Wimbledon is over (well done Andy Murray), but London still has a wealth of other treats to offer. A trip to the Science Museum, for example, where the Beyond the Lab exhibition is well worth a visit. It showcases nine “citizen science innovators,” selected to illustrate how people working alone in their own homes, can devise new technologies, crowdsource data, and add to the global health research enterprise. The EU funded exhibition, co-ordinated by the European Network of Science Centres and Museums (Ecsite), has opened simultaneously in Bonn, Warsaw, and Slovenia, and will tour Europe’s science centres. Two of the innovators whose work is described are members of the BMJ‘s patient advisory panel.

Wimbledon is over (well done Andy Murray), but London still has a wealth of other treats to offer. A trip to the Science Museum, for example, where the Beyond the Lab exhibition is well worth a visit. It showcases nine “citizen science innovators,” selected to illustrate how people working alone in their own homes, can devise new technologies, crowdsource data, and add to the global health research enterprise. The EU funded exhibition, co-ordinated by the European Network of Science Centres and Museums (Ecsite), has opened simultaneously in Bonn, Warsaw, and Slovenia, and will tour Europe’s science centres. Two of the innovators whose work is described are members of the BMJ‘s patient advisory panel.

Sara Riggare, who lives with Parkinson’s disease, has developed a smart phone app which measures the speed at which she can tap her finger. The finger tapping test is used as an index of disease severity. She uses the app to adjust the dose of her medications to obtain the best disease control she can. Her exhibit includes a pair of boxing gloves. The accompanying blurb states that she sees a neurologist for one hour a year and self manages her condition for the remaining 8765; and that her hobbies include knitting as well as boxing. Michael Seres, was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at 12, and went on to have a bowel transplant. He was concerned that it was impossible to tell when his ostomy bag was full. This spurred him to devise a sensor monitor to detect this which communicates to an app on a mobile phone. What started as a DIY project has been taken up commercially.

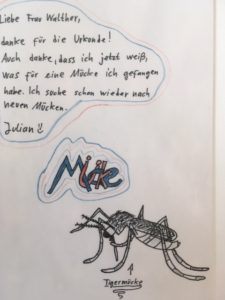

Fellow innovators include Doreen Walther, the “mosquito mapper” who crowdsources mosquitoes from across Germany and monitors the frequency of invasive disease vectors. The show case describing her Mosquito Atlas project includes letters and drawings from people who have sent her mosquitoes. What I did not spot, however, was the back story that fuelled her passion for disease surveillance. Nor how she feeds her observations into formal communicable disease surveillance channels who are monitoring the spread of diseases such as dengue and chikungunya.

Fellow innovators include Doreen Walther, the “mosquito mapper” who crowdsources mosquitoes from across Germany and monitors the frequency of invasive disease vectors. The show case describing her Mosquito Atlas project includes letters and drawings from people who have sent her mosquitoes. What I did not spot, however, was the back story that fuelled her passion for disease surveillance. Nor how she feeds her observations into formal communicable disease surveillance channels who are monitoring the spread of diseases such as dengue and chikungunya.

Tim Omer, a computer scientist living with Type 1 diabetes, has developed a low cost continuous glucose monitor and linked transmitter which can feed data into an insulin pump. These monitors are currently very expensive and not readily obtainable on the NHS. He thinks they should be—and could be, if the potential to scale up this technology was realised.

The challenge for “lone citizen scientists,” said Muki Haklay, professor of the Extreme Citizen Science Research Group who I spoke to at the exhibition, is “getting their work noticed and taken seriously by the mainstream research community.” Doctors and the journals act as gatekeepers to research, he said. One avenue he suggested is Methods of Information in Medicine, which currently has a call out for original N-of-1 trials with a focus on personal health and wellbeing and chronic disease management.

The part that individual patients, their families, and members of the public are playing in furthering research into health problems and challenges like climate change, was underlined by Michiel Buchel, president of Ecsite and director of the NEMO Science Museum in Amsterdam. He used the example of how people came together in the 1990s to tackle the HIV/AIDS epidemic as an illustration.

“Science and democracy are closely connected” he said, “and we must foster independent creativity and critical thought.” Sidestepping the word Brexit, although it was implied, he emphasised the value of EU collaboration on research, and quoted Darwin. “Those who learned to collaborate and improvise most effectively have prevailed.”

Tessa Richards is senior editor/patient partnership, The BMJ.