By Ann Gates @exerciseworks

The newly published “Movement for Movement” editorial (Gates et al) heralds a new era of framing and dealing with the deeply entrenched life style issues that contribute to the rise in the global burden of diseases (1). It uses physical activity as a case study and identifies areas where the physical activity community must work to build capacity and cultural practices in order to implement sustainable results (2). Overall, the editorial addresses: (i) moving forward as a community of practice, (ii) initiating action by the many, and (iii) synergising the way we work together to achieve the World Health Organization goals for physical activity.

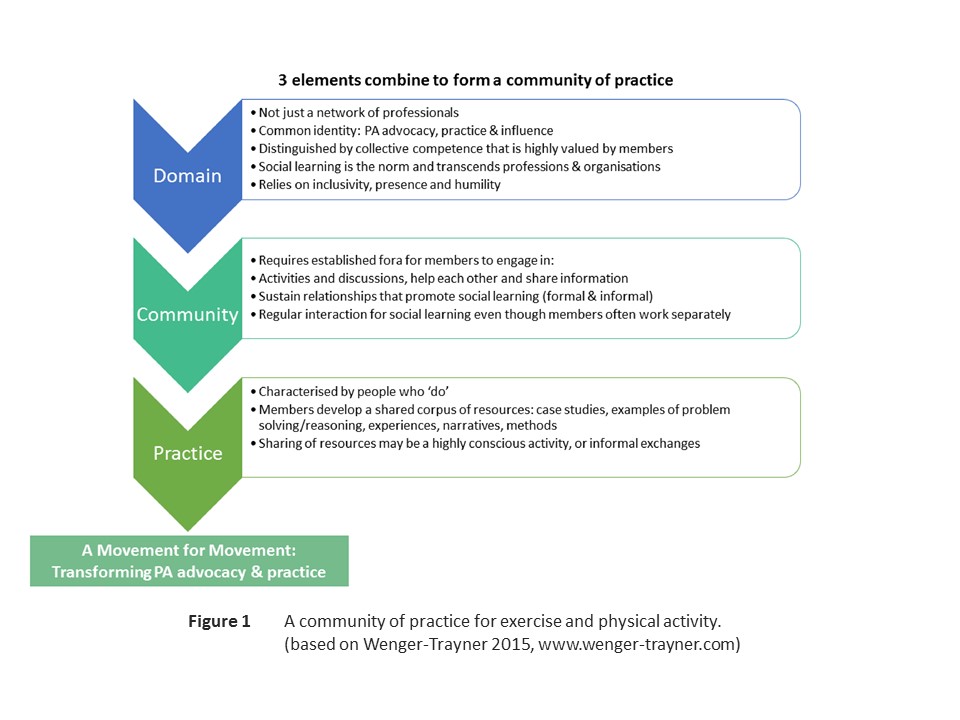

The editorial, together with Figure 1 and the web appendix, highlight positive examples from working as a “community of practice.” They also relate principles from the Impressionist Art Movement.

The Impressionist’s way of working and achievements demonstrate disruptive innovation, and different ways of working in a community of practice to propel bottom-up change. The result, was a legacy of respect for their art and culture

Attributes of the Impressionist movement fit perfectly with the wider community approach necessary to deliver physical activity guidelines and strategies. There are 3 basic elements to a community of practice: the domain, the community, and the practice (3). These basics deliver the desired operational outcomes. Figure 1 demonstrates concrete examples of how this could, should or would work (3).

How real is a community of practice for physical activity and are we already starting to work in this way?

The concept of a community of practice is not new. Further, examples of ways of working as a community of practice for physical activity are already distinguishing themselves:

- Social media is similar to the “Salon” culture of Impressionist artists, painters and patrons, as it serves as a test bed for new ideas and feedback. It provides a conduit for continuous professional development and social interest sharing. This reflects the rapid learning style of the artists and how they adapted they own techniques to create masterpieces that challenged society and the public’s perception of what constituted art. Action by physical activity advocates on social media is no different: one great “retweet or share” is rapidly adapted to real life action and further creativity!

- The use of massive open online courses provides the opportunity for all to garner knowledge and skills, but it is only the first step. Increasingly such open online courses can be supported (as opposed to just self-study) and especially by volunteers and enable sharing and caring through discussion forums and which is essential for PA implementation. It provides the platform for “conversations” and generates the community feedback needed to inspire participants to reflect and act differently. Further, it translates knowledge into everyday clinical practice and strategic influence. This mirrors the way in which the Impressionists developed their unique art style and mastery.

- By combining these new paradigms and shifting the way in which we share, learn, translate knowledge and apply skills to individuals, patients and communities, we can start to realise something special: a unique way of progressing the physical activity agenda and culture of change. The recent use of national and international infographics to convey a public health message (4) is an example of how organisations and individuals are changing the communication values of health practice.

In summary, the community of practice approach has the currency to transcend the barriers and doubters, ignore the financial politics that have prevented a societal culture of “active lives for all”, and enable a movement for movement that is truly a social, cultural –a rich movement of people who can do (5).

“A Movement for Movement” as a community of practice

So what has the art got to do with communities of practice? Perhaps Monet, describes it well: “It’s on the strength of observation and reflection that one finds a way. So we must dig and delve unceasingly”.

May we aspire to apply these community of practice principles to our own work in SEM, and disease prevention (7) – a physical activity advocacy movement that transcends (8): cultures, politics, and strategic inertia, would indeed be an impressive work of great art.

A movement for movement that can make every contact count and every influence matter for patients, communities and nations.

Let’s start painting the future together! (9)

Read the full editorial HERE.

References

- Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine – evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015 Dec;25 Suppl 3:1–72.

- Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, Lambert EV, Goenka S, Brownson RC. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. The Lancet [Internet]. 2016 Jul [cited 2016 Aug 11]; Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673616307280

- Wenger-Trayner E, Wenger-Trayner B. Introduction to communities of practice [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 Aug 11]. Available from: http://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/

- Infographics: Infographic. Make physical activity a part of daily life at all stages in life. Ann B Gates, AD Murray. Br J Sports Med bjsports-2016-096643Published Online First: 29 July 2016doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096643

- Andersen LB, Mota J, Di Pietro L. Update on the global pandemic of physical inactivity. The Lancet [Internet]. 2016 Jul [cited 2016 Aug 11]; Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673616309606

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2015 Aug;386(9995):743–800.

- le May A. Communities of Practice in Health and Social Care. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

- Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, And Identity. New Ed edition. Cambridge, U.K.; New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

- Ganz M. In: Nohria N, Khurana R, editors. Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice: A Harvard Business School Centennial. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press; 2010.

***********************

Ann Gates is a Member of the World Heart Federation Emerging Leaders Programme, Associate Editor of The British Journal of Sport and Exercise Medicine, and CEO of Exercise Works! She is passionate and interested in cultures and art.