I squirm every time I hear that “increasing patient demand” is driving up costs in the NHS. I squirm because demand, although a standard technical word of economists, sounds so pejorative and blaming. “Those bloody patients. If they’d only stop demanding so much the NHS would be fine.” It’s crucial to understand (but is not widely understood) that the main driver of costs in health care systems is the rising cost of medical interventions—the fact that much more can be done. This gives rise to what economists call “supply-led demand.” As one senior NHS leader once said to me, the main driver of costs in the American health system is the National Institutes of Health, the biggest funder of medical research in the US (and the world) because it keeps inventing stuff.

I squirm every time I hear that “increasing patient demand” is driving up costs in the NHS. I squirm because demand, although a standard technical word of economists, sounds so pejorative and blaming. “Those bloody patients. If they’d only stop demanding so much the NHS would be fine.” It’s crucial to understand (but is not widely understood) that the main driver of costs in health care systems is the rising cost of medical interventions—the fact that much more can be done. This gives rise to what economists call “supply-led demand.” As one senior NHS leader once said to me, the main driver of costs in the American health system is the National Institutes of Health, the biggest funder of medical research in the US (and the world) because it keeps inventing stuff.

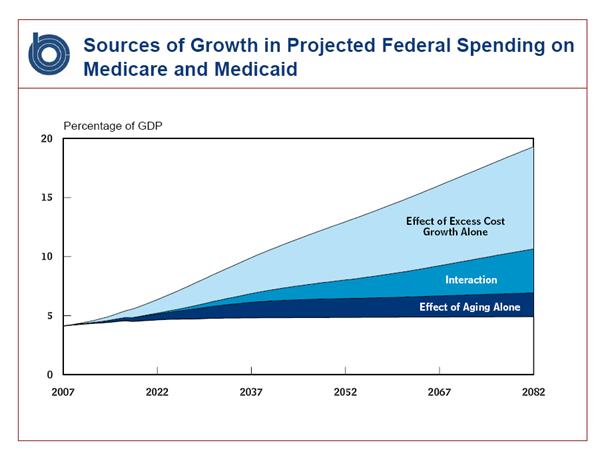

The Congressional Budget Office has looked at the drivers of increased spending on Medicare and Medicaid and concluded that aging of the population is a relatively minor factor and that most of the growth comes from increased health costs. Some of the increase comes from a combination of the two because older people are major consumers of the expensive health interventions.

Supply-led demand is the main driver of the high health costs in the US, and Jack Wennberg, “the father of variation studies,” points out that every doctor who graduates in the United States immediately creates lifetime medical costs of around $5-6m. More doctors, more hospitals, more intensive care units, more tests, more treatments means more cost. The extra cost would perhaps be justified if it produced high value, better outcomes—but usually it doesn’t. Think of the new expensive cancer drugs which produce only short periods of extra life often accompanied by more suffering in small numbers of people. Think of keeping ever smaller babies alive: some survive to live normal lives, but many are severely disabled—and the costs are huge. And even when there is small extra benefit the consequence of spending more on healthcare is that spending on education, housing, social care, the environment, and other things that can produce much more value (and even more health) are “crowded out,” as economists say.

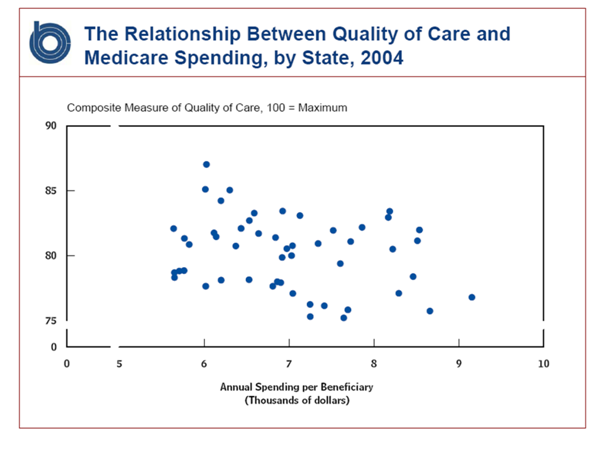

The US and UK health systems—indeed, every health system that has been studied—show wide variations in cost and quality, yet there is little or no relation between costs and quality. Indeed, as the figure shows there may be an inverse relationship—higher expenditure goes together with lower quality, perhaps because of the high costs of poor treatments that have to be followed by further treatment.

Recognising that the lack of a clear relationship between expenditure and quality is uncomfortable for doctors (and counterintuitive to most members of the public), Atul Gawande set out to try and put a human story to the statistics by visiting McAllen, a city on the US Mexico border which then had a spend for each Medicare enrollee of $15 000 a year—about twice the national average. He also made comparisons with El Paso, another city on the US Mexico Border, where the spend for each Medicare enrollee was $7500. Gawande established that it wasn’t different disease patterns, and El Paso had mostly better outcomes.

The explanation was in how medicine was practised in McAllen. He described a discussion with McAllen doctors at dinner:

“I gave the doctors around the table a scenario. A forty-year-old woman comes in with chest pain after a fight with her husband. An EKG is normal. The chest pain goes away. She has no family history of heart disease. What did McAllen doctors do fifteen years ago?

Send her home, they said. Maybe get a stress test to confirm that there’s no issue, but even that might be overkill.

And today? Today, the cardiologist said, she would get a stress test, an echocardiogram, a mobile Holter monitor, and maybe even a cardiac catheterization.

“Oh, she’s definitely getting a cath,” the internist said, laughing grimly.”

Doctors in Britain tend not to be as aggressive as those in the US, but perhaps the conversation in Britain would not be much different as we try to chase down every last risk, often ignoring the adverse effects of doing so.

Gawande then went to Wennberg’s centre in Dartmouth and got some statistics comparing medical practice in McAllen and El Paso:

“Between 2001 and 2005, critically ill Medicare patients received almost fifty per cent more specialist visits in McAllen than in El Paso, and were two-thirds more likely to see ten or more specialists in a six-month period. In 2005 and 2006, patients in McAllen received twenty per cent more abdominal ultrasounds, thirty per cent more bone-density studies, sixty per cent more stress tests with echocardiography, two hundred per cent more nerve-conduction studies to diagnose carpal-tunnel syndrome, and five hundred and fifty per cent more urine-flow studies to diagnose prostate troubles. They received one-fifth to two-thirds more gallbladder operations, knee replacements, breast biopsies, and bladder scopes. They also received two to three times as many pacemakers, implantable defibrillators, cardiac-bypass operations, carotid endarterectomies, and coronary-artery stents. And Medicare paid for five times as many home-nurse visits. The primary cause of McAllen’s extreme costs was, very simply, the across-the-board overuse of medicine.”

Doctors in the UK will, I fear, instinctively dismiss this as unique to America and nothing to do with the UK—just as we did with the America evidence on medical error until we finally did our own studies and found that the rates were the same. The US does have a bigger problem with supply-led demand, but it also has much better data on what’s happening in the health system and the cost. When we do studies here we find the same variations, the same lack of a clear relation between costs and quality, and evidence of unnecessary and futile care. Indeed, it was a British researcher who first showed variation.

I think of this in relation to the NHS in Dumfries and Galloway which I have visited repeatedly since 1980. When I first visited people could remember the 1940s when there were no surgeons and only two physicians. Now there are dozens of surgeons and physicians, most of them specialists. The health service can undoubtedly offer much more, but is there an increase in “value: outcomes divided by cost”? Life expectancy has increased considerably, but that’s little to do with healthcare—and unfortunately life expectancy has increased faster than healthy life expectancy, leaving women with some 20 years of unhealthy life at the end of their lives. And this measure of “unhealthy life” does not include loneliness, which I believe to be the main cause of lack of “health” among the elderly.

All of this comes to my mind when I hear talk of patient demand. Most of what I’ve written above is wholly unknown to patients, politicians, and many doctors and medical students. Yet these ideas should be part of the debate over the future of the NHS and all health systems. I prefer the phrase “patient expectations” to “patient demand” because it’s easier to recognise at once that expectations have to be fed: it makes no sense for me to expect my cancer to be cured when there is no possible cure, but if a scientists has produced a drug with even a tiny prospect of “cure” then I can begin to expect.

My wife and daughter think me heartless when I talk as I’ve written above, and I can understand that. Part of the problem is the tension between what’s “good” for populations and individuals, and ours is an age that puts individuals above populations. Medicine has to follow. But I’m not sure there’s such a tension: society essentially loses if a people with cancer are given highly expensive drugs that keep just a few of them alive for a short period; those in whom the drug has no effect gain nothing and may suffer side effects, although some might argue they are given “hope,” although it is rapidly removed; and even those who do benefit gain weeks on a life of probably 70 years, barely “material,” as accountants might say.

I believe that we have fundamental thinking to do in our relation to health and health systems, and the strains on the NHS might one day precipitate that thinking.

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.