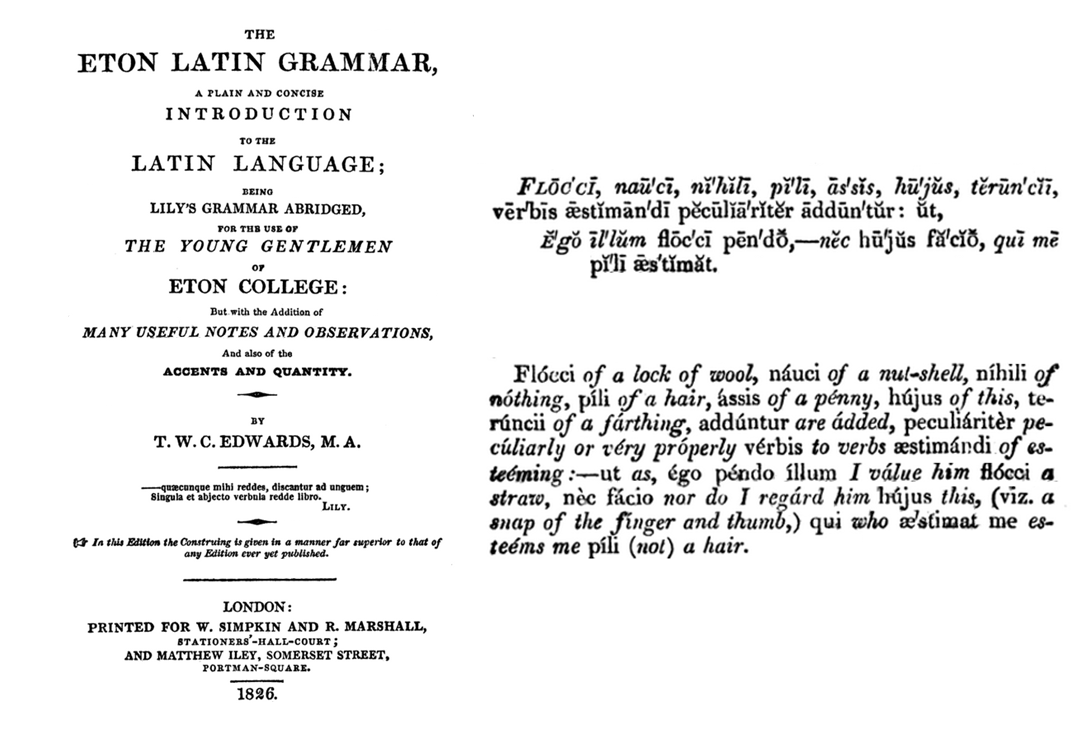

Earlier this week, the media delightedly reported that Jacob Rees-Moggs had referred to floccinaucinihilipilification in a parliamentary speech. It comes from Latin: floccus, a wisp of wool, naucum, a trifle, nihil, nothing, and pilus, a hair, words that belittle whatever they are referring to. The word is not new. The Oxford English Dictionary finds it first recorded in 1741 and defines it as “the action or habit of estimating as worthless”. The meanings of the separate elements were glossed in the Eton Latin Grammar (1826; picture). But it is not the longest word in the English language, as anyone with pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism will attest.

Earlier this week, the media delightedly reported that Jacob Rees-Moggs had referred to floccinaucinihilipilification in a parliamentary speech. It comes from Latin: floccus, a wisp of wool, naucum, a trifle, nihil, nothing, and pilus, a hair, words that belittle whatever they are referring to. The word is not new. The Oxford English Dictionary finds it first recorded in 1741 and defines it as “the action or habit of estimating as worthless”. The meanings of the separate elements were glossed in the Eton Latin Grammar (1826; picture). But it is not the longest word in the English language, as anyone with pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism will attest.

The title page (left) and extracts (right) from The Eton Latin Grammar of 1826 by T W C Edwards, dedicated to “The Reverend John Keate, DD, Head Master of Eton College”. It was originally created by combining three early 16th century treatises by William Lily (1469–1522), the first high master of St Paul’s School, London; the resulting work was known as Lily’s Grammar, and it was used in schools by order of Edward VI. It was revised in the 18th century as the Eton Latin Grammar, which became the standard Latin textbook for schoolboys in the 19th century. The gloss suggests that floccinaucinihilipilification should mean not giving a toss for one who has no regard for me.

What the longest English word is depends on what you mean by a word. For example, the polypeptide enzyme tryptophan synthetase has a name, 1913 letters long, consisting of the string of terms used to describe each of its 267 constituent amino acids, starting methionylglutaminylarginyl- and ending -threonylarginylserine. But that’s hardly a word.

In Headlong Hall by Thomas Love Peacock (1816), Mr Cranium uses a 51 letter “word” to describe the constituents of the human body: “Ardently desirous, to the extent of my feeble capacity, of disseminating as much as possible, the inexhaustible treasures to which this golden key admits the humblest votary of philosophical truth, I invite you, when you have sufficiently restored, replenished, refreshed, and exhilarated that osteosarchaematosplanchnochondroneuromuelous, or to employ a more intelligible term, osseocarnisanguineoviscericartilaginonervomedullary, compages, or shell, the body, which at once envelopes and developes that mysterious and inestimable kernel, the desiderative, determinative, ratiocinative, imaginative, inquisitive, appetitive, comparative, reminiscent, congeries of ideas and notions, simple and compound, comprised in the comprehensive denomination of mind, to take a peep with me into the mechanical arcana of the anatomico-metaphysical universe.” Quite so.

Then there’s the English transliteration (182 letters) of the gargantuan Greek word of 170 letters used by Aristophanes in his play The Ecclesiazusae to describe “a dish compounded of all kinds of dainties, fish, flesh, fowl, and sauces”, as it is described in Liddell & Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon: λοπᾰδο-τεμᾰχο-σελᾰχο-γᾰλεο-κρᾱνιο-λειψᾰνο-δρῑμ-ῠποτριμμᾰτο-σιλφῐο-κᾱρᾰβο-μελῐτο-κᾰτᾰκεχῠμενο-κιχλ-επῐκοσσῠφο-φαττο-περιστερ-ᾰλεκτρῠον-οπτο-κεφαλλιο-κιγκλο-πελειο-λᾰγῳο-σῐραιο-βᾰφη-τρᾰγᾰνο-πτερύγων, or lopado-temacho-selacho-galeo-kranio-leipsano-drim-hypotrimmato-silphio-karabo-melito-katakechumeno-kichl-epikossupho-phatto-perister-alektruon-opto-kephallio-kinklo-peleio-lagoio-siraio-baphē-tragano-pterygōn. [Note: κιγκλο is often transliterated kigklo, but γκ in Greek was pronounced nk.] This delicacy contains shark, dogfish, crayfish, thrush, blackbird, ringdove, pigeon, cock, mullet, wagtail, rockdove, and hare, basted in a pungent sauce of silphium, honey, and mulled red wine.

Many other words have been touted as being the longest, such as the 10 “thunderclaps” in Finnegans Wake, each 100 or, in one case, 101 letters long. However, the longest word listed as a lemma in the Oxford English Dictionary is a medical one: pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis. When Greek athletes contested in the nude they oiled their bodies. Wrestlers then applied κονία (konia), a fine dust that gave them a better grip on each other. So a coniosis, such as pneumoconiosis, is a disease caused by dust. In this case, the dust is deposited in the lungs (πνεύμωνα, pneumōna), is very fine (ultramicroscopic), and is derived from volcanic silica.

However, this turns out to be illusory; the OED says that it is “a factitious word alleged to mean ‘a lung disease caused by the inhalation of very fine silica dust’ but occurring chiefly as an instance of a very long word.” It was coined in 1935, supposedly by Everett M Smith, the then president of the National Puzzlers’ League. Nevertheless, when a group of Indonesian doctors described a form of anthracosilicosis in a 35 year old man who had been exposed to ash for about 10 months during a prolonged eruption of the Merapi volcano in Central Java, which they could simply have called silicovolcanoconiosis, they preferred instead to use the longer word, which now therefore seems to describe a real entity. Some words that were invented simply for the purpose of coining a word or as nonsense words have entered the language (“quiz” is a supposed example), but it is unusual for one so coined to have been later reified.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.