I love to plough through the newspapers, with radio or TV news on in the background. My enjoyment can be punctured by annoyances. Recurring candidates for this personal “room 101” are ageist language and attitudes. Comparing 2015 with my youth, I’ve seen a welcome sea change in the language deemed acceptable regarding race, sexuality, or disability—whether in the street or in the media. Yet ageist terminology remains far from taboo.

I love to plough through the newspapers, with radio or TV news on in the background. My enjoyment can be punctured by annoyances. Recurring candidates for this personal “room 101” are ageist language and attitudes. Comparing 2015 with my youth, I’ve seen a welcome sea change in the language deemed acceptable regarding race, sexuality, or disability—whether in the street or in the media. Yet ageist terminology remains far from taboo.

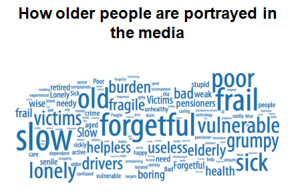

Older people are occasionally vilified, often mocked, and usually patronised. In media representations they are either invisible (“out of sight out of mind” when it comes to, for instance, care home residents or the housebound); portrayed as vulnerable and victims; or “allowed in” if they are “spritely” or “good for their age.” As for demeaning language? It’s often used unwittingly or with kindly intentions. But it embodies and shapes values and attitudes and, in turn, the services we provide.

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve seen older people marooned in acute hospitals and awaiting step down services referred to as “bed blockers”—most recently in the Independent. The story highlighted a key issue: the effect of cuts to social and community health services. But the terminology paints older people as a nuisance or threat to our system, “blocking” our beds from use by more deserving folk—as if they have any control over their predicament. Besides which, on leaving hospital they would still require funded care, so “bed blockers” sets one public service against another.

Equally self-defeating are campaigns by the Daily Mail and Telegraph on “Dignity” or “Justice” for “The Elderly.” Although the former, in particular, delights in scandal, sensation, and solution free stories, these campaigns do espouse the worthy cause of better care for older people, however unhelpful the tone. “The Elderly,” by contrast, lumps all from 65 to 100 in one amorphous (vulnerable, dependent, and invisible) mass—despite many people retaining independence and control well into older age. But then our media often falsely polarise depictions of ageing—either accompanying stories with depictions of wrinkled hands and walking aids or “allowing” depictions of older people who still manage to look and act young.

Then we have catastrophising language on population ageing: the “ticking timebomb,” “grey tsunami,” or “growing burden” threatening the very viability of our public services. Demographic change is a legitimate cause for concern, but economies can grow; people staying well for longer may retire later; and older people can make a net contribution through work, volunteering, caring, grandparenting, and spending. We don’t need to stoke intergenerational conflict.

News media reflect societal values as much as shaping them. Sadly, the attitudes of some clinical staff can mirror them. This needs to change, given that any clinician training this year will be doing so with the youngest cohort of patients we’ll ever see and the care of older people with complex needs will be the main job for most of us. If journalists need to check their ageist language, then so do we.

There’s already a tacit hierarchy of prestige within the clinical professions. It favours single conditions affecting younger people and amenable to heroic, high tech cures over care and support to help older people with multiple long term conditions, frailty, or dementia live well with them. It’s also challenging and hard work. This is clearly reflected in staffing/patient ratios and recruitment.

Language plays its part here too. Clinicians aren’t immune from using ageist terms, such as “bed blocker” or “social work medicine.” I’ve heard worse, although I haven’t heard terms like “crumble” or “GOMER” for a while.

But I’ve repeatedly witnessed frail older people with medical problems that can and should be addressed being written off as having “acopia” or “social admissions.” Patients being referred to as “bed 18” or “the stroke in bed 18”—driven partly by exaggerated fears about confidentiality and anonymity, but then seeping into custom and practice. Older people with impaired cognition or communication being labelled as a “poor historian,” when it’s surely the clinician who’s the history taker. (Do we call 3 year old paediatric patients “poor historians?”) Patients assessed as having “failed” their occupational therapy assessments, betraying total ignorance of the principles behind planning care transitions or support. People with reversible delirium or disabling dementia labelled as “pleasantly confused.” I could go on with this list but you get the picture.

Finally, as if tainted by association, I’ve heard disparaging language used about services for older people and in effect those who work in them. I’ve spent 26 years as a coalface doctor so I live with and love the gallows humour in clinical teams—I’m not a killjoy. But referring to specialist teams as “elderly scare” or saying patients are “waiting for Geris” demeans the teams. It also absolves staff from doing their best for these patients, instead letting them assume that complex needs and especially rehab, discharge planning, and community interfaces are someone else’s job and not “proper medicine.”

Readers, this really isn’t a question of over-sensitivity and “political correctness gone mad.” The words we use colour the way we think and the way we practice. It really is time to mind our language.

David Oliver is a consultant physician in geriatrics and general medicine, president of the British Geriatrics Society, senior visiting fellow at the King’s Fund, and a visiting professor of medicine for older people at City University London.

Competing interests: None declared.