A delegation of public health professors and specialists from the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER) visited Gaza from 5-7 June 2015, and took part in a joint meeting with the School of Public Health of the Gaza Branch of Al Quds University.

“We have 35 international aid agencies and NGOs [non-governmental organisations] in Gaza and not one of them has brought us one bag of cement,” said Dr Bassam Abu Hamad, director of the Gaza School of Public Health of Al Quds University. In a discussion of public health needs in Gaza one word comes to signify the continuing terrible plight of the Palestinian people: “cement.” Cement characterises the nature of the public health problem for Gaza. It represents reconstruction, redevelopment, restoration, proper shelter, new healthcare facilities, desalination plants, water treatment plants and power plants, and proper reconstruction of schools—which now serve as refugee accommodation. No new houses have been built in Gaza since the end of last year’s conflict.

The craters and rubble of Beit Hanoun village on the edge of the northern border of Gaza cry out for the rumble of JCBs, clearing the debris and the tangle of iron mesh extruded from concrete it once reinforced.

The only JCB in the village has its tyres shot out and is therefore itself a bigger piece of useless metal—a massive, immoveable piece of garbage among the plastic and paper that goes uncleared.

Everywhere concrete blocks stifle and strangulate any chance for development. You could add JCB parts to the list of essential public health needs, and a decent landfill site.

The children of Gaza have been immunised against childhood infections. Palestinians have been made resilient by being among the most educated in the Arab world—literacy standards and especially maternal literacy are important. “You can flatten my house, but you cannot take away my education,” says Dr Ghada Al Jadba, UNRWA [United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East] area health officer for Gaza.

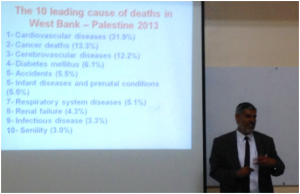

Some health indicators, and even life expectancy, hold up despite the blockade. Infectious diseases have been kept under control, but micronutrient deficiency and stunting of children’s growth are causing concern. Professor Yehia Abed, dean of the Gaza School of Public Health, describes the burden of non-communicable disease in Gaza—cancer, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases are all massive problems.

How do you go for a run among the rubble? How do you eat anything fresh when the bombs are falling? Sugar is ever present—Danone, Pepsi, Del Monte, and Nestle are still allowed in by Israel—which can hardly help the epidemic levels of diabetes and obesity.

Image: Pepsi alongside NGO vehicles at the Gaza side of the Erez checkpoint.

Mental health is less systematically monitored, but is widely acknowledged to be getting worse. Violence has also been internalised within families. An 8 year old child has experienced three wars in his or her lifetime; what peace, what fear free childhood can they imagine? And progressively, with each new bombardment, education immunises less successfully against the loss of hope. No one is blind to the daily accumulation of garbage in the streets and the absence of progress to a better environment. In the US, studies have shown the dulling impact of bad neighbourhoods. In Gaza, environmental nuisance is a fact of life and a universal presence. The air is laced with the faint aroma of municipal refuse tip.

Gaza has the world’s highest unemployment rate, 43% according to the World Bank. Work gives people status, it shows them something they couldn’t achieve on their own, it fills our time, and gives us dignity. It gives us ambition. Worklessness impacts on everyone in Gaza. So cement also comes to represent jobs—something to mobilise a nation in enforced idleness, squalor, dependency, and hopelessness.

We arrived in Gaza shortly after the Nepal earthquake; the images of destruction there resonated, but the images of relief efforts did not. Gaza continues in a worse state than many disaster areas around the world. In Nepal, the aid agencies came in expecting to restore infrastructure, expecting food aid and social welfare to be short term, expecting essential services to be re-established, and expecting to help people back onto their feet. But in Gaza that cannot happen. Eighty per cent of the population is reliant on continuing UNRWA support, because of the blockade. Nothing reaches Gaza without Israel’s approval—not cement, not gasoline, not Pepsi, not even public health professionals.

The Gaza scientific and health communities hunger for intellectual exchange. The School of Public Health in Gaza exemplifies all the best in multidisciplinary public health—their epidemiologists and health service managers demonstrate their inspiring qualities as public health practitioners. Mechanical engineers and water quality scientists, nurses and psychologists, doctors and surgeons, proudly proclaim their masters degrees in public health. As a public health community, as health specialists, as public servants, and as people who can improve health, all we can try to do is come together across sectarian divides for the benefit of the people we try to serve.

Our visit is welcomed as a source of hope—if inspirational for them, how much more so for us? We agree to plan an international meeting on public health in crisis zones next year in Gaza. If we cannot bring cement, we will nevertheless cement relations. As one of ASPHER’s past presidents Ulrich Laaser said on this visit, “Public health should be territory on which enemies can come together.”

There has to be a vision for taking away the rubble and investing in the regeneration of Gaza. As a director of public health in Sandwell in the West Midlands of England, I saw 90 of 120 high-rise blocks razed to the ground over 15 years. In some cases, like Hamilton House in Smethwick, the demolition resulted in a 95% recycling of rubble to new road projects. The costs of demolition and redevelopment are known and obviously more straightforward in the UK. But how could this be done in Gaza? The destruction has been surveyed. Someone has to calculate how to rebuild, where the rubble will go, what are the priority areas for rebuilding? Residential? Care facilities? Sanitation? Desalination? Health services? How much will it cost? William Beveridge designed a welfare state for the UK in the deepest point of the Second World War. For sure, if the cement doesn’t come, the rockets will likely continue to fly. Political leaders on both sides of the concrete wall need to change their mindsets. If there is no vision the people will continue to suffer.

John Middleton FFPH, Hon FRCPL is an independent consultant in public health and honorary reader in public health at Birmingham University. He was formerly vice president of the UK Faculty of Public Health, and in this capacity he was a member of a delegation of the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER) to Gaza, 5-7 June 2015.

He has read and understood BMJ declaration on conflicts of interest and confirms that he has none.