We’ve written before about the difficulty of recognising symptoms that could be signs of cancer, and knowing when it’s appropriate to go to the doctor about them. There’s lots of evidence that cancer is more treatable if it’s found at an earlier stage, but we know less about effective ways of encouraging people to seek help appropriately.

We’ve written before about the difficulty of recognising symptoms that could be signs of cancer, and knowing when it’s appropriate to go to the doctor about them. There’s lots of evidence that cancer is more treatable if it’s found at an earlier stage, but we know less about effective ways of encouraging people to seek help appropriately.

Encouraging people to seek help

Our new study tried to do just this. We focused on gynaecological cancers—that is ovarian, cervical, endometrial (womb/uterine), vaginal and vulval cancers which together affect over 20,000 women a year in the UK. We know from previous research that some of the things that stop people going to the doctor with symptoms are:

1) Not knowing that the symptom could be a sign of something serious

2) Worry about wasting the doctor’s time

3) Embarrassment about discussing or exposing intimate parts of the body

4) Worry about what the doctor might find

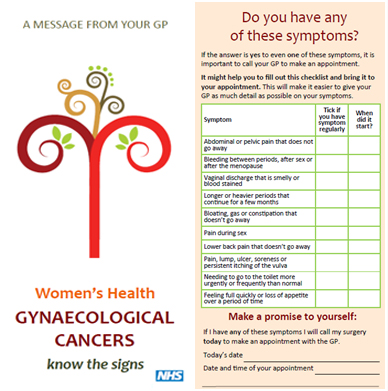

So we designed an information leaflet that addressed some of these issues. It provided information about possible symptoms of gynaecological cancer and a checklist to help women record their symptoms and make a plan to visit their GP. It reassured women that their doctor would be happy to see them, and that the symptoms were unlikely to be serious. It addressed the issue of embarrassment and reminded women they could ask to see a female doctor.

In this study, we used questionnaires to measure the impact of the leaflet in the short-term. We asked 464 women about their symptom knowledge, the things that might put them off going to the doctor if they had gynaecological symptoms, and how quickly they thought they would seek help for a range of symptoms. We also asked about how anxious they were feeling right now, so we could see if the leaflet raised anxiety levels. Women then spent some time reading the leaflet before filling in another questionnaire.

What did we find?

After reading the leaflet, most women said they would seek help more quickly if they noticed one of the symptoms. In particular, we reduced the number of women who said they would never seek help for vague symptoms like bloating and feeling full quickly, which can be signs of ovarian cancer. Women reported fewer barriers to visiting their GP, and greater knowledge about possible symptoms of gynaecological cancer. There was no evidence that the leaflet increased anxiety levels.

What next?

These findings are very encouraging, and suggest that a leaflet may be an effective way of encouraging prompt help seeking for these symptoms. But it’s also important to remember that it was an experimental study—women read the leaflet under controlled conditions, so it doesn’t tell us what impact the leaflet would have in a real world setting where women might be sent it in the post, or handed it at their GP surgery. Under these circumstances, they might not even read it.

In addition, we could only measure women’s anticipated help seeking, and we can’t be sure what they would really do if they had these symptoms. Even when people intend to seek help, life often gets in the way, other things take priority, and people don’t get round to making an appointment.

The next step will be to see what happens when we actually send the leaflet to women—will more of them seek help and, ultimately, will more cancers be diagnosed at an earlier stage when treatment is more effective? We hope to answer these questions in our future work.

Jo Waller has worked as a health psychologist at UCL for over 15 years and currently holds a Cancer Research UK career development fellowship. Her research interests include understanding cancer screening attendance, exploring responses to possible cancer symptoms and measuring the psychosocial impact of screening participation.

Competing interests: None declared.