I spent a recent evening at an art exhibition in the trendy Shoreditch area of East London, where three young artists were presenting their work. All three artists have the chronic disease multiple sclerosis (MS). They had been given a brief of “Good out of bad,” and been asked to respond.

I spent a recent evening at an art exhibition in the trendy Shoreditch area of East London, where three young artists were presenting their work. All three artists have the chronic disease multiple sclerosis (MS). They had been given a brief of “Good out of bad,” and been asked to respond.

The project was organised by the charity Shift.MS, co-founded by George Pepper and Freddie Yauner to fill a gap in addressing the needs of young people coping with the disease, and which uses innovative ways to connect and inform MSers. The “Good out of bad” initiative drew upon George’s own experience of what he calls “MS energy” referring to the notion of post-traumatic growth—a positive alteration and adaptation in mindset when coping with serious life adversity. Through the event they wanted to highlight the variety of experiences that come from a diagnosis of MS or indeed other complex chronic diseases, and the positive outcomes that can result.

Whilst beneficial for the MSers who used the art to reflect on their diagnosis, it is a shame that these types of patient engagement events are not more widely attended by clinicians. The event illustrated important lessons to anyone caring for someone with a chronic illness. As highlighted to me not only by the exhibition, but through my conversations with MSers at the event, it was clear that MSers all have different fears, different dreams, and different approaches to their illness. A targeted conversation between clinicians and patients would help mutual understanding of what approach suits the individual, and how as healthcare professionals we can support that. As the organisers state, “the range of work is a testament to the complexity of the condition: no two people have the same experience of MS.”

“Perceiving identity”—Hannah Laycock

“Neurology’s favourite word is ‘deficit’, denoting an impairment or incapacity of neurological function: loss of speech, loss of language, loss of memory, loss of vision, loss of dexterity, loss of identity and myriad other lacks and losses of specific functions (or faculties).”—Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat [1].

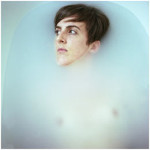

Hannah Laycock’s work was the first that I encountered. In her art she eloquently accompanies quotes from the writings of eminent neurologist Oliver Sacks with her photographs, as she aims to explore and question the notion of a neurological “lack.”

“Filling in the Gaps”—Bryony Birbeck

At a time when Bryony was preparing for a two year trip abroad, she was faced with loss of vision from optic neuritis. With her deteriorating sight and without visual information to rely on as she embarked upon a journey into the unknown, Bryony’s imagination filled in the gaps; “it was based on sounds, smells and textures; a sort of alternative reality.” “It’s a sort of alternative reality that still has the foundations of my past experience and knowledge but is peppered with images from inside my head… the physical photographs I have look dull in comparison to my own, ‘memory photographs,’” Bryony states.

“MS Medals of Honour”—Kirsty Stevens

Using her illness as an inspiration, Kirsty draws upon the shapes of the MS lesions on her MRI scans to create patterns, which she has incorporated into “medals of honour.” The medals are a reflection of the strength she has garnered from her diagnosis and from being a part of the MS army; and that being a member of this army is not something to be hidden and ashamed of. “This turns the ‘ugly and negative’ into something unrecognisably positive.”

References:

1. Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Losses (Picador: 2011), pg3, Losses (Picador: 2011), pg 3.

Julia Pakpoor is a BMJ Clegg Scholar and final year medical student at the University of Oxford.

Competing interests: None declared.