increasing the value and reducing waste in the biomedical research enterprise. Furthermore, there is evidence that co-producing research with patients and the public provides an appreciable “return on investment.”

Yet the challenge of turning PPI in research into a global “social movement” should not be underestimated. In some countries and cultures, working with patients, carers, and civil society groups as partners to improve health and social care is far from an accepted norm. The new network will need to change culture, as well as share innovative approaches and best practice on methodologies of PPI in research, the meeting agreed.

It’s always stimulating to debate the vision, remit, and outputs of a new enterprise and the scene was set with energy by Simon Denegri, the NIHR’s national director for patients and the public in research, and lead members of the meeting’s co-host organisations. These included Richard Morley from Cochrane, Heather Bagley from the COMET (Core Outcomes Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiative, and Professor Sophie Staniszweska from the University of Warwick. To kickstart debate, survey data from 46 different national organisations concerned with PPI in research were presented, setting out their suggested priorities for action for the new network. Top of the list were developing and sharing information on training/learning about PPI, setting standards and policies, sharing know-how in the form of guidelines and other ” tools,” supporting organisations to develop a robust PPI infrastructure, and assessing the impact of PPI in research.

Aspirational thinkers jumped in fast. “Let’s get Bill Gates, WHO, Google DeepMind in to back it, and the global health research community.” “In two year’s time let’s aim to be the most talked about network on social media.” Pragmatists focused on the readily achievable: “Let’s start by collating information on existing resources.”

There were then the usual calls to avoid reinventing the wheel and duplicating the work of existing networks. A cogent comment to this effect came from Chi Pakarinen, project manager for the Patient Focused Medicines Development programme. She flagged that under this programme, which is a component of The Synergist initiative, a “landscape” mapping tool has already been set up to log and promote international learning from PPI initiatives. This then fostered further discussion on the extent to which the new network should work with pharma’s PPI in research initiatives, and other initiatives, such as the European Patients’ Academy.

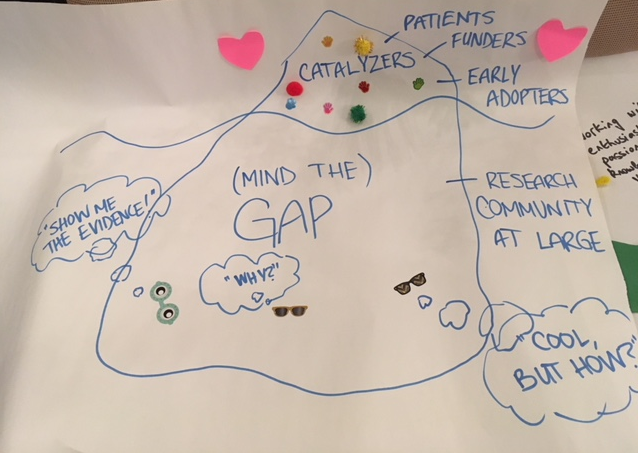

Halfway through the day participants were asked to draw (or create in 3D) their vision for the network. Tables were organised by nationality, which ensured competition on this task was fierce. The Canadians won the day. Their poster depicted an iceberg (pictured below). The visible top represented the people and organisations in the room: early adopters already passionate and knowledgeable about PPI in research. But under the water lurks a larger two part constituency. The “Well PPI is a cool idea but how on earth do you do it?” group, and the “Hmm . . . show me the evidence that all this works and is helpful” group. A warning was then issued that the network must avoid preaching to the converted and ensure it reaches out to the hearts and minds of those “below” the water line.

Other national perspectives emerged, including “the Scottish paradox.” Louise Locock, professor of health services research at the University of Aberdeen, pointed out that while Scotland is widely seen as a leader in patient centred care, it only funds one (part time) person to embed PPI in research. Victoria Thomas, head of public involvement at NICE, pointed to another conundrum: the persistent tendency to put qualitative research—which is relevant and important in relation to a lot of the work around PPI—down the bottom of the research hierarchy. One issue where all were in agreement was that there is a need to shift the power balance between researchers and patients, for it still remains firmly skewed towards the former.

Tessa Richards, The BMJ.

Note: The international network for public involvement and engagement in health and social care research is planning to meet again in spring 2018. To read more about the network, and to take part in their survey, visit http://consumers.cochrane.org/news/international_network You can also email Gary Hickey at gary.hickey@nihr.ac.uk