Simulation is an educational tool that is almost ubiquitous in postgraduate medical training – with diverse examples of implementation – ranging from video recording of consultations with actors, to full immersion scenarios allowing trainees to test their skills and mettle in managing medical emergencies. Indeed, it is so established in some fields that there are contests to show off medical skills being practised under pressure to draw out lessons. SIMwars plays out at the SMACC conference each year to great fanfare.

But what if you aren’t planning to demonstrate the perfect RSI on stage or in a video for dissemination around the world? What if you are just doing your day job – how would you feel, and would it be any use to suddenly find Resusci Annie in the side room you really need for a patient with c-diff, and be expected to resuscitate her from a life-threatening condition?

A paper in the current issue of the PMJ looks at just this – the perception and impact of unannounced simulation events on a labour ward in Denmark.

The research team had planned to carry out 10 in situ simulations (ISS), but only managed 5 owing to workload issues in the target department. The response rate to questionnaires before and after the ISS events was strong. Within the questionnaire were items concerning the experience of participating in an unannounced ISS – namely the perceived unpleasantness of taking part in an unannounced ISS, and anxiety about participation in the same.

One third of the respondents reported that, even after participating in an unannounced ISS, they found the experience stressful and unpleasant, however, 75% of them reported that participating in an ISS would prepare them better for future real-life emergencies. The corresponding numbers for non-participants were a third thinking the experience would be stressful and unpleasant, but interestingly – only a third thought participating would be beneficial to them.

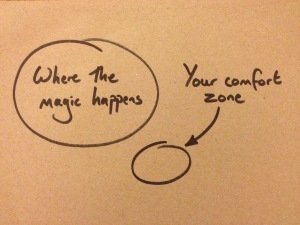

These results made me think about the experience of learning, and if the experience is ever relaxing and pleasant if it is truly effective?

I can’t think of many learning environments where I have felt completely at ease providing me with really deep learning, food for thought, or opportunities for development. Indeed – a great number of my most profound learning experiences, that have taught me lessons I carry with me today – have been truly unpleasant. These rich educational experiences tend to have involved challenge – requiring justification for a course of action, or the challenge of making a decision that is later to be judged through clinical outcomes, or a challenge to my strongly held beliefs – requiring an exploration of opinions, morals or prejudices.

Now, not all of these experiences have been publicly unpleasant – observed by others, but all have been relatively uncomfortable in different ways. And perhaps this is key to deep learning – that it requires examination, challenge and reflection, not just sitting passively in a lecture theatre being told facts, or actions to take in a particular scenario.

So when we look at educational interventions employed in postgraduate medical education nowadays, have we lost a little of the challenge that used to be such a prominent part of the ‘learning by humiliation’ approach? We perhaps don’t need to return to the days of Sir Lancelott Spratt.

But equally we shouldn’t shy too far away from the idea that learners require a degree of challenge, discomfort, and even unpleasantness to gain insights into how their knowledge is being put into action, and it is far better to receive that challenge within the simulated environment than to have to face those challenges in real life, without the chance to re-run if things don’t go so well.