Most doctors encounter interesting or unusual patients whose amazing stories stay with them forever. I was fortunate to look after the world’s number one story teller, Roald Dahl, as his life was ending in 1990. During my nights on call, he and I would chat into the small hours, and became friends. For decades afterwards I said little of our conversations on account of patient confidentiality. But on the 100th anniversary of his birth, his family have allowed me to describe his life long fascination with medicine and his extraordinary medical inventions which were in response to some terrible family events.

One evening, soon after we met, Dahl and I were chatting about a research paper I was writing for the Lancet.

“Ah yes…” he commented casually. “It’s a good journal. We published there many years ago . . . We invented a valve for hydrocephalus…” From the sparkle in his eye, I suspected he was teasing me. Had he really invented a neurosurgical device for this condition? In 1960, he explained, his son suffered a head injury, but the basic shunt and valve to treat the resultant hydrocephalus kept blocking.

“I couldn’t believe that with everything science had come up with,” Dahl complained, “they couldn’t produce one little clog-proof tube.” So he made his own. With paediatric neurosurgeon Kenneth Till, and Stanley Wade, a engineering friend who made model aeroplanes, he invented the Wade-Dahl-Till valve. The paper was published in The Lancet, and thousands were used around the world.

“I didn’t really do much,” Dahl told me. “I was just the go-between, finding out what Till wanted and letting Stanley know.” But years later, in researching for my book, I discovered Dahl had modestly under-stated his role. He was intimately involved in the project, devising a system of differential pressure tanks to test the valve’s operation, and even writing the first draft of the Lancet paper.

A few years later, there was family illness again. His wife Patricia Neal, the Hollywood actress, suffered a devastating haemorrhagic stroke which left her unable to talk or walk. Back then stroke rehabilitation was almost non-existent, and fearing she would become an “enormous pink cabbage,” Dahl devised an intensive rehabilitation programme, six hours daily, with the help of friends and neighbours. Her many neologisms as she relearnt to talk later inspired Gobblefunk—the mysterious mixed up language of his character, The BFG.

Pat made a remarkable recovery and thousands wanted to know the secret. So with the help of a neighbour, Dahl produced a guide outlining their approach, later developed into a book. The methods were widely adopted and led ultimately to the formation of The Stroke Association.

For some tragedies, however, even Dahl could not magic a solution. His daughter died of measles encephalitis, aged seven; this was before the vaccine was available, and he subsequently became a strong advocate for vaccination. Decades later his step-daughter died of a brain tumour. In both cases he wondered guiltily, could he have done more?

Dahl’s medical interests influenced his literature; not just his best-selling children’s book, George’s Marvellous Medicine, but also his adult short stories: in one a man’s brain is preserved alive, after his body has died; in another the “ultimate perfume” stimulates men’s olfactory nerves to drive them wild with desire. The physiology of hearing, vision, and digestion are all explored. Dahl’s research for these stories was meticulous, bringing him into contact with the profession he so admired. For me, sharing Dahl’s last few weeks and days was humbling, and the chance to now tell the untold tale of his marvellous medicine has been a privileged.

Tom Solomon is Professor of Neurological Science at the Walton Centre NHS Foundation Trust and the Director of the Institute of Infection and Global Health at the University of Liverpool. He is a passionate science communicator and tweets @RunningMadProf.

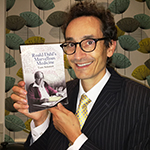

Roald Dahl’s Marvellous Medicine by Tom Solomon is published by Liverpool University press. All author’s proceeds are going to medical charities working in areas of interest to Dahl.