Sunday: As soon as you touch down in Freetown, Sierra Leone, Ebola hits you—or the awareness of it. Health forms to fill in, chlorine handwashes before you even enter the terminal building, zapped with a temperature gun before you step outside.

Sunday: As soon as you touch down in Freetown, Sierra Leone, Ebola hits you—or the awareness of it. Health forms to fill in, chlorine handwashes before you even enter the terminal building, zapped with a temperature gun before you step outside.

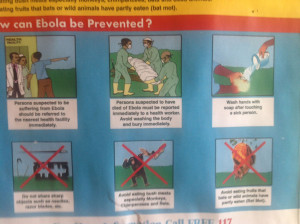

Public health messages and precautions continue throughout the city: big posters announcing that “Ebola is Real so ABC: Avoid Body Contact!” dominate the main thoroughfares. Chlorine handwashes are at the entrance to restaurants and supermarkets—but even so, I’m careful not to touch the doors with my hand. Even as medics, we have never been so clean, so hygiene aware. And we’re all getting acclimatised to the no touch policy: no touching even among the team, no handshaking when you meet someone. Instead, a crossed arm against your chest.

Public health posters in Sierra Leone © Alison Criado-Perez

The Ebola management centres in Freetown are overflowing. But in spite of this, in spite of this silent killer among us, life appears to be carrying on more or less as normal in this city of 1.2 million resilient west Africans. Markets are functioning (out of bounds to us, how can you shop in a market without touching?), roadside stalls appear to be doing a thriving business, and on the long beaches that border the city nets are being pulled up by young fishermen.

Tuesday:

And then we make the four hour drive north east to Magburaka, the site of our new Ebola management centre. It’s a vast expanse of incredible activity. With the help of about 400 workmen, the team aims to construct the management centre in about 12 days, start to finish. There aren’t enough beds in the area for all the Ebola patients, who have been enduring nightmare 10 hour journeys to the nearest centre. Many have not survived the trip, and the ambulances have been arriving with corpses among the severely ill and distressed patients.

Building the Ebola management centre in Magburaka, Sierra Leone. December 2014 © Ralf Ohnmacht/MSF

So we are pushing to get the project up and running. Already the site has been levelled and cleared, enormous warehouse tents are up, as are the tents for the patients, offering 100 bed capacity. The laboratory tent is in place, as are tents for health promotion and mental health counselling. Trenches have been dug for drainage, latrines have been established. Now labourers are constructing shelters for showers and roofs for the central walkway.

Wednesday:

Today we train the new medical national staff in the use of PPE, the personal protective equipment that you have to wear in the high risk zone. Everyone knows what it looks like now, it’s been shown enough in the media: the spaceman like outfit of bright yellow impermeable onesies, masks, hoods, goggles, gloves, white wellington boots. And a heavy rubber apron on top of everything. With temperatures in the 30s (and they will be higher in the tents), it’s almost unbearably hot inside them. Everyone pours with sweat.

We go through the ritual of dressing and undressing with the help of a dresser, who watches to make sure that everything is put on correctly, that not one square millimetre remains uncovered and vulnerable. One square millimetre is all you need for the virus to enter. The most dangerous part is the undressing, taking off the clothing that is now covered with the potentially deadly—but invisible—Ebola virus.

You are watched and advised every step of the way: now wash your hands, now take off the first pair of gloves, now wash your hands . . . chlorinated water is in abundance everywhere as, although the virus may be deadly once it enters the body, outside the body it can be killed by chlorine.

Taking a break © Alison Criado-Perez

Taking a break © Alison Criado-Perez

Everyone is tired at the end of the day; but we’re a step nearer to opening a safe management centre, with staff who know the ropes. Before I go to bed, I look through application forms for further health workers. Pitiful comments jump from the letters: killer virus . . . orphan . . . no education, no hope.

At least we will be able to offer a ray of hope.

Saturday:

The site is a frenzy of activity: carpenters with saws, hammers, and planes; electricians assessing complicated boards and hooking up lights in all the tents; water and sanitation engineers ensuring the system supplying chlorinated water is working well. Gravel is being raked over the red earth, and fences of orange netting are being erected to delineate the low risk from the high risk zone and suspect cases from probable and confirmed. From Monday, when we will accept our first patients, we won’t be able to enter the high risk area without being covered with that hot, weird, rather scary, yellow PPE.

Tomorrow we have a dry run with all the medical and hygiene staff, so we need to finish all the work today. Five hours to go . . . or maybe we’ll work through the night. I’m working with the medical team, helping unpack and organise the drugs, assemble the canvas and metal beds, and get in place all the rest of the medical equipment needed in the centre.

Everyone is busy with their own task: it’s a great atmosphere of team collaboration. Will, our project coordinator, is walking around with a look of slightly anxious concentration as he checks the whole site. He started this whole project 15 days ago. He must be feeling pretty satisfied with the result.

Sunday:

We show around some visitors from the organisational command centre, where the British Army is collaborating with the local authorities. “Puts the Royal Engineers to shame,” one soldier comments, when I tell him this has all been constructed in 12 days.

We have a final walk through under the star studded night sky. Everyone is exhausted after a long, tiring day—indeed, a long and tiring fortnight. But we’re all elated that we’ve achieved it: we’re ready to open.

Tomorrow we will receive our first patients, who are already confirmed to have Ebola, and currently in one of the holding centres where patients wait for a bed in a management centre. And we will give them the chance to live, to join the band of Ebola survivors.

Ali Criado-Perez is a registered nurse, with a background in accident and emergency nursing. With three grown-up children, she started working for MSF in 2007, achieving a long held ambition to work in humanitarian aid.

She’s worked on a variety of MSF missions, including as part of a team evacuating war wounded patients from Misrata, Libya, at the height of the 2011 conflict. She is currently working in Sierra Leone on the west Africa Ebola outbreak. Read more about Ali.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ali wrote this post just before Christmas. Read her latest post about the highs and lows of Ebola patient care from our up and running Ebola management centre in Magburaka, Sierra Leone.

MSF and Ebola

Since the Ebola outbreak in west Africa was officially declared on 22 March in Guinea, it has claimed 7857 lives in the region. The outbreak is the largest ever, and is currently affecting four countries in west Africa: Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Mali. Outbreaks in Nigeria and Senegal have been declared over. A separate outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo has also ended.

MSF has been responding to the west Africa Ebola outbreak since March 2014, and currently has more than 3400 staff working in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Mali.

Read more about MSF’s work on Ebola.

Please give generously to Médecins Sans Frontières

· £38 can pay for a suit to protect against Ebola virus

· £53 can send a doctor to the field for a day

· £95 can provide a year’s supply of treatment for a person living with HIV

· £153 can provide lifesaving blood transfusions for three people

You can donate:

· Online at www.msf.org.uk/thebmj

· By phone: 0800 408 3897

· £5 by texting “Doctor” to 70111*

*UK mobile networks only. You will be charged £5, plus your standard network rate. MSF will receive 100% of the £5 donation. If you have any questions please call +44 (0)207 404 6600.