One can hardly pick up a newspaper or magazine these days without reading something about artificial intelligence, typically in relation to computer programmes or robots.

One can hardly pick up a newspaper or magazine these days without reading something about artificial intelligence, typically in relation to computer programmes or robots.

In March 2017 a computer programme, AlphaGo, beat a world champion, the South Korean Lee Sedol (pictured below), at go, a game once thought to be too difficult for computers to master at that level. It had already beaten the less highly regarded European champion, Fan Hui, in October 2016. AlphaGo relies on neural networks, a database of many millions of games, Monte Carlo techniques, and programmed learning. A new computer programme, AlphaGo Zero, using no database, fewer training games, and reinforced learning, recently beat AlphaGo 100–0.

The first method for programming a computer to play chess was described by Claude Shannon in 1949. With great foresight he suggested that a chess playing programme “should make more use of brutal calculation than humans.” Early programming attempts concentrated on mimicking human play, but when more powerful computers became available, it became clear that brute force was superior. In 1997, a computer, Deep Blue, defeated the then world champion, Garry Kasparov (pictured below). This year Kasparov, having finally come to terms with that loss, wrote a book, Deep Thinking, describing the event and the implications for the development of computer intelligence.

Surprisingly, a computer has never defeated a reigning world champion at draughts (checkers), a computationally simpler game. In 1994 the Chinook programme might have beaten the then world champion, Marion Tinsley, who withdrew after six drawn games and died a week later from pancreatic cancer; the programme then beat the second ranked player, Don Lafferty. It has since been shown that, with perfect play, games of draughts are always destined to be drawn.

These programmes play games that are undoubtedly difficult, but whose parameters are strictly bounded. Perhaps more impressive is Watson, a computer programmed to answer questions posed in natural language, by scrutinising hundreds of language analysis algorithms simultaneously. In 2011 Watson beat two former winners of the US television quiz game Jeopardy (pictured below). It has since been put to use in diagnosis and drug discovery.

Natural language processing (NLP) concerns the ways in which computers deal with natural languages. Watson is one manifestation, and machine translation, still somewhat rudimentary but improving, is another. Detailed case histories can be analysed in prevention, diagnosis, and management of adverse drug reactions, using techniques such as automated text analysis and data-driven cluster analysis, although the potential is not yet fully realised in pharmacovigilance.

It is unsurprising that the task of reading a text can be accomplished by artificial intelligence, since “intelligence” has reading at its core. The Latin word intellegere comes from inter, among or between, and legere, to gather or collect, to pick out or choose, and to read or learn by reading. It therefore implies reading between the lines, and therefore means to understand by inference, to deduce, infer, discern, recognise, and appreciate, or to comprehend the meaning of language.

Legere comes from the IndoEuropean root LEG, to gather, set in order, choose, read, or speak. You read a lecture or a lesson at a lectern, perhaps eclectically, if your notes are legible and you don’t have dyslexia. In Greek λόγος is a word or discourse. Most words ending in –ology mean studies of one sort or another, but in some cases the suffix means literally a word; for example, haplology, a process of contraction whereby a single letter or syllable results instead of two that are identical or sound similar; mineralogy and mammalogy are examples of haplology—they would have been mineralology and mammalology, had contraction not occurred. Dittology is ambiguity in reading or interpretation. An apology was originally a speech in defence. Doxology is speaking praise to God. Trilogies and tetralogies are sets of three or four books. Then there are prologues, epilogues, and the Decalogue, 10 important sets of words.

“Intelligence” entered English in the late 14th century, meaning the faculty of understanding and a capacity to understand. It soon came to mean sagacity, understanding, comprehension, knowledge, and hence, in the late 15th century, a piece of information or news.

We have known since the 1950s that computerised medical algorithms, created (don’t forget) by human intelligence, can perform as well as humans, or better. Artificial may mean fake and intelligence means news, but artificial intelligence is by no means fake news.

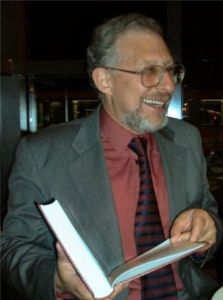

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.