Even if we officially change the names of “GPs” and “junior doctors,” this will not address the underlying problem

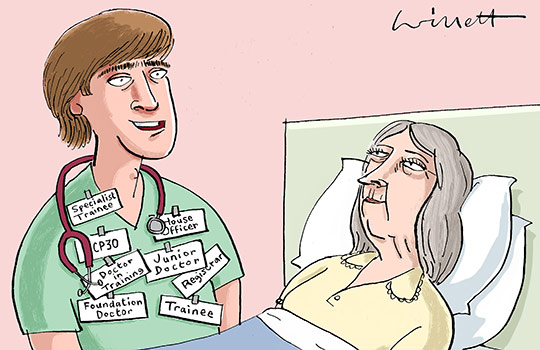

“SHO, let it go!” This is the slogan used in one of my workplaces, and variations of it will be familiar to most doctors in the NHS. It is meant to discourage trainees from using the term senior house officer (SHO) because the NHS moved away from this term years ago. It was hoped that this would help to differentiate core trainees from foundation year 2 doctors, and enable doctors to be recognised for their proper rank in the workplace. Newer campaigns have proposed terminology changes that would serve a similar purpose. Recently, England’s chief medical officer called for the term “junior doctors” to be replaced so trainees get the “respect they deserve.” Similarly, for years general practitioners have been calling for a title that better reflects their seniority, such as “primary care consultants.”

Does this really matter? How would these proposed changes positively impact on teamwork and patient care? As an analogy, am I undermining a consultant surgeon if I call him “Mr” rather than “Dr”? Or does it mean I am discrediting my colleague’s years of training if I call him by his first name rather than his title?

“Hello, this is Dr John Smith, MBChB, PhD, intercalated BSc, MRCP, ST5 on the phone.” What purpose does that serve, other than adding comic relief to the conversation?

The real problem is not your title: it is how your colleagues do not try to understand your abilities. Indeed, I have encountered instances where senior doctors do not even bother to learn the names of their juniors.

Too often the prejudice persists that junior doctors cannot contribute much to a healthcare team. Yet it is these team members who often have fresh knowledge from medical school. And even among new graduates, some may have had experiences in the past that are useful for medicine. For example, I know a medical colleague who used to work as a police officer who can tell me the services available for domestic violence victims.

Despite being very junior in their medical careers, new graduates are all valuable members of the team and should be treated as such. I understand that some senior trainees can feel uncomfortable being assimilated with the new graduates, and why they would therefore advocate for the name changing of “SHOs” and “junior doctors.” Yet all this achieves is to undermine the new graduates by the implication that they are inferior to the senior trainees.

The NHS work culture focuses too much on hierarchy and all too often it shows. When a junior doctor refers a patient to a senior colleague in another team, the senior’s first question is not always about the patient, but instead “what is your grade?” Once at work, a surgical consultant laughed about how a surgical registrar needed advice from an anaesthetics core trainee on the preoperative management of a patient. I do not see the humour in this case, as I think that anaesthetists are probably one of the most expert sources of knowledge in preoperative management. Even if this core trainee had then struggled with the registrar’s queries, they would still be the best person to escalate to seniors in the anaesthesia team.

Sadly, some NHS users have a similar mentality—they want to be directly managed by consultants, and refuse to be the “guinea pigs” of the junior doctors and medical students, who are under supervision of their seniors. It is hard to imagine how junior doctors could ever advance their skills if they are denied hands-on experience. These doctors would end up lacking confidence and competency in various high risk procedures, as well as the skill of critical decision making, when they become senior consultants.

I understand that the point of these proposed name changes is to improve trainees’ self-esteem. However, even if we officially change the names of “GPs” and “junior doctors,” someone will still inadvertently use these terms, as has happened with the term SHO.

Recently, the BMA and the Scottish government agreed a new contract, which will establish GPs as “expert medical generalists.” However, this move was not simply a name change, but an opportunity for GPs to lead expanded community multidisciplinary teams.

The underlying problem is not the name itself: it is people’s preoccupation with hierarchy, their failure to grasp teamwork, a lack of mutual respect, and prejudice of other team members’ abilities. In a truly patient centred model we—juniors and consultants alike—would all see ourselves as “public servants for patients’ health.”

Eugene YH Yeung has worked as a pharmacist, researcher, and medical doctor in Canada and the UK.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the

following interests: None.

References

- Baddeley R. A junior doctor by any other name. BMJ 2017;359:j4797.

- Wass V, Gregory S. Not ‘just’ a GP: a call for action. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(657):148-149.

- Yeung EYH. How are junior doctors supposed to learn without the opportunity? BMJ 2017;359:j5057.

- Christie B. Scottish GPs back new contract making them “expert medical generalists”. BMJ 2017;359:j5626.