…in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

Finally I have come to address this topic, some months following publication of an eagerly awaited (at least by me) large clinical trial.[1] I have been a colleague and friend of the second author (ES-V) since proofreading her PhD thesis over 20 years ago. In those days I focussed solely on muscle so any suggestion of acupuncture being used to influence visceral function or blood flow was a bit of a conceptual stretch for me. After all my needles were going directly into the target that I wanted to influence, and I was just about comfortable with the idea that the needle alone actually did something useful without the need for injecting a drug. So the idea that acupuncture or electroacupuncture could have any useful effect through indirect influences only really arose when I read Lisa’s thesis.

Her early work stimulated interest in the use of acupuncture in fertility and augmented reproduction,[2,3] although the subsequent plume of clinical research that occurred in this field seemed to go a little off course from a basic science perspective, with an unwarranted focus on embryo transfer as part of IVF.[4] Lisa observed this, but continued with her research path, which was by then on PCOS. She clearly showed that segmental electroacupuncture (EA) could have positive influences on the condition, both in terms of hormonal and metabolic markers, and apparently in terms of ovulation rates.[5,6]

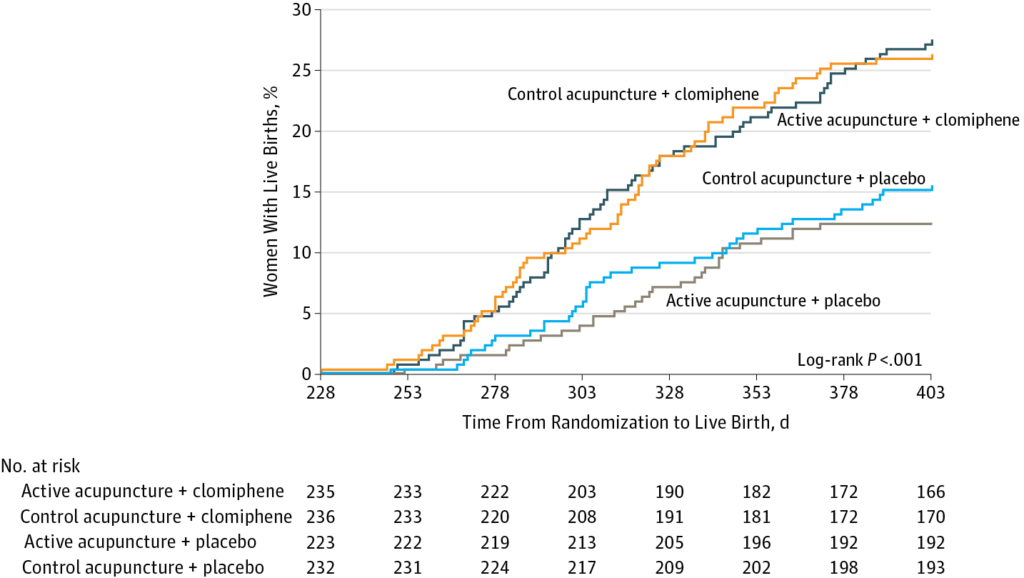

Lisa regularly runs research updates for the BMAS, and we were all excited to hear of her involvement in this huge clinical trial in China on women with PCOS. With 1000 women to be randomised and treated the trial was a considerable undertaking, and several years passed with no news. Then on the 27th June 2017 the results were out… clomiphene was nearly twice as good as segmental EA, and segmental EA was no better than a very minimal non-segmental sham.

It did not seem to make sense from the basic science perspective! The numbers were big enough to power the comparison with sham (assuming similar size effects to those we see in clinical trials of chronic pain). The intervention appeared sufficient in neurophysiological terms, to generate the effects that had been demonstrated in the basic science experiments that had led up to this trial. Yes it was a penetrating sham, but the physiological stimulus of the sham intervention would not have generated any effect in the laboratory in terms of somatovisceral reflexes. In the clinical realm, with conscious humans, sham always seems to have a substantial context effect, but still I would have expected some physiological effect from the segmental EA.

Well there was a difference between real and sham EA in terms of adverse events. In the segmental EA group the rate of diarrhoea was 3 times that in the sham EA group, perhaps indicating an excess effect in somatovisceral reflexes in a small proportion of women. It should be noted that the absolute rate of diarrhoea was low at 1.6 and 5%, in sham and real segmental EA respectively.

The primary outcome was live birth rate. This is the most valid outcome for trials of this nature, but it is not the same as ovulation induction of course, so it is not a direct measure of the putative physiological effect of segmental EA. This could add noise to the statistics, but even so, there was not even a trend in favour of segmental EA.

The slightly curious thing is that both acupuncture groups seemed to substantially outperform metformin, which, in a large comparative trial with clomiphene resulted in a live birth rate of just 7.2%.[7] The populations are not easily comparable though as there were notable differences in BMI that would favour acupuncture. The Chinese women were normal weight compared with an average BMI of about 35 in the metformin group in the prior comparative trial, and BMI is inversely related to outcome.[8] Could that explain the difference between 7.2 and 15.4%? Well frankly, I’m afraid it probably can!

So where does that leave the acupuncture in the fertility arena? There is little or no high quality clinical data to support its use, just a lot of experimental data that did seem encouraging, although the results of this trial should give pause to the assumptions of advocates that anything demonstrated at the bench should automatically imply useful effects at the bedside. For now at least we must encourage women with PCOS to consider clomiphene before acupuncture for ovulation induction.

References

- Wu X-K, Stener-Victorin E, Kuang H-Y, et al. Effect of Acupuncture and Clomiphene in Chinese Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. JAMA 2017;317:2502. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7217

- Stener-Victorin E, Waldenström U, Andersson SA, et al. Reduction of blood flow impedance in the uterine arteries of infertile women with electro-acupuncture. Hum Reprod 1996;11:1314–7.

- Stener-Victorin E. Reproductive medicine: Research projects in acupuncture. Acupunct Med 1998;16:80–2.http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/aim.16.2.80

- Carr D. Somatosensory stimulation and assisted reproduction. Acupunct Med 2015;33:2–6. doi:10.1136/acupmed-2014-010739

- Stener-Victorin E, Maliqueo M, Soligo M, et al. Changes in HbA1c and circulating and adipose tissue androgen levels in overweight-obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome in response to electroacupuncture. Obes Sci Pract 2016;2:426–35. doi:10.1002/osp4.78

- Johansson J, Redman L, Veldhuis PP, et al. Acupuncture for ovulation induction in polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2013;304:E934-43. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00039.2013

- Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD, et al. Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2007;356:551–66. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa063971

- Legro RS, Zhang H, Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Reproductive Medicine Network. Letrozole or clomiphene for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1463–4. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1409550

Declaration of interests

I am the salaried medical director of the British Medical Acupuncture Society (BMAS), a membership organisation and charity established to stimulate and promote the use and scientific understanding of acupuncture as part of the practice of medicine for the public benefit.

I am an associate editor for Acupuncture in Medicine.

I have a very modest private income from lecturing outside the UK, royalties from textbooks and a partnership teaching veterinary surgeons in Western veterinary acupuncture. I have no private income from clinical practice in acupuncture. My income is not directly affected by whether or not I recommend the intervention to patients or colleagues, or by whether or not it is recommended in national guidelines.

I have not chaired any NICE guideline development group with undeclared private income directly associated with the interventions under discussion. I have participated in a NICE GDG as an expert advisor discussing acupuncture.

I have used Western medical acupuncture in clinical practice following a chance observation as a medical officer in the Royal Air Force in 1989. My opinions are formed by data that spans the range of quality and reliability, much of which is in the public domain.

I have a logical mistrust of the motives of anyone who advertises an interest or hobby in being a ‘Skeptic’, as opposed to using appropriate scepticism within their primary profession, or indeed organisations that claim to promote generic ‘science’ as opposed to actually engaging in it.