Going native: the right way forward for advertisers?

5 Nov, 13 | by BMJ

Earlier this year we introduced the concept of native advertising, which in the context of the advertising world, is still a relatively new concept. In the space of a few years it has developed from a burgeoning and beneficial idea to what many believe will be the advertiser’s tool of the future. Initially picked up and tested by leading digital platforms, such as Google and Youtube, native ads are now a totally integrated part of online browsing.

Social networks in particular have assimilated native ads more than any other platforms, specifically with Facebook’s suggested posts and Twitter’s promoted tweets and users:

With the declining click-through rates of banners, it came as no surprise that the likes of LinkedIn, Pinterest and Tumblr quickly integrated their individual versions of native ads as well. Having acquired Instagram, Facebook ensured that the image service too followed suit, and last week launched their sponsored ads:

So, why does this kind of ad work? The theory is that they enhance your browsing experience by fitting in seamlessly with each respective site-style in terms of both aesthetics and content. They are formatted to look like regular in-site content. The language used is less formal, in order make it inviting and feel like an ordinary user’s post. Furthermore, the content should read like other content on the site and engage users in a similar way. Whilst promoted ads on Youtube tend to be considered native ads, the fact that their content is largely irrelevant to the content a user is actually looking at, often makes them feel like an intrusion. Popular content-sharing site Buzzfeed by comparison, has been one of the standout performers in their use of native ads. With no banner ads on the site and 30 million unique monthly visitors, they recognised the marketing possibilities and excelled by understanding how users want shareable content. When they partner with advertisers to create branded content, they make sure that it’s just as good as their normal content and that it contextually fits with what you’re looking at.

Buzzfeed’s success with native ads has raised their profile so much that they now train agencies specifically on how to effectively integrate sponsored posts. Their Social Story Telling Creator program gives participating agencies a Buzzfeed approved accreditation after completing the training in how to implement branded content. And Buzzfeed aren’t the only ones. 2013 has seen a propagation of startups like Nativo who cater specifically to publishers and advertisers. For online publishers they help to implement the branded content to their sites by coding and making templates. For the advertisers they upload and distribute their content, with the correct formatting for multiple sites and different platforms such as tablets and mobiles.

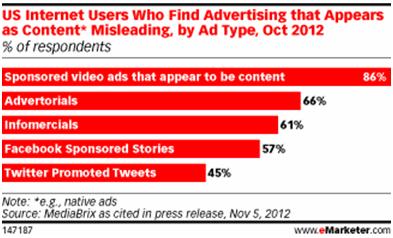

Nontheless, the growth of native ads has not been without hiccups. The lack of a comprehensive answer as to what definitively constitutes a native advert remains a constant source of debate. But even more of a problem lies in the number of users that misunderstand sponsored adverts and branded content, or find it downright misleading. Despite most, if not all, sponsored adverts bearing some sort of symbol or identifier to demarcate their status as paid-for-advertising, the subtlety of imitating the style of a site and/or appearing in the user-stream can make these ads unclear. EMarketer conducted a survey last year which demonstrated that a high number of US internet users found various types of native ads misleading:

User interaction can be another source of discontent. Online articles, for example are always open to public opinion, whether it be good or bad of course. But when an advertiser pays for a branded articles, the last thing that they want is a stream of negative comments beneath, should there be backlash. Sometimes the comment-moderation on articles can be described as uneven at best, unashamedly one-sided at worst.

Regardless of these misgivings, the growing public acceptance of native advertising is still clear. Where once there was outrage at ‘Suggested Posts’ and their invasion of the user’s Facebook stream, this has gradually faded into passive acquiescence. Rather than a hindrance, native ads are now simply the norm. This can be put down to the efforts made by advertisers to understand what people want to see and to cater to the user-experience, by minimising the levels of intrusion and producing high quality content. The content delivered is crucial to the sustainability and progression of native ads. If they continue to engage and deliver traffic, the benefits to brands, publishers and users could cement native ads position as a genuine force for marketers. But should the content levels fall below expectations or be viewed as advertising-trickery-masquerading-as-journalism, the fallout can be severe. Users are never shy to let their feelings be known, as The Atlantic found out with their ill-advised sponsored Scientology content.