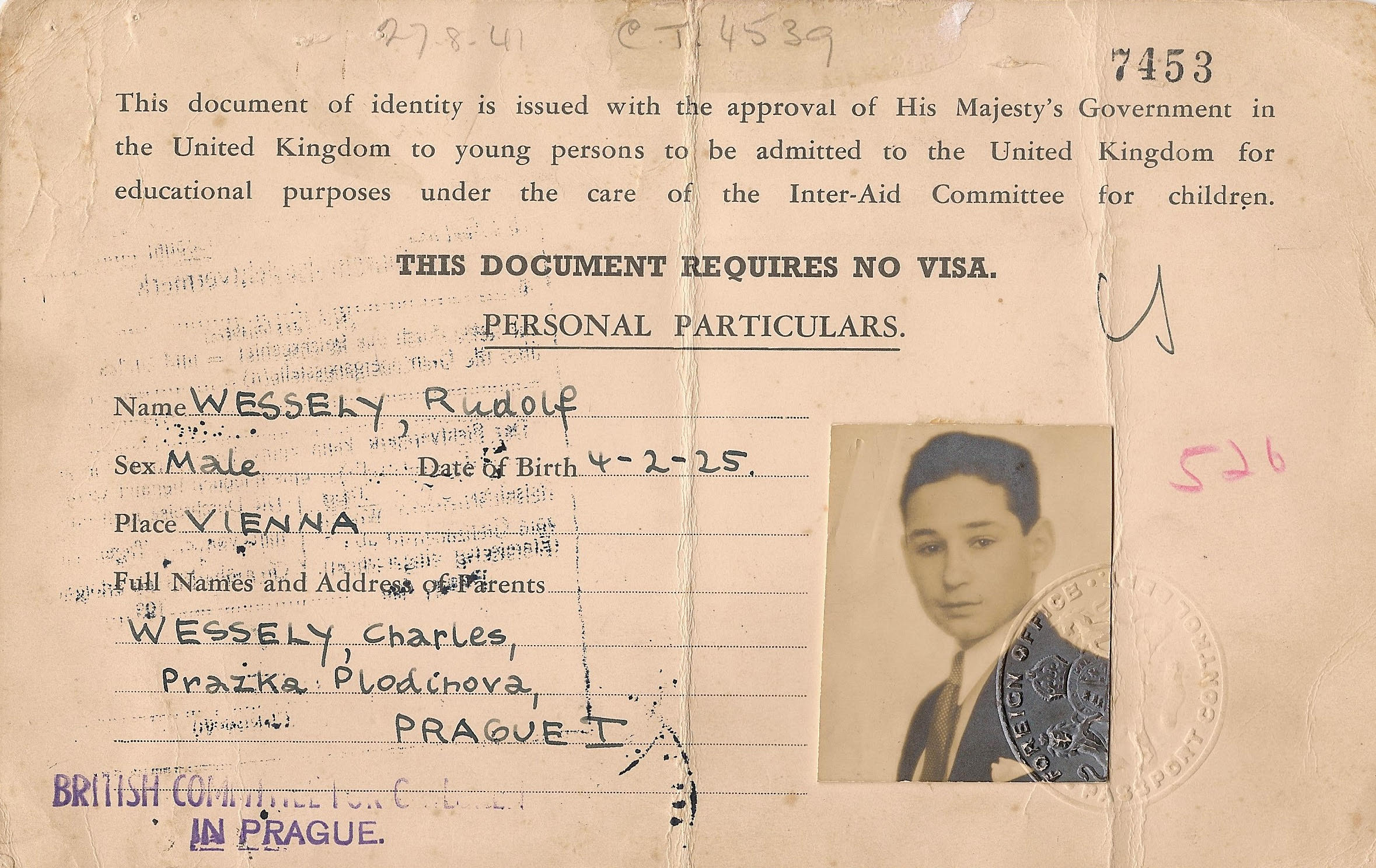

On Tuesday of this week I hosted a dinner at the Royal College of Psychiatrists for a group of medical students who are part of our “Pathfinders”—a scheme to give interested students some support and contacts to get them started in a career in psychiatry and especially psychiatry research. Also attending were other psychiatrists interested in the scheme, one of whom sat next to me. According to the placeholder his name was Dr Petr Schiller. In conversation I took a guess that his name was Czech, and so it proved. He told me that he had come to this country in the summer of 1939 as a small boy, on a train from Prague, arranged by a man called Nicky Winton. He was one of the 669 Jewish children who Nicky had rescued from what would prove to be certain death. That story would have held the attention of anyone, but it affected me more than most, as those sitting near us recognised. Because unknown to Petr there had been another child on the same train, a boy called Rudi Wessely. My father.

On Tuesday of this week I hosted a dinner at the Royal College of Psychiatrists for a group of medical students who are part of our “Pathfinders”—a scheme to give interested students some support and contacts to get them started in a career in psychiatry and especially psychiatry research. Also attending were other psychiatrists interested in the scheme, one of whom sat next to me. According to the placeholder his name was Dr Petr Schiller. In conversation I took a guess that his name was Czech, and so it proved. He told me that he had come to this country in the summer of 1939 as a small boy, on a train from Prague, arranged by a man called Nicky Winton. He was one of the 669 Jewish children who Nicky had rescued from what would prove to be certain death. That story would have held the attention of anyone, but it affected me more than most, as those sitting near us recognised. Because unknown to Petr there had been another child on the same train, a boy called Rudi Wessely. My father.

The Winton “children,” as they became known, were in the news again yesterday. This was because of a third child on the same train, a 6 year old boy called Alf Dubs. Alf and indeed Petr were among the luckier of the children on the train—both would be reunited with their parents in the UK. My father’s story was sadly much more typical. He would never see his parents again—they were both murdered at Auschwitz in September 1943.

I have often wondered what it was that made them decide to send their only child off into the unknown that day in the summer of 1939. Things were bad, but they could not have known the fate that would have befallen their son if he had stayed with them. As the shadows fell around them, did they ever gain at least some peace from knowing that their son would indeed be safe? It is good to note that some of the surviving Winton children are now raising funds for a memorial to the parents to be erected at the station where nearly all waved goodbye to their children for the last time.

Unlike my father, who was 13 at the time of the train, Alf doesn’t remember much of the trip. And, like all the Kindertransport survivors, he didn’t know the identity of the man who organised the rescue until much later. But Petr, my father Rudi, and Alf all had one thing in common. They all would do something in return for the act of charity and courage that had saved their lives.

Petr supports philanthropic causes—that’s how we met. My father did voluntary work for the Abbeyfield Society and joined the national committee, which is where he ended up sitting next to Nicky Winton, and a conversation ensued about my father’s accent. And, gradually, my father realised he was sitting next to the man who had saved his life. It was the first time since Liverpool St station in 1939 that Nicky had ever met one of the “children” he saved—another of those coincidences that even a Hollywood screenwriter would think twice before inventing.

What happened to Alf? He went into politics, became the Labour member for Battersea, and on his retirement joined the House of Lords. But he also never forgot his background, and I often saw him at the regular birthday celebrations for Nicky Winton that many of the “children” and their families attended at the Czech Embassy until the end of Nicky’s life—he died aged 105 last year. So as the Syrian refugee crisis deepened, Alf decided to do something, drawing on the legacy of the Kindertransports. Last year he introduced an amendment to the Immigration Bill, which would mandate the government to arrange to bring to the UK refugee children who had become trapped in Europe. Initially, he proposed 3500 children for the scheme, but later withdrew an exact figure. Instead, the government agreed to let in 400. But yesterday the government got into hot water when it seemed that they were stopping the scheme before it had reached even that modest target.

Theresa May is very familiar with the story of Nicky Winton. She was his MP and spoke movingly at his memorial service at the Guildhall last year. She, however, defended the government’s policy yesterday at a press conference with the Italian Premier, although critics from both sides of the House accused her of mixing up the larger general resettlement scheme for Syrian refugees with the specific targets of the Dubs Amendment, children separated from their parents outside Syria. The home secretary, Amber Rudd, later elaborated the decision by saying that child refugees were acting as magnets for people traffickers, although Yvette Cooper responded by saying that closing legal routes would encourage, not deter, people traffickers.

The government has been accused of back sliding, lacking compassion, acting out of self interest, failing to grasp the scale of the refugee crisis, and viewing it solely from a domestic parochial perspective. But this is nothing new. As Louise London has outlined, between 1933 and 1945 British policy towards Jewish refugees was always based on the politics of self interest, and subject to numerous caveats. There was a fear that it might fuel anti Semitism, that refugees would take “British” jobs (unless they were prepared to enter domestic service, where there was a shortage). Refugees were also expected to minimise their “foreignness,” and not become burdens on the state. The Methodist family in Hull who gave a home to my father had to pay a bond of £50 (about £2500 in today’s money) before he was granted a visa. Throughout the period, says London, British policy was intentionally vague, and always avoided any specific commitments or quotas.

Ultimately, Nicholas Winton did not alter the course of history, and neither would the amendment proposed by Alf Dubs, the child he saved in 1939. Historians agree that the British government was powerless to stop the genocide of the Jewish people in Europe, and the numbers that Winton saved were but a drop compared to the ocean of blood that was the Holocaust. Likewise, compared to the scale of the Syrian refugee crisis, even if the government were to lift the block they have now imposed, and returned to the original figure of 3500 isolated children, the Dubs amendment would barely dent the scale of the problem.

But that misses the point. Sitting in some squalid camp somewhere in Europe are children just like Rudi, Petr, and Alf. And if they came to this country, they too would be as grateful to our country as Rudi, Petr, and Alf were. And 50 years later, we would see another generation of former refugees giving back to society something of what they had received, by their own charitable and humanitarian activities.

And what about us? Why does the story of Nicky Winton and his children continue to move and inspire, and why did the Dubs Amendment touch the conscience of Parliament, and its rejection yesterday cause such anger? I think it is because against the background of darkness that had eclipsed most of Europe after 1939 or Syria now, those small beams of light shine even more brightly.

Simon Wessely is Regius chair of psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neurosciences, and president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Simon Wessely will be in conversation with Jim Al Khalili about this and much else for The Life Scientific, BBC R4 9.05 am, Tuesday 14 Feb.