In an earlier blog I noted the impossibility of knowing which words came first, language having evolved thousands of years before written records, although claims have been made for the longevity of words such as I, we, and thou; this and that; who and what. One can, however, discover the earliest known recorded words in English, by searching the Oxford Engish Dictionary, which itself draws on information given in earlier dictionaries, glossaries, and encyclopaedias, sometimes collectively known as lexionaries, as well as primary texts.

In an earlier blog I noted the impossibility of knowing which words came first, language having evolved thousands of years before written records, although claims have been made for the longevity of words such as I, we, and thou; this and that; who and what. One can, however, discover the earliest known recorded words in English, by searching the Oxford Engish Dictionary, which itself draws on information given in earlier dictionaries, glossaries, and encyclopaedias, sometimes collectively known as lexionaries, as well as primary texts.

Early Old English glossaries included Latin–Latin glosses and English translations of Latin words. The earliest known was the 7th century Mercian Epinal glossary, now kept in Épinal in France. A copy of the Epinal glossary, the Erfurt glossary, is kept in Erfurt in Germany and a third version, the Corpus glossary, in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Others included the Aelfric, Aldhelm, Antwerp, Cleopatra, Harley, and Leyden glossaries.

The Epinal glossary included a dozen or so medical words, here given in the original Latin with the Old English form and the standard English spelling and definition, where needed.

Basis, teter; Inpetigo, tetr; Papula vel pustula, spryng vel tetr (tetter, a general term for eruptions such as eczema, herpes, impetigo, ringworm)

Bile, átr (atter, gall or bitterness)

Cartilaga, næsgristlae (gristle, cartilage)

Gurgulio, throtbolla (throat-boll, the Adam’s apple)

Liuida toxica, tha uuannan aetrinan (wan, of an unhealthy, unwholesome colour; livid, leaden-hued; applied especially to wounds, to the human face discoloured by disease, and to corpses)

Malagma, salb (salve)

Obligamentum, lybb (lib, a drug or potion used as a charm)

Pollux, thuma (thumb)

Senecen, gundaesuelgiae (groundsel)

Singultus, iesca (yex or yesk, a sob, a hiccup, or the hiccups)

Uarix, ampræ (amper, a tumour or swelling)

Uessica, bledrae (bladder)

The glossary also included words for plants that may have been used as therapeutic herbs, such as cress, dill, elder, fennel, gladdon, hazel, sallow, sowthistle or thowthistle, and waybread. It also mentioned Cicuta, hymblicæ, water hemlock (Cicuta virosa).

Earlier examples might be found in the Dictionary of Old English Corpus in Electronic Form, a database of three million Old English words, only 1% of which comes from Old English glossaries. However, those in the Epinal glossary will do to be going on with.

On the other hand, medical texts existed long before English glossarists found it necessary to translate the relevant texts into English. I therefore asked my friend and colleague Bob Arnott, a medical archaeologist and historian, to tell me what he thought the earliest medical word in any language was. Here is his reply:

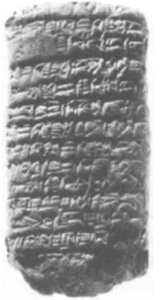

“The very earliest medical texts are to be found in the Ancient Near East and are Sumerian, from what is called the Ur III period (c.2050 BC). Written using the cuneiform script on clay tablets, they are a series of diagnostic manuals, remedies, and incantations. One of these tablets, now in the Hilprecht Collection in Jena in Germany (number HS2438), was found in the city of Nippur (city of the god Enlil). It is therefore safe to award it the accolade of containing the oldest known medical word. The tablet itself contains an incantation for the cure of a headache (or the ‘headache demon’) that distresses the neck muscles. The remedy is rubbing in a mixture of purifying water and the fat of a cow, plus the appropriate incantation.”

Bob’s choice of word was therefore sag-gig, the Sumerian for headache (picture).

A headache tablet. Part of the cuneiform tablet HS2438 and below “sag-gig” in cuneiform

A headache tablet. Part of the cuneiform tablet HS2438 and below “sag-gig” in cuneiform

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.