By Richard Smith and David Pencheon

By Richard Smith and David Pencheon

In 2007 Fiona Godlee, editor of The BMJ and somebody who has been concerned about the environment for at least 30 years, was outed as a “climate criminal” for flying too much. We too are concerned about the environment, but we both have cars, washing machines, dishwashers, and tumble driers and five children between us (RS three, DP two). DP has a second home courtesy of his wife, but never flies and does not eat meat. RS, in contrast, eats meat and flies tens of thousands of miles every year. Why are people who are very worried about the world in which their children and grandchildren will have to live so cavalier in their attempts to reduce their carbon and wider ecological footprint?

Psychoanalyst Sally Weintrobe has an answer: disavowal. We are all familiar with the concept of denial whereby our minds simply erase a terrible threat. Doctors see it commonly in people with a cancer that will kill them. The late Aidan Halligan cited it as the human emotion (greater than love, lust, or lucre) that most dictated our individual and collective behaviours. But few people deny the existence of climate change: the person on the Clapham omnibus knows that it’s happening.

Disavowal, says Weintrobe, is “a state where we’re aware of something very important [for example, climate change and its effects,] but ‘find ways to remain undisturbed’ by the implications of it, rather than being stirred into action.” Disavowal is artful and protean. We minimise the risk, put it to the back of our mind, forward it to the future, or convince ourselves that there will be a technical solution.

We think the plane will go whether or not we are on it. We recognise the fallacy of the argument, but our capacity to disavow means we depart on the plane. Or we may, says Weintrobe, adopt a “Noah’s Ark mentality,” thinking that we and our family will survive while most will die. The American physicist Fred Singer imagined Noah surrounded by “complacent compatriots” saying, “Don’t worry about the rising waters, Noah, our advanced technology will surely discover a substitute for breathing.”

Another aid to disavowal is to reflect that since the first stories were told people have been imagining the end of the world in various forms. In our lifetimes there has been destruction by nuclear weapons, nuclear winter, and currently takeover by machines. None of these threats has ever materialised, helping us disavow and be sure climate change won’t make life intolerable.

Perhaps another related mental strategy for avoiding the actions we should be taking is “compartmentalisation,” which allows us to separate one part of our mind completely from another—the process that allowed Bill Clinton to have oral sex in the Oval Office while talking on the phone to foreign presidents. Sometimes we think about the terrible effects climate change is likely to have, but mostly we don’t.

Another factor is that people know about the risk of climate change but fail to understand the size of the risk. This is true for smokers, where the risk is well established. Most people know that smoking (and climate change) is very risky, but few of us know how risky—certainly not in terms that have an emotional and behavioural impact. For the record, those of us who smoke 20 cigarettes a day face a 50:50 chance of dying early because of the habit—Russian roulette with three bullets in a six chamber revolver. The scale of the risk of climate change is similarly huge, but cannot be framed anything like as precisely, making disavowal easy.

And although there is no uncertainty over whether climate change is happening and that it’s the result of human activity, there remains uncertainty over what the exact effects will be. These effects are already happening and will, we know, be severe, but our minds latch onto the uncertainty and allow it to crowd out the certainty. Our willingness (almost desperation) to cling onto uncertainty has been skilfully and dangerously exploited by many sectors: from tobacco to fossil fuel companies.

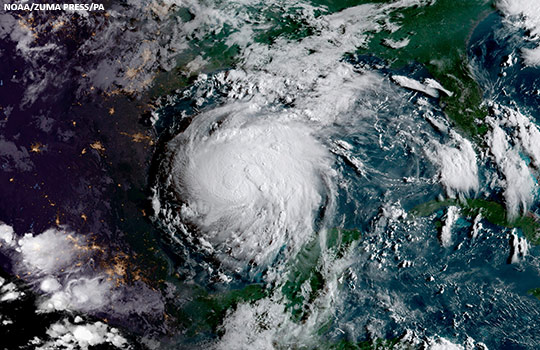

Similarly, we know that the number and severity of extreme weather events is increasing, but we cannot be certain whether any particular event is caused directly by climate change. Disavowal feeds off uncertainty, and with the complexity of global weather systems there will always be uncertainty. Scientists, unfortunately, help our disavowal because they live every day with uncertainty and correctly are reluctant to offer the unqualified statements that policy makers and the public find more convincing

The media facilitate disavowal by feeling it necessary “for the sake of balance” to include a climate change denier in every discussion of climate change. Naomi Oreskes puts it this way in her classic book Merchants of Doubt: “While the idea of equal time for opposing opinions makes sense in a two-party political system, it does not work for science, because science is not about opinion. It is about evidence.”

Governments, says Weintrobe, also disavow. They set targets and then fail to meet them. It’s akin to the medical student worried about a biochemistry exam who rushes out, buys a textbook of biochemistry, puts it on a shelf, and then sleeps contentedly. Governments confuse talking and action.

But does recognising disavowal help us? Once you recognise your capacity to disavow you’ll find it everywhere, which is helpful in the ultimately impossible task of fully understanding yourself. Yet recognising the tricks your mind plays does not allow you to avoid them. Although Daniel Kahneman has categorised the cognitive tricks and biases of the mind in the marvellous book Thinking Fast and Slow, he’s clear that he cannot avoid them in himself.

“Humankind,” writes T S Eliot, “cannot bear very much reality.” Our capacity to deny, disavow, and compartmentalise are mental functions that allow us to get up every morning and keep going no matter how many awful things happen to us and others. In that sense they have been evolutionary useful, but we now face problems beyond anything that we as a species have experienced before. “We are,” as President Obama said, “the first generation to feel the effect of climate change and the last generation who can do something about it.” And mental functions that have until now protected may now condemn us.

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.

Competing interest: None declared.

David Pencheon is a UK trained doctor and is currently director of the Sustainable Development Unit (SDU) for NHS England and Public Health England.

Competing interests: No competing interests to declare.