Does being a doctor mean that you’re obliged to believe in progress? Richard Smith discusses

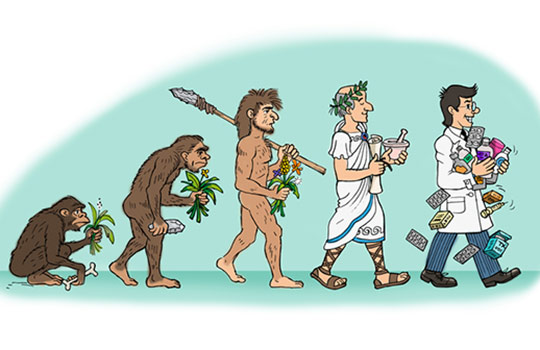

“All of these young men,” writes Victor Hugo in Les Misérables, “so diverse but who, when all is said, deserved to be taken seriously, had a religion in common: Progress.” As I read this, I wondered whether as a doctor, perhaps simply as a citizen in 2017, you are obliged to believe in progress just as previous generations were obliged to believe in God or face being burnt by the Inquisition or refused admittance to English universities.

“All of these young men,” writes Victor Hugo in Les Misérables, “so diverse but who, when all is said, deserved to be taken seriously, had a religion in common: Progress.” As I read this, I wondered whether as a doctor, perhaps simply as a citizen in 2017, you are obliged to believe in progress just as previous generations were obliged to believe in God or face being burnt by the Inquisition or refused admittance to English universities.

I’m not sure whether Hugo himself believed in progress, but I suspect not. Les Misérables is set mostly in the years after Napoleon, and Hugo seems both to regret the snuffing out of the freedom, spirit, and fervour of the French Revolution and the grandeur and brilliance of Napoleon, but also to think that they will return. But by calling progress a religion, something you must accept on faith, and giving it a capital P he seems to be sceptical of the notion.

But isn’t to be a doctor to be obliged to believe in progress? What is the point of all the billions spent on medical research if not to cure presently incurable diseases, relieve suffering, push back death, and extend life? Cancer, like dementia, motor neurone disease, schizophrenia, impotence, infertility, and depression will be cured. Babies born at 20 weeks, and then 15 weeks, will be kept alive without disability. Diseases will be eradicated and prevented. Public health will improve. The NHS will reach a stable state, responding to everybody’s needs, providing fulfilling but not excessively demanding employment, and balancing its budget without strain.

The Sustainable Development Goals are an embodiment of the religion of Progress; its Ten Commandments. Preventable deaths will not occur. Poverty will disappear. All children will be educated. We in rich countries will live as well as now if not better, and the other six billion people will live as well as we do now but all in a way that will put no strain on the planet. There will be universal healthcare coverage.

The very existence of medical journals like The BMJ and Lancet implies a belief in progress. They may contain accounts of failure, particularly by the government and other authorities, but they are full of ideas on how to do better, to progress. Medical schools are training future generations of doctors with the clear message that they will be better—sharing decisions with patients, knowing genetics, comfortable with information technology, better at communicating, more multidisciplinary, more compassionate, and superior in all ways to what has gone before.

Politicians more than anybody must believe in progress and sing it from the rooftops in order to garner votes and be elected. My political party, “Life is Tough, We Have No Solutions,” has not flourished, and every politician must promise a better tomorrow. Brexit may prove to be a catastrophic decision for Britain, but we must believe that Global Britain will be a place more magnificent than the Britain of the first Queen Elizabeth or Britain with an empire on which the sun never set. We will not return to a time comparable to when Britain was filled with cold, wet, illiterate, naked, warmongering savages while the Greeks were inventing philosophy and democracy.

As a doctor you can be aware of deficiencies, critical of present circumstances, and sceptical about proposed reforms, but ultimately you must believe in progress. I realised this clearly when I took part in a debate on whether the future will be healthier. I was cast as the pessimist and may have overstated my case. The optimist made his case well, but the three supposedly neutral witnesses were all wildly optimistic. I realised that they had to be, no matter what they may have thought privately. One was the chair of the council of the Royal College of General Practitioners, one deputy head of NHS England, and one public engagement director of the Hundred Thousand Genomes Project. You can’t hold such positions and not believe in progress.

To many people, progress is self-evident. Life expectancy is increasing across the world. We can travel into space. The human genome has been unravelled. Women have been liberated. The US has had a black president.

John Gray is the philosopher who is sceptical about progress. He concedes that science is progressive in that we steadily understand more and will not revert to suddenly understanding less. He would not concede, however, that the social and political consequences of science will be beneficial. It’s science that has allowed us to overheat the planet, build bombs that could wipe out the species, and create machines that might replace us. His argument is that if you look back at history, what seems like progress—like the growth of democracy or the liberation of women—can be rapidly reversed.

Progress is not inevitable and is a religion. But as a politician, doctor, research scientist, or public official you’d better believe.

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.

Competing interests: None declared.