Polls continually show a majority of Americans support reasonable gun policies, and yet the US has not been able to address its firearms problem

The United States has a gun problem. On an average day, 300+ Americans are shot, and about 100 die. There have been more civilian gun deaths since Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968 than there have been Americans soldiers killed on the battlefield in all our wars.

The United States has a gun problem. On an average day, 300+ Americans are shot, and about 100 die. There have been more civilian gun deaths since Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968 than there have been Americans soldiers killed on the battlefield in all our wars.

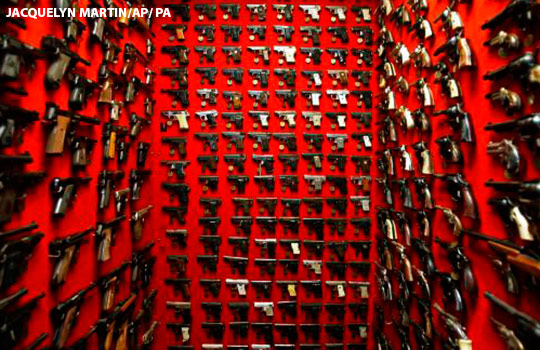

Compared to the world’s other two-dozen high-income countries, the United States is an average nation in terms of (non-gun) crime and violence. However, we are an outlier in terms of guns and gun violence. We have many more guns than other developed countries, the most permissive gun laws, and far more gun deaths per capita.

We also have more mass shootings per capita. Yet there is no evidence that US citizens are more mentally unstable or suicidal than citizens of these other countries or that we have more psychopaths and monsters.

Our mass shootings have been increasing in frequency in recent years. These shootings appear to be somewhat contagious. The event—and the shooters—receive a large amount of media attention that seems to inspire further mass shootings. Our stock of guns has also recently become more militarized, with guns that can kill more people more quickly.

Each mass shooting is unique. Unusual in the Las Vegas shooting was the older age of the shooter (most shooters are aged 20-50), the large physical distance between the shooter and victims, and the use of machine gun-like weapons that could fire 9 rounds per second.

Most people outside the US do not understand why the US does not address its firearms problem, especially since polls continually show that the large majority of Americans support most reasonable gun policies. Here is my personal and overly simplistic (due to space constraint) explanation.

Firstly, it has nothing directly to do with the Second Amendment of the US Constitution. Fewer than 10 years ago was the first time that the US Supreme Court (in a 5-4 decision) ruled that the amendment did not involve state militia after all, but instead guaranteed each individual the right to own a handgun in his own home. Still, since then the courts have found that almost all state gun laws (except those that effectively ban having guns in the home) pass constitutional muster.

So why has it been so difficult to change US policy? One should not underestimate the importance of race underlying many US laws (e.g., our criminal justice, welfare, and immigration policies). There is too often little societal sympathy for black people who are disproportionately more likely to be the victims of interpersonal gun violence. And imagine the response if the perpetrator of the Las Vegas massacre had been a black or Muslim person rather than a white person

In the 1960s, when President Lyndon Johnson, a Texas Democrat, pushed through civil rights reform, the Republican party adopted its “Southern Strategy.” The old Confederacy, which hated Abraham Lincoln’s Republican party for more than a century, quickly turned from a Democratic stronghold to a solid Republican one. Southerners own about half of US guns and Southern (and rural) states have the weakest gun laws. The Republican party is now America’s pro-gun party.

Gerrymandering has turned the vast majority of Congressional districts into “safe seats” for either the Republicans or Democrats. The only threat to incumbents is in the party primary elections where the concern is not to represent the middle, but to ensure that one is not outflanked by the far right or the far left. The far right for Republicans is usually even more pro-gun.

In the United States, single-issue lobbies like the National Rifle Association (NRA) have disproportionate power compared to such lobbies in most other countries. The positions of the leaders of such lobbies are typically more extreme than their members. While the majority of NRA members support many reasonable gun policies, the NRA leadership is strongly opposed. Leaders garner more financial support if they can convince members that the “other side” is always up to something nefarious, such as trying to take away all their guns.

NRA positions always are consistent with increasing gun sales and profits, but their political power probably comes less from the money provided by the gun industry than by grass-roots support. There are thousands of loyal followers who can be quickly mobilized to call, write letters and email their representatives, attend political hearings, and cast their votes determined solely by the candidate’s position on gun policies.

A related problem for gun control in the US is that the legislators do not look like the general population. Groups most in support of gun control (e.g., women, minorities) are disproportionately underrepresented among state and federal legislators. The typical member of Congress is male, white, older, and rural—which is the same demographics as the typical US gun owner.

But change is possible. A great US success story is California. Beginning in the early 1990s, the Wellness Foundation helped jump-start the change, providing over $100 million for firearms data collection, research, and advocacy. Today California has the strongest gun laws in the country, and firearm fatalities have dropped substantially. So not only can we look to the other developed nations for inspiration and guidance, but we can also look west to our most populous state.

David Hemenway is professor at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health and author of “Private Guns Public Health” (2006, 2017).

Competing interests: DH is currently co-investigator on a research grant to study gun violence from the Joyce Foundation in Chicago, one of whose missions is to build safer communities through sensible gun violence prevention policies.