In a recent case report, Marthinus Jacobus Hartman and colleagues report the successful laparoscopic removal of a thorn granuloma from the abdomen of a wild captive cheetah.

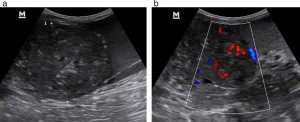

An 11-year-old cheetah was presented for routine laparoscopic ovariectomy during a cheetah sterilisation project in Namibia. While under anaesthesia, a mid-abdominal mass was palpated and visualised by ultrasonography as a highly vascularised round 6 cm diameter well-vascularised mass, not associated with any specific abdominal organ, in the mid right abdominal cavity (Fig 1). Ultrasound-guided fluid aspiration revealed a cloudy and turbid-appearing fluid, which on centrifugation had a sizeable cellular pellet.

The differential diagnoses considered before surgery were intraomental neoplasia or a foreign body granuloma.

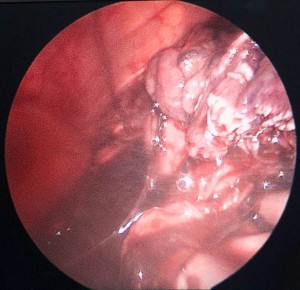

The cheetah was prepared for laparoscopy for ovariectomy and surgical removal of the mass. A single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) port was placed immediately caudal to the umbilicus, and the mass embedded in omentum (Fig 2) was found, secured and freed using coagulation without major haemorrhage.

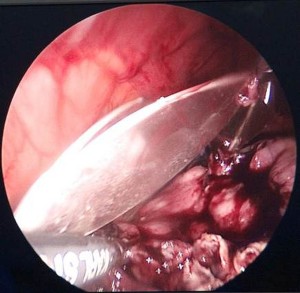

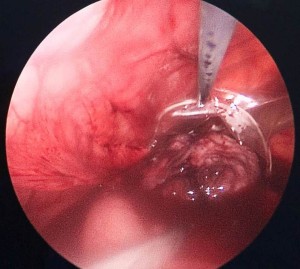

After introduction of the extraction bag through the SILS port (Fig 3) and intra-abdominal deployment (Fig 4), the mass was placed into the bag (Fig 5) and retrieved through the port. Ovariectomy was completed and the peritoneal cavity was lavaged before the surgical site was routinely closed.

The patient recovered uneventfully.

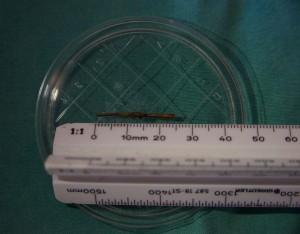

Subsequent macroscopic examination of the excised mass revealed a firm yellow-white soft tissue mass containing a 25 mm thorn-like structure (Fig 6) resembling that of the Sickle or Chinese lantern bush, a common thorn tree in Northern Namibia.

This is the first report to describe the laparoscopic removal of a foreign body-induced granuloma from the abdomen of a cheetah. Granuloma formation in this species has not been well described. Similarly, reports on laparoscopic surgery in this species are sparse, particularly those describing the laparoscopic excision of abdominal masses. They have, however, been used for laparoscopy in dogs, horses and tigers using three or four separate ports. The use of these bags or pouches has also not been described with SILS.

Entrance of the thorn into the abdominal cavity remains speculative, but it could have either entered percutaneously or via the gastrointestinal tract

This technique promises to be especially useful in wild carnivores, allowing rapid recovery and lowering the risk of postoperative surgical wound complications.

A much more detailed account with further pictures and a video clip of the procedure can be found here.