Social media during epidemics: a poisoned chalice?

5 Jan, 15 | by BMJ

Social networking is now the most popular online activity worldwide. Social networking sites account for nearly 1 in every 5 minutes spent online globally, reaching 82 percent of the world’s Internet population. As such, sites such as Facebook and Twitter have become an unavoidable part of crisis communication. However, opinion is mixed as to whether this pervasiveness is a blessing or a curse to organisations charged with protecting public health. The very attributes that make social media invaluable to communicators (instantaneous, wide-reaching) also make it incredibly difficult to control and moderate.

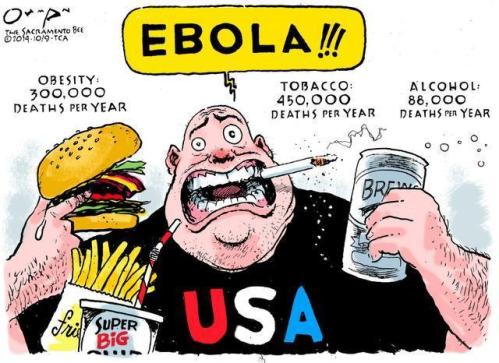

One concern about social media is that it has the potential to generate and perpetuate rumour. Following the first diagnosis of an Ebola case in the United States on 30th Sep 2013, mentions of the virus on Twitter leapt from 100 per minute to more than 6,000. In Iowa, the Department of Public Health was forced to issue a statement dispelling social media rumours that Ebola had arrived in the state. Meanwhile, a steady stream of posts claiming that Ebola can be spread through air, water and food appeared; all of which are inaccurate.

Trying to stem the spread of incorrect information online shares many similarities with containing a virus in the real world. Internet users who have been given false messages from an inaccurate media report, another person on social media or word-of-mouth, proceed to “infect” others with each false tweet or Facebook post. “We have millions and millions of people on these social networks,” says Ceren Budak, a researcher who studies online communications at Microsoft Research. “Most of them in certain cases are not going to have reliable information, but they’re still going to keep talking.”

Part of the issue is thought to be the piecemeal way in which news is now consumed. According to a Pew Research Center study, almost a third of US adults get at least some of their news from Facebook, where recognised sources are competing with friends and relatives. Studies show that people are far more likely to trust information that comes from people they know than faceless organisations. This is how a single false statement on Twitter can affect thousands.

However, a report produced by the TELL ME project argues that “whilst on an open platform such as Twitter, users are free to post any message…the vast collaborative networks that comprise social media often question and correct rumours posted”. Whilst there is more information online than ever before, users have learned to verify information and question where it is from. “Whilst the ‘citizen journalist’ can report on events ahead of reports by other media outlets or organisations, users are still wary of sources and, even on Twitter, hold official sources in high esteem, often seeking verification before believing alarmist messages”.

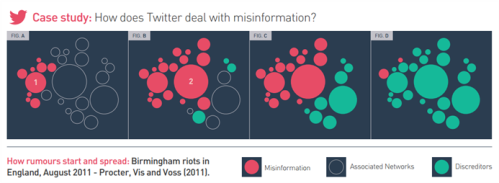

The Guardian did a great job of illustrating how one user’s tweet was retweeted several times during the Birmingham riots in England, August 2011, leading to a rapid spread of misinformation. Within half an hour the rumour of riots in a Birmingham children’s hospital spread through the simple process of people retweeting a dramatic and unfounded tweet. Despite this misinformation gaining momentum, within a period of two hours, the Twitter community was able to discredit the rumour. This demonstrates that users of social networks readily collaborate to make informed decisions on the quality of information they are receiving.

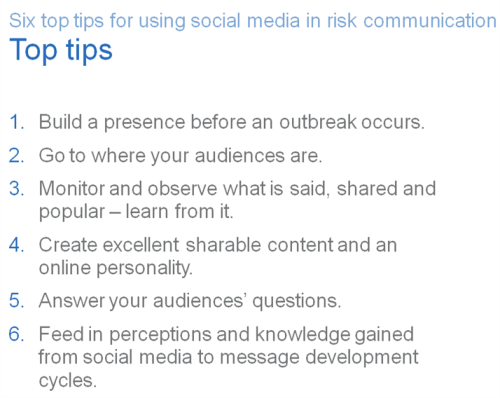

Whether or not social media is seen as a force for good or evil during pandemics, it is a communication channel that those seeking to protect public health cannot ignore. Nor can organisations and individuals involved in crisis communication be reactive to messages shared and posted in this competitive environment. They must instead take a proactive stance in establishing an authoritative presence on social media channels before and during a crisis.

At the recent TELL ME conference, Alexander Talbott, a digital communications consultant specialising in healthcare, offered the following guidance on realising this objective:

———————————————————————————————————————-

TELL ME (Transparent communication in Epidemics: Learning Lessons from experience, delivering effective Messages, providing Evidence) is a European Commission funded, collaborative project that has systematically reviewed existing evidence to develop practical guidance, online tools and models for improved risk and crisis communication during pandemics.

BMJ was the responsible partner for the report on New Social Media referenced above.