Which words came first? And whence comes “first?”

Which words came first? And whence comes “first?”

In his Historiai, Book II, Herodotus tells how an Egyptian king, Psamtik (he calls him Psammetichus), undertook an experiment. He entrusted two children to a herdsman, charging him to allow no one to utter a word in their presence, to keep them in a cottage and to care for them, from time to time allowing goats into their apartment to supply them with milk. Two years passed, and one day, when the herdsman entered their room, the children ran to him and clearly said βηκος (bēkos), the Phrygian word for bread.

Herodotus’s account of Psamtik’s linguistic experiment, true or not, makes good reading. But did their caprine contacts cause the children to say “beeeeeh-kos?” In Greek βηκία (bēkia), as used by Hippocrates (cited by Galen), meant little sheep. Baaaaah!

Speech is prehistoric, having emerged many thousands of years ago, and we cannot possibly know what the first spoken word was. There is even debate about who might have uttered it. Did it emerge with homo sapiens? Neanderthals were supposedly incapable of it, lacking as they did the requisite anatomical apparatus, but the discovery that they possessed a hyoid bone suggests otherwise.

On the other hand, there is abundant linguistic and archaeological evidence of proto-languages, the precursors of those we speak today. Latin is an obvious direct forebear of modern Italian, and ancient Greek of modern Greek. And languages can develop in different ways from common ancestors—compare modern French and Canadian French, or Portuguese and Brazilian. But proto-languages go back much further than any of these, being the earliest attested or hypothetically reconstructed forms of languages, including such gems as proto-Algonquian, proto-Athapaskan-Eyak, and proto-Hattic. Best known is proto-Indo-European, and its discovery contained a surprise: that there was a single linguistic forerunner of most Indian and European languages.

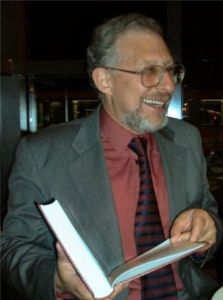

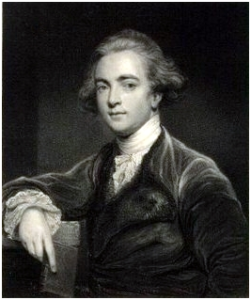

Sir William Jones, an English judge (pictured), whom Dr Johnson described as “the most enlightened of the sons of men,” came to Calcutta in 1786 and tackled Sanskrit—a tough task.

Sir William Jones, an English judge (pictured), whom Dr Johnson described as “the most enlightened of the sons of men,” came to Calcutta in 1786 and tackled Sanskrit—a tough task.

Sir William Jones (1746–94). Steel engraving from the portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds

As Monier Williams tells us on page one of his Sanskrit Grammar (1857), devanagari, the Sanskrit script, had 14 vowels (all but one having two forms), 33 simple consonants, and 400–500 conjunct consonants. But Jones mastered it and made his discovery: “No philologer could examine [Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin] without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.”

Thomas Young, discussing Johann Christoph Adelung’s Mithridates, oder Allgemeine Sprachenkunde (Quarterly Review, October 1813), called that common linguistic source “Indo-European.” And in 1916 Carl Darling Buck introduced the term “proto-Indo-European” to describe the theoretical roots from which modern words are thought to have developed.

Now take the hypothetical root PER, meaning “through” or “in front,” the latter in two senses: front running and confronting (compare “persuasion” and “perdition”). Different subroots of PER in Greek yielded πρóς, in front, πᾰρά, alongside, and περί, around; and in Latin pro, before or for, praeter, beyond, and per, through. One’s profile features one’s face and prosopagnosia is an inability to recognise faces. Prose is straightforward writing, unlike verse, which turns around line by line.

William Prout hypothesised that hydrogen’s primordial positively charged particle was the basic matter of which all elements were composed; Rutherford called the particle a proton. Prolactin is secreted before lactation, progeria is precocious senility, a prodrug is a precursor of an active one, and preproparathyroid hormone has a lot of previous.

But consonants change. Plosive p in Greek and Latin becomes fricative v and f in Germanic, and PER gives us forbid, foremost, before, former.

“One” comes from the root OINO, but its ordinal forms in Indo-European languages generally derive from PER (French un/premier, Italian uno/primo, German ein/erste). So at last we understand “first.”

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.