The dry New Mexico wind whips up a dust cloud in the distance. Alone on a highway that stretches for miles through expanses of arid desert soil, I am travelling to visit Donald Chee, a public health community liaison at Diné College, the first Indian*-owned college in the USA. “Diné,” in Navajo, means “The People,” referring to Navajo Native Americans (NA). Located at multiple sites in the Navajo Nation (a 27,000 square mile area in Southwest USA, formerly called a reservation, now colloquially known as “the Res”), since 1991 Diné College has provided an HIV/AIDS education program to students and the wider community.

The incidence of HIV in the Navajo Nation is increasing. According to an Indian Health Service report, 47 new cases were diagnosed in 2012, up by 20% from 2011. This may in part reflect increased diagnosis, but health workers like Chee are also concerned about new transmission. Furthermore, stigma and lack of awareness may hamper early diagnosis and intervention. The Diné College HIV program aims to tackle such problems in a culturally sensitive way.

It operates from an unassuming portacabin where, Chee explains, service users feel at ease. Free, anonymous “rapid HIV tests” are offered, with results in minutes. Additionally, students are trained in peer-to-peer education and outreach. I glance at the whiteboard, on which are listed several training modules. My interest is piqued by module 2, “Diné be’iina Tidilyaa,” or “Historical Trauma,” which is taught before “HIV/AIDS prevention.” What is historical trauma? Why is it so important in this context?

Historical trauma theory is relatively new to public health. It is based on the premise that populations “historically subjected to long-term, mass trauma—colonialism, slavery, war, genocide—exhibit a higher prevalence of disease even several generations after the original trauma occurred.” (Sotero, 2006)

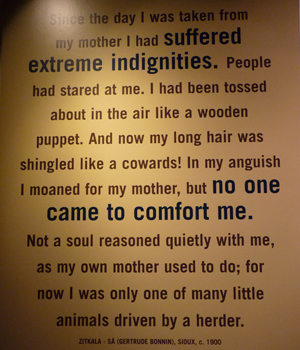

In the context of NA history, narratives of invasion, subjugation, and massacre by foreign powers are better recognised than those of displacement, resettlement, and forced cultural assimilation. The Long Walk of the 1860s exemplifies the latter. Following increasing tensions between the US government and various NA tribes, 10,000 NA men, women, and children were forcibly marched 500km from their homelands by the US Army to tiny encampments in remote New Mexico; nearly a third died from disease, hunger, and exposure. Later, in an attempt to Americanise NA children, hundreds of federally run boarding schools were established; a poignant exhibition at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona displays some of their testimonies.

Tales like these speak of cultures, languages, even names, extracted from their owners like teeth; braids shorn by powers asserting moral and cultural superiority—however well-intentioned—with unwavering confidence. I can understand how this might affect a collective psyche; how self-worth, self-expression, sexuality, parenting, diet, use of government services, and other beliefs and behaviours, may be altered. How even normality may be redefined as cultural frames of reference are beaten and recast in the mould of the hegemon. What I find harder to stomach is that all this may leave a lasting legacy to future generations.

A key element of historical trauma theory, conceptualised in this model by Sotero, is that the consequences of the initial trauma—for example malnutrition, infectious and chronic diseases, and mental health problems—are transmitted to subsequent generations through complex physiological, social, and environmental pathways. But is any of this relevant to modern life on the Res or to Diné’s HIV program?

Despite frequent romanticising of NA culture, real problems exist on the ground, including some of the worst national health and poverty indicators. Looking around the town dotted with trailer homes and casinos, I see the infiltration of large corporations, their billboards everywhere, advertising junk food, tobacco, and liquor. Alcohol misuse and other potential by-products of historical trauma, such as domestic violence and high-risk sexual behaviour, can contribute to HIV transmission and a poor prognosis, particularly in women (Simoni, Sehgal, & Walters, 2004). Recognising this, the Diné College program is seeking funding to partner with a community based organisation that specialises in substance abuse.

Programs like this, staffed by dedicated individuals like Chee, provide hope for a better future. Historical trauma is not an automatic road to self destruction and neither, of course, can all societal ills can be attributed to it. Historical narratives are multifaceted and mutable. But they matter. If professionals and policymakers can understand the role of historical trauma in NA and minority health, they may, for example, think twice before ascribing ill health solely to the “cultural” practices (dietary, sexual etc.) of an entire community, or before steaming ahead with unworkable management models. This might turn blame into empowerment, providing much needed armour in the battle against health disparities.

Acknowledgements: With sincere thanks to Donald Chee, Darlene V. Hunt and Dine College, the Indian Health Service and Hannabah Blue for allowing this experience to happen.

The Dine College HIV program is funded by the CDC (United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, an agency of the US Department of Health and Human Services) and the New Mexico Department of Health. For more information, visit http://www.dinecollege.edu/institutes/hiv/hiv.php.

* the terms “Indian” and “Native American” are used interchangeably by locals, and the former is not considered offensive.

Suchita Shah is a general practitioner in Oxford, UK. She is currently living in Boston and is a student at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

References:

Simoni JM, Sehgal S, & Walters KL (2004). Triangle of Risk: Urban American Indian Women’s Sexual Trauma, Injection Drug Use, and HIV Sexual Risk Behaviors. AIDS and Behavior, 8(1), 33–45. doi:10.1023/B:AIBE.0000017524.40093.6b

Sotero M. (2006). A Conceptual Model of Historical Trauma: Implications for Public Health Practice and Research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 1(1), 93–308.