I work at a great place in the UK. We have gorgeous facilities, friendly staff, great benefits, and—most important to this American doctor—unlimited free coffee (and tea if you’re British).

I work at a great place in the UK. We have gorgeous facilities, friendly staff, great benefits, and—most important to this American doctor—unlimited free coffee (and tea if you’re British).

But this summer, I will be heading back to clinical medicine. In preparation, I have been thinking a lot about what I have mentally termed the “emotionals:” emotional labour, intelligence, and resilience.

Emotional Rollercoaster

In my early twenties, someone told me, “I don’t understand why medical students complain so much about how hard it is—they knew what they were getting themselves into.” And to my shame, I nodded.

What I understand now, after training at Harvard Medical School, is that medical students have no idea what they are getting themselves into. There is simply no way to fully understand what it will feel like to sit with a family as they absorb the news that their loved one has passed away, and then—without pause—have to greet a different patient with a smile and an open heart.

It’s impossible to communicate how it feels to deliver a baby and witness the joy as a new family is created, and then walk into a room where the air is thick with concern about an abnormal fetal heartbeat, and to have to explain to the anxious mother that her worst fears might be coming true.

The daily emotional roller coaster is terrifying, exhilarating, difficult, and rewarding. At its best—when you have a safe place and adequate time to process all of the emotions—the rollercoaster keeps you coming back every day. At its worst, it can destroy you.

Emotional Labour

It turns out that this emotional rollercoaster has an academic name: “emotional labour.” “Emotional labour” is the concept that as humans, we regularly work to change our emotions by modulating our thoughts, physical reactions, and emotional expression. We all do it to varying extents.

For health professionals, “emotional labour” is at the core of the job. And yet, “research suggests that cumulatively, ongoing emotional work is exhausting but rarely acknowledged as a legitimate strain.” As such, the exhausting rollercoaster eventually causes burn-out, dissatisfaction, and stress—all things we know lead to poor patient care and low retention rates.

Emotional Resilience and Intelligence

But the rollercoaster can be done well, and can even be a source of deep fulfillment. Some of the most promising ways on how to do this are discussed in a body of literature around “emotional resilience” and “emotional intelligence.”

“Emotional intelligence” is “the capacity for recognizing our own feelings and those of others, for motivating ourselves, and for managing emotions well in ourselves and in our relationships.” Developing emotional intelligence can be an important way of coping with emotional labour.

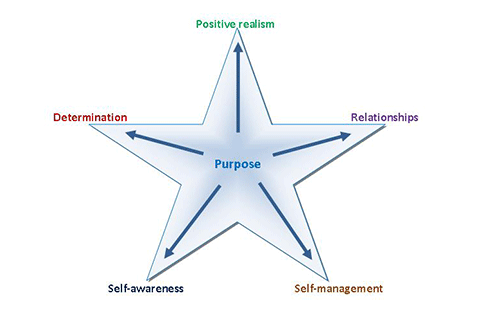

“Emotional resilience” describes how people “bounce back” from adversity, through a set of actions and behaviours. In general, resilient people have components of emotional intelligence—self-awareness and self-management—while also having strong relationships, determinations, and “positive realism”—the act of making concrete steps in a positive direction.

Emotional Employers?

Both emotional intelligence and emotional labour are great tools to reflect on and use as I re-enter clinical medicine. However, these concepts still focus on what I can personally do to protect myself. This is necessary but not sufficient: it feels like a foreman telling the construction worker to “be aware of your physical surroundings” without providing the worker with a hard hat and a safety harness.

As the world’s fifth largest employer, the NHS could revolutionize the standard of “occupational safety” by providing the emotional equivalents of safety gear. With the concepts I outlined above, the framework for this already exists; the questions only need to be asked.

As I head back to clinical medicine, the top thing on my wish list from employers would be an environment in which it was acceptable to take time to nurture relationships and practice emotional intelligence. Actually, I would want an environment where it was unacceptable NOT to take that time.

I’ve been fortunate to work in this type of environment for the past year, and I have taken the opportunity to strengthen my resilience and practice emotional intelligence. But how long can I maintain these practices without the necessary time? How long until the rollercoaster makes me sick?

Sara Martin is finishing her training at Harvard Medical School after working in health policy for the NHS this past year.