The people living in Moria, a refugee camp in Greece, have been abandoned by Europe and treated like criminals for nothing more than wanting to be safe

I’ve done many assignments providing mental health services to people around the world. In Sierra Leone after Ebola, I worked with the survivors and those who had lost those closest to them to the deadly virus. People were affected by what had happened, but they were resilient. Neighbours and families cared for each other. They’d lost family, friends, and often their homes, but they didn’t lose their social structures, which meant that they could deal with their traumas.

I’ve done many assignments providing mental health services to people around the world. In Sierra Leone after Ebola, I worked with the survivors and those who had lost those closest to them to the deadly virus. People were affected by what had happened, but they were resilient. Neighbours and families cared for each other. They’d lost family, friends, and often their homes, but they didn’t lose their social structures, which meant that they could deal with their traumas.

In Lebanon, I treated patients who had lived through and escaped the horrors of the Syrian conflict. The refugee camp they lived in was very basic—with barely any electricity or decent water—but there was a structure. It didn’t look like a jail and people had their needs met.

Mosul earlier this year was really terrible—until now it was the worst I had ever seen. The people I met had fled for their lives from IS and the battle to retake the city. They were traumatised by what they had seen and experienced. But when they arrived at the MSF trauma centre they felt safe. They were happy; they had survived and weren’t scared for their lives anymore, which meant that they responded well to psychological support.

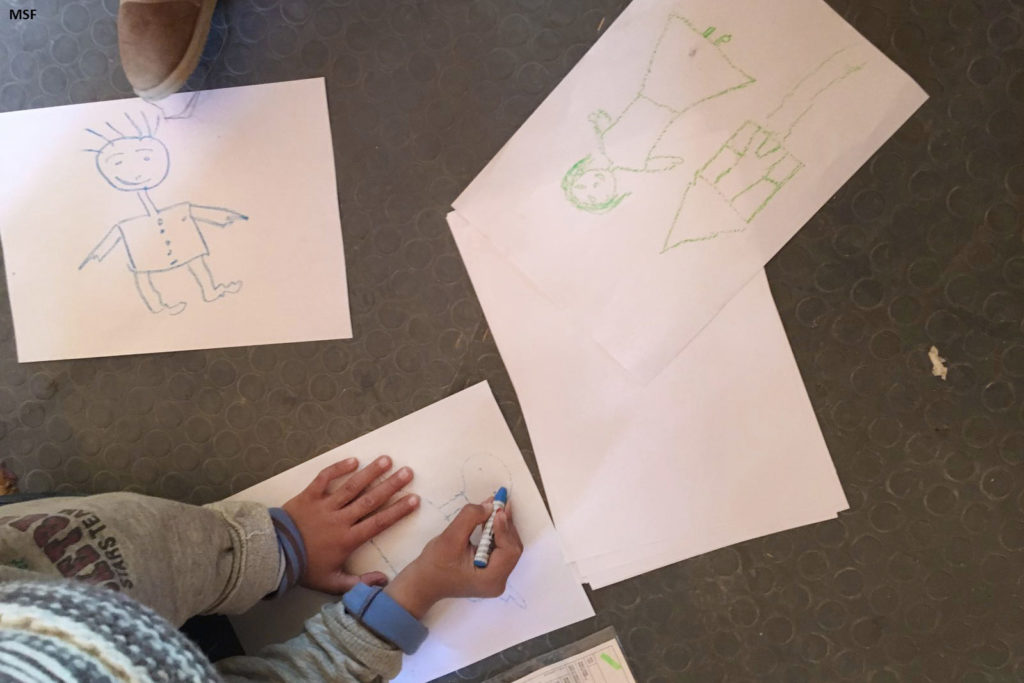

People really don’t need a lot to normalise and find stability. If they feel safe and can begin to organise themselves and arrange activities then they can cope and begin to rebuild their lives—even if it is in a camp. But the foundation that people need to be able to do that is completely missing in Moria, a refugee camp in Greece.

Moria is chaos. A former military base on the Greek island of Lesbos, it was built to temporarily house approximately 2000 people in 2015, but now holds close to 7000 people crammed in between its barbed wire fences; fences that you’d expect to see surrounding a high security prison. The population is predominantly Syrian and Iraqi, with two thirds of its inhabitants women and children.

There is a feeling among the people trapped there that you have to fight for many things to survive: clean water, decent shelter, warm clothes. People felt safer outside Mosul than they do here; the fences, the police, the anxiety of not knowing what will happen to them, it’s all too much. Men, women, and children live in fear every day of being sexually assaulted, exposed to violence, or being deported. Access to legal aid is scarce and the only place people can receive psychological support is our mental health clinic 5km away.

Truthfully, I have never seen anything as bad as this. “Yellow cases,” such as historic rape victims experiencing trauma from their attack, would be a priority in Austria. But here the waiting list is so long and the needs are so great that these people stand almost no chance of receiving psychological treatment, as the number of “red cases”—victims of torture, recent victims of sexual violence, and those at risk of suicide or self-harm—is so high.

The people who make it to Moria have often escaped unimaginable suffering and survived long, dangerous journeys to get there. They arrive full of hope at finally being in Europe. Then they find themselves stranded in an overcrowded camp where living conditions are inhuman and with no clarity on what will happen to them or if they will ever leave.

What makes it so hard for me is that all of this is preventable. Moria has been intentionally neglected by European governments in the hope that it will act as a deterrent to others considering making the journey to Europe. But in this intention, it has failed. It hasn’t stopped the 100 people who, based on Novembers figures, arrive on the islands each day. Europe has grossly underestimated how desperate people are.

Perhaps the only positive aspect of Moria, if I am forced to find one, is that because it is so crowded, those attempting suicide have no place or privacy to do it. People are stopped from harming themselves by others walking by or by those who sleep next to them. For example, there was a young Syrian man* who tried to hang himself outside the container he slept in. He was brought to the MSF mental health clinic by an older Somali man who stopped him. Now they come to all of his appointments together and he ensures that the young Syrian takes his medicine.

Then there is a man from Syria, Hassan, who lost his sons in the war. He shares a tent with a younger man with mental health problems from Iraq who was so lost in the camp that he never really knew where he was. Our team asked Hassan if he would make sure that the young man took his medication. Now, he comes every week to collect the medication for him. Hassan, who has suffered so much himself, now cares for him like a son and, in truth, we rely on him.

It’s this sort of humanity that gives me a little bit of hope for the people here who have been abandoned by Europe and treated like criminals for nothing more than wanting to be safe.

But this humanity can only go so far—just like the support that we provide. It’s not a permanent solution and, indeed, the only thing that can really relieve the terrible conditions inside the camp is for people to be moved off the island and on to mainland Europe. At the moment, the appalling conditions are exacerbating peoples’ health problems and stress levels. The lack of stability, quiet, routine, and proper treatment keeps people in a constant state of anxiety. Until this cycle ends, people will continue to be broken by Europe’s cruel deterrent tactics.

*The patients mentioned in these two paragraphs have had their names and nationalities changed, but they are representative of the patients that the team on Lesbos treat.

Monika Gattinger is a psychologist and psychotherapist who worked for 40 years in Austria before joining MSF in her retirement.

Competing interests: None declared.

Please support The BMJ‘s Christmas 2017 appeal for Médecins Sans Frontières, bringing medical volunteers to the world’s neediest people: donate at www.msf.org.uk/bmj

£123 could pay for a blood transfusion for three people

£65 could buy a stretcher to help move an injured person to safety

£54 could provide antibiotics to treat 40 war wounded people

Donate online: www.msf.org.uk/bmj

Donate by phone: 0800 408 3897 (UK only)