It is a truth generally acknowledged that artists must suffer for their art. Also, it is widely believed (in the art community at least) that good art has its basis in the artist’s unique personal experience—and, especially among artists and critics, that a viewer is needed to “complete” the work, in that they will bring their own experience to their perception of the work.

It is a truth generally acknowledged that artists must suffer for their art. Also, it is widely believed (in the art community at least) that good art has its basis in the artist’s unique personal experience—and, especially among artists and critics, that a viewer is needed to “complete” the work, in that they will bring their own experience to their perception of the work.

“An exhibition of multimedia pieces created by two artists sharing a professional knowledge of medical environments. This exhibition brings together a series of process driven interrogations into the deconstructive and reconstructive nature of disease.”

In “Black & Blue,” an exhibition at the Freespace Gallery in Kentish Town Health Centre, London, two artists have taken the notion of “suffering for their art” to great lengths. For Chris Day, it is voluntary; for Penny Clayden, it is inescapable.

Chris and Penny are familiar with suffering and pain through their work: Chris is a respiratory therapist, treating cardiac patients, and Penny is a nurse, now training other nurses how to look after their backs, for she has long had chronic back pain herself. They are both nearing the end of their art MA at the University for the Creative Arts, Farnham, brought together by their medical background and their search for how to integrate their creativity and these concerns with pain, suffering, healing, harmony, natural rhythms.

Night Waves (2013) Chris Day. Acrylic ink, sea water.

Chris’s focus is on the interaction of man and nature over time, and the work she shows originates in her relationship with the sea. She has used ink and seawater to produce a series of drawings, often through wetting the drawn lines by taking the paper into the breaking waves. She works at the seashore throughout the year, and has also drawn while immersed up to the neck, unable to see the drawing on her board through watching for the next wave so that she can jump to stay above it.

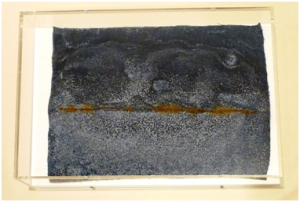

Intervention 1 (2013) Chris Day. Linen, pre-rusted wire, sea water.

Her stitched work doesn’t imitate surgical sutures—surgical procedures are presented in a more abstract form, for instance in Intervention 1 by the incorporation of wire into a linen cloth that sat in evaporating sea water for more than a year, rusting the metal and precipitating salt crystals as it dried.

Redacted Revealed (detail) (2014) Penny Clayden. Silk organza.

Redacted Revealed (detail) (2014) Penny Clayden. Silk organza.

Everyone who suffers pain sees it differently, says Penny—her own pain is black—and it was this interest in the perception of pain that led to her MA project, which was initially to discover other people’s perceptions of pain.

She found, though, that she didn’t understand her own perceptions, so she has narrowed her focus to her personal experience. One of the resulting works, Redacted Revealed, is a series of prints on freely hanging silk organza, a fabric that had been used inside plaster casts to prevent rubbing from damaging the patient’s skin. The fabric is stained with myrobalans, which, as well as being used in tanning leather in India, are made from trees that have healing qualities. Hung around a large space, the series of prints represent a day in the life of Penny’s pain, which changes over time and throughout the day. The shapes on the cloth bear some resemblance to structures found on x-rays.

Fragmentation series (2014) Penny Clayden. Porcelain, cloth, thread, loofah

Fragmentation series (2014) Penny Clayden. Porcelain, cloth, thread, loofah

Other fabrics used in the medical setting include calico and gauze, bandages and garments, and Penny has dipped these into black porcelain slip. The fabrics are burnt away during firing in the kiln, leaving the hard, but fragile, porcelain; even when the pain goes away, Penny says she can feel very fragile.

Fragmentation series (2014) Penny Clayden. Porcelain, bone china, loofah

Fragmentation series (2014) Penny Clayden. Porcelain, bone china, loofah

These visual ways of explaining pain were well received by patients who happened to be in the health centre while the show was being hung. One said that this reminded her that people outside the health setting were caring for her in a different way; another, who had been looking very dejected, seemed revived by the activity around him.

The arts in healthcare settings are acknowledged as contributing to patients’ welfare and recovery, and enriching the lives of staff and visitors. A literature is building up on the active use of art in hospitals and health centres, not just traditional pictures as something to look at while waiting, but as part of signage and for orientation within the building; as a focus for conversations between visitors and patients; making the building interesting for children; introducing the healing benefits of nature; and involving patients in creating art themselves. Funding for such art is usually from private and charitable sources.

In both art galleries and health centres, space is becoming more fluid—used for different purposes by different groups of people—for example, to meet for coffee rather than look at the art, or to see the art rather than attend a medical appointment.

The gallery at Kentish Town Health Centre is not separate from the treatment areas. It shows art that can be comforting, or which can present a challenge to the viewer. When the art is based in an experience that patients can relate to—even a difficult experience like pain—it is their own experience, their perception, and recognition of that commonality in the art work, that makes the work complete.

Black & Blue is showing at Free Space Gallery, First floor, 2 Bartholomew Road, London NW5 2BX, until 16 January 2015; see freespacegallery.org.

After two decades at The BMJ as a technical editor, Margaret Cooter went on to art school, obtaining an MA from Camberwell (University of the Arts London) in 2012.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.