I sit and type this in my lounge, with the men’s Olympic football final on the TV in the background (Mexico are 1-0 up against Brazil can you believe), and look forward to my final shift as an emergency care doctor at the London 2012 Olympics starting early the next day at 6.30am.

I sit and type this in my lounge, with the men’s Olympic football final on the TV in the background (Mexico are 1-0 up against Brazil can you believe), and look forward to my final shift as an emergency care doctor at the London 2012 Olympics starting early the next day at 6.30am.

I reflect back to my first shift a few weeks ago and smile at how clueless I felt then. It was the day after Danny Boyle’s exhilarating and awe-inspiring opening ceremony, and I had a spring in my step despite waking at 4.30am to arrive on time. I crammed in some reading on the train and took the first of many deep breaths. I eventually arrived at Stratford International station along with the hoards of other bewildered purple and beige clad volunteers and felt my heart sink. The similarity of this scene to a typical first day at a new hospital (or, even worse, a first day at school) was uncanny and the unwelcome feelings of fear, defeat, and insecurity took over.

Unintentionally paying homage to a typical first day, I ended up going to the wrong place and cursed myself for not attending any of the pre-placement briefing events. I eventually left the bustling Olympic Park—where I wasn’t meant to be—and arrived 45 minutes late at the much more civilised Olympic Village—where I was meant to be. Then I was shepherded into the “polyclinic.” The fact that I was late and had not done any preparation was not even mentioned as I was warmly greeted by Andrew Rees, the polyclinic team lead, who gave me a guided tour of the building and took time to answer all my questions about what exactly I was meant to be doing.

Unintentionally paying homage to a typical first day, I ended up going to the wrong place and cursed myself for not attending any of the pre-placement briefing events. I eventually left the bustling Olympic Park—where I wasn’t meant to be—and arrived 45 minutes late at the much more civilised Olympic Village—where I was meant to be. Then I was shepherded into the “polyclinic.” The fact that I was late and had not done any preparation was not even mentioned as I was warmly greeted by Andrew Rees, the polyclinic team lead, who gave me a guided tour of the building and took time to answer all my questions about what exactly I was meant to be doing.

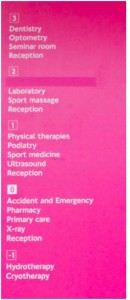

The polyclinic itself was quite a sight to behold. It is an impressively constructed modern three-storey building shaped like a pyramid and housing specialist departments to cater for all the athletes’ needs. On the third floor was the staff area where Andrew started the tour by showing me the adjacent ophthalmology department and the dental section. Descending the central staircase to the second floor led us to the pathology labs, sports massage, and the appliance centre. Down another flight of stairs led to the radiology department, the sports medics, physiotherapists, and podiatry. And finally down on the ground floor was where the pharmacy, primary care, and reception were to be found. I was taken to where I would be spending my shifts—the Emergency Department (ED) and it was only then that I noticed the huge mobile MRI and CT scanners parked outside the entrance to the building.

The polyclinic itself was quite a sight to behold. It is an impressively constructed modern three-storey building shaped like a pyramid and housing specialist departments to cater for all the athletes’ needs. On the third floor was the staff area where Andrew started the tour by showing me the adjacent ophthalmology department and the dental section. Descending the central staircase to the second floor led us to the pathology labs, sports massage, and the appliance centre. Down another flight of stairs led to the radiology department, the sports medics, physiotherapists, and podiatry. And finally down on the ground floor was where the pharmacy, primary care, and reception were to be found. I was taken to where I would be spending my shifts—the Emergency Department (ED) and it was only then that I noticed the huge mobile MRI and CT scanners parked outside the entrance to the building.

The emergency department itself had six cubicles, three of which were designated consultation areas containing chairs, and the remaining three cubicles contained trolleys for patient examination. Most of the basic essential A&E equipment was available and there were resus kits on standby in case of emergency. I was also introduced to the medical encounter system where all medical information was stored—the Olympic version of the electronic patient record (EPR).

The emergency department itself had six cubicles, three of which were designated consultation areas containing chairs, and the remaining three cubicles contained trolleys for patient examination. Most of the basic essential A&E equipment was available and there were resus kits on standby in case of emergency. I was also introduced to the medical encounter system where all medical information was stored—the Olympic version of the electronic patient record (EPR).

I met my colleagues in the ED and soon realised how much people had sacrificed to be a part of London 2012. In addition to travelling to London to attend all the training events in the months leading up to these two weeks, I met doctors and nurses from all over the UK who were sleeping on friends’ couches, working all hours of the night, working for free, and taking annual leave just to be part of the team. Speaking of team, working my first shift reminded me of all the things I’ve missed since leaving clinical medicine—the immediate camaraderie when a new team comes together, the debates about which is the best intravenous fluid to use, the exchange of terrible (or amusing) medical anecdotes…and unexpectedly bumping into a few old colleagues.

Having spent the last three years working in global health, and previously as a surgical registrar, I initially felt slightly out of my depth in my new role as an “emergency care doctor.” Especially after I discovered that our patient pool included the prestigious athletes. I found it reassuring that we were provided with a prescribing formulary based on the BNF that lists which medications are permitted and which are prohibited for competing athletes. It was interesting to learn that there were notable exclusions for specific athletes e.g. beta blockers were prohibited in archery (and presumably any other sport that required a steady hand). If a prohibited substance was necessary for an athlete who was unwell (e.g. epinephrine for anaphylaxis, or opiates for pain relief), a therapeutic use exemption (TUE) had to be granted by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) TUE Department. In most emergencies, gaining a TUE in advance was impossible as the health of the athletes took priority. Any necessary treatment was administered and the TUE was obtained retrospectively after consultation with the polyclinic team lead. The other ED staff and I had also been advised that the sports medicine doctors must see all athletes, regardless of their presenting complaint. However, the door to the ED was situated sensibly within a stones throw from the entrance to the polyclinic, hence most visitors (athlete or not) presented to us initially before finding their way to the correct department.

In addition to the athletes, the polyclinic also provided care to the entire Olympic and Paralympic Family: IOC officials, security, armed forces, volunteer workforce, and any other accredited personnel who happened to be in the Olympic village. For London-based patients, we were able to provide them with enough treatment for the next 24 hours, and they were advised to see their regular GP the next working day. For international patients, we were able to issue prescriptions for seven days, which were dispensed by the on-site pharmacy. The ED provided a 24-hour service encompassing three shifts, with each shift being manned by at least one emergency doctor, emergency nurse, general practitioner, and primary care nurse. I did notice a few observation rooms that were situated away from the din of the main department that could have been used for patients overnight, however there had been little demand for their use. There was also a paramedic and ambulance service available for transfer of critically ill or injured patients to hospital—in our case, the Homerton Hospital was the referral hospital of choice.

Fully armed with all this information, I was ready to see my first patient: an athlete who had suffered a post micturition syncope. Each country had a team doctor, who was usually the first port of call for any ailing athlete and the team doctor in this situation had already applied the glue and steri-strip to the superficial laceration to the forehead. There were no alarming findings on history or examination so ordinarily I would have discharged the patient after a period of observation. But I was quick to learn that this was no ordinary situation. The team doctor listed the investigations he wanted and, after a healthy debate, we agreed to do a full set of bloods, CT head, and ECG—which were thankfully normal (and kept the echocardiogram, CT neck, and tilt test for a rainy day). I wished the athlete and their entourage the best of luck and they were quickly on their way.

A mixture of athletes from other nations and disciplines visited the ED that day—including a handball player with a dislocated patella, a hockey player with a splinter in her foot, and a gymnast with a Lisfranc injury patiently waiting for his MRI as we watched his injury being broadcast on the BBC! A common request was for the team doctors to request a full set of bloods for their athletes who hadn’t performed well in their events, which I found peculiar, but duly obliged. A lot of my time was therefore spent taking blood tests from athletes (who all have great veins, phew) and then chasing the results.

The medical problems of the non-athletes were more representative of the bread and butter pathology of an emergency department—diarrhoea and vomiting, poor diabetic control, acute asthma, headaches, UTIs, and DVTs. The spectrum of services that the polyclinic provided and the speed with which these services could be accessed was second to none. Bloods were taken and processed usually within a couple of hours, imaging was almost immediately available, consultation with specialists and experts arranged with no fuss—it was certainly the most seamless medical experience that I’ve ever been lucky enough to be a part of.

What I found most uplifting was the vibe and general buzz of the polyclinic and the entire village. Everyone I met had a smile and a cheer and seemed so pleased to be there. In retrospect, I realise this may have been due to the rapidly depleting stocks of free condoms available from the pharmacy…but maybe it was also because everyone knew that being a part of London 2012 was something special. Nobody said “no” and most people bent over backwards to help each other out. This was altruism at its best. As I finish this article, Mexico have beaten Brazil and Mo Farah has won the second of his two gold medals. Dreams can and do come true, and my experience as an Olympic village doctor during London 2012 has certainly been a privilege.

Sophie Reshamwalla worked in London as a surgical registrar before completing a Master’s degree and the DTM&H at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. She spent a year working at THET (Tropical Health and Education Trust) and currently works as the implementation manager at Lifebox Foundation (www.lifebox.org).