Over the course of a day, a gynaecologist will care for patients with a wide range of presentations—from a premature baby who doesn’t survive beyond the first nights whose young mother has had previous treatment for precursors of cervical cancer, to the stress of another woman in a colposcopy clinic worried about the management of moderate risk precancerous changes in her cervix before her 30th birthday. Both cases highlight the importance of considering benefits and harms in medical interventions. Although the treatments for cervical cancer precursors are very effective in prevention, they also substantially increase the risk of reproductive morbidity, especially preterm birth.

There is a wide body of evidence that needs to be considered. Abnormal smear results and cervical lesions that potentially warrant intervention are very common. For instance, in England alone, approximately 3.6 million women aged 25 to 64 annually attend cervical screening, and almost 24 000 cervical procedures are carried out.

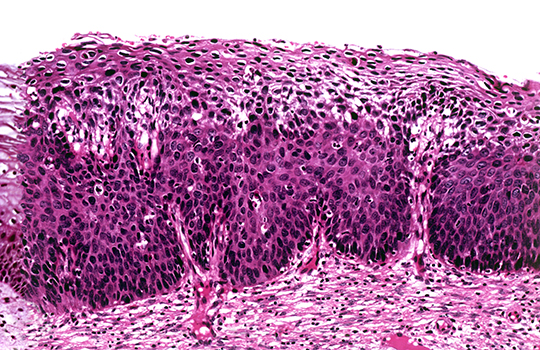

Although the intention is to prevent problems, these smear results also generate anxiety and concern, as well as cost. Historically, almost all changes detected in cervical smears were treated. However, as our evidence base has developed, it has become apparent that the mildest uterine cervical lesions typically regress spontaneously. This finding has shifted clinical practice guidelines to a more conservative approach with active surveillance, and surgical treatment only if the lesion persists or progresses. Simultaneously, an increasing body of evidence has emerged suggesting that even moderate precancerous lesions (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2, CIN2) may regress, especially in young women. A robust synthesis of evidence for this approach, however, has been lacking.

At the same time, however, the World Health Organization has decided to reclassify the histopathological terminology of cervical cancer precursors by dividing them from three (CIN1 to 3) to two groups (low grade and high grade). The former CIN2 (or moderate dysplasia) is now grouped together with CIN3 as “high grade.” This means that many women with possibly spontaneously regressing lesions are classified as having high grade lesions warranting treatment, with increased risk of future reproductive morbidity.

Underlined by a trial conducted several decades ago in New Zealand, where untreated CIN3 resulted in numerous cases of invasive cancer, there is a wide consensus that treatment is always warranted for CIN3. Even though there are challenges in differentiating between CIN2 and CIN3, we feel that the increasing evidence of frequent regression of CIN2 should not be forgotten. Indeed, widespread adaptation of WHO’s classification could cause substantial overdiagnosis and overtreatment,and also prevent more personalised care of young women with CIN2 lesions.

We therefore decided to systematically appraise the existing evidence for the natural history of CIN2 lesions: to estimate what happens if we do not immediately treat them. Pooled estimates from 36 studies (among over 3000 women) showed that half of the lesions regress spontaneously within two years of surveillance. In young women in particular, expectant management is a valid option, as, in this group, up to 60% of CIN2 lesions regress under active surveillance within two years, and progression is extremely rare. This does not mean, however, that all women should be “left untreated”. Women’s values and preferences, fears, desires, and ability to commit to long term follow-up need to be considered and individually discussed. Moreover, the resources of the colposcopy units and adjoined pathology departments need to be taken into account.

Our results showed that active surveillance is a valid strategy for managing CIN2, however, decisions about management are preference sensitive. We hope that our findings will be useful for women and their care providers in making decisions about the management of CIN2 lesions. Future studies will hopefully provide more insights and refine management decisions.

K Tainio, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital, Finland.

K Tainio, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital, Finland.

KAO Tikkinen, Departments of Urology and Public Health, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital, Finland.

KAO Tikkinen, Departments of Urology and Public Health, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital, Finland.

M Kyrgiou, Institute of Reproduction and Developmental Biology, Department of Surgery & Cancer, Imperial College, London, UK, and West London Gynaecological Cancer Center, Queen Charlotte’s & Chelsea, Hammersmith Hospital, Imperial Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK.

M Kyrgiou, Institute of Reproduction and Developmental Biology, Department of Surgery & Cancer, Imperial College, London, UK, and West London Gynaecological Cancer Center, Queen Charlotte’s & Chelsea, Hammersmith Hospital, Imperial Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK.

I Kalliala, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital, Finland and Institute of Reproduction and Developmental Biology, Department of Surgery & Cancer, Imperial College, London, UK.

I Kalliala, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital, Finland and Institute of Reproduction and Developmental Biology, Department of Surgery & Cancer, Imperial College, London, UK.

Competing interests: K Tainio: consulting fees (Gedeon Richter). Others: none declared.