– more data, new insights…

In 2012, the first individual patient data meta-analysis (IPDM) in the field of acupuncture was published.[1] It was also one of the first in the field of pain research. It was a struggle to publish, principally (I guess) because the IPDM method was relatively new to journal editors, and because the general medical journals tend towards conservatism and orthodoxy, so positive research on unorthodox interventions probably have higher hurdles to clear prior to publication.

The 2012 IPDM included data from 29 trials and 17 922 patients. The update has just been published, and it includes data from 39 trials and 20 827 patients.[2]

It should be noted that trials were only included where allocation concealment was unambiguously determined to be adequate, so this is a data set built on what used to be called the highest quality trials.

Trials were grouped into 3 clinical categories for analyses: osteoarthritis, chronic headache, non-specific musculoskeletal pain (back and neck pain), and shoulder pain. Acupuncture was shown to be superior to sham controls with effect sizes of 0.24 (previously 0.26), 0.16 (0.15), 0.30 (0.37) and 0.57 (0.64) respectively. Acupuncture was also shown to be superior to no acupuncture controls with effect sizes of 0.63 (0.57), 0.44 (0.42) and 0.54 (0.55) respectively for osteoarthritis, chronic headache, and non-specific musculoskeletal pain. [Effect sizes here are standardised mean difference – SMD – using fixed effects; those in brackets are from the 2012 IPDM].

Overall we see an effect over sham of about 0.2 and an effect over no acupuncture of about 0.5 SMD. The question remains over whether decisions to use acupuncture should be made with the former or the latter comparison. The effect over sham excludes the context effects that naturally occur in practice, and is small – NICE guideline development groups tend to use this. The effect over no acupuncture is the pragmatic comparison, and closest to real life practice, but naturally includes different context effects for different interventions, and this is favourable to interventions such as acupuncture that might be seen as more dramatic to the patient than say a pill. It is currently impossible to separate out the different context related factors, and the compassionate touch of an acupuncture practitioner should be included in the therapeutic effect, whereas the expectation of the patient being needled perhaps should not. Sham acupuncture includes both of these and is much more effective than most other shams including placebo pills.[3]

On the whole I am a pragmatist in the complex environment of clinical practice, but I like to be a reductionist when it comes to mechanistic analysis and planning interventions. So does this huge data set allow us any further insights through purely statistical analysis? Well I am afraid that with conventional levels of statistical probability very little is revealed; however, if we are not so rigid and examine the trends with a mechanistic eye a few interesting things start to pop out.

In terms of the characteristics of acupuncture, the only factor that had a clear influence was the number of treatments, and this was only apparent in the comparison against no acupuncture. This perhaps does not come as a surprise, but it does suggest that we should be more focussed on providing enough treatment sessions and not worrying as much about other aspects of the acupuncture approach.

Many readers will know that I have a particular interest in electroacupuncture (EA), so I am keen to highlight the fact that in the more mechanistic comparison of acupuncture over sham the use of EA as a treatment characteristic had the largest effect size (0.32) and the lowest p value (p=0.14) of any characteristic studied. This does not reach the commonly adopted level of statistical probability, but equates to a 6:7 chance of being a real effect.

Image taken from http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/acupmed-2011-010036

Going back to the more pragmatic comparison of acupuncture over no acupuncture, there are a couple of interesting trends apparent. The largest was for ‘de qi attempted’, and this reached 0.74 with p=0.063. This might also suggest a dose effect, but strangely the characteristic ‘manual stimulation allowed’ actually had a moderately negative effect.

Another characteristic that approached significance in the pragmatic comparison was ‘male practitioner’ at a p value of p=0.084. The effect size associated with this was very small and negative at -0.07, but it is tempting to view this against a backdrop of mechanistic research on nocebo in pain, and suggest that male practitioners might think about channelling their more feminine sides during consultations.

There are a couple of insights that have relevance to future research. First, there was a significant difference in the effect size measured between penetrating and non-penetrating shams. There was a smaller difference between acupuncture and penetrating shams, or needling against needling, as I like to refer to this comparison. I should note that this result was not maintained when outlying trials with large effect sizes were excluded; however, I would still advise researchers to avoid testing needling against needling in clinical trials! Second was in the pragmatic comparison with no acupuncture controls. The effect size of acupuncture was significantly smaller when compared with controls that were classified as high intensity, for example a course of individualised supervised physical therapy.

The team (ATC – acupuncture trialists’ collaboration) also studied the time course of acupuncture effects by analysing the change in effect size at different time points. This seems most relevant for the pragmatic comparison against no acupuncture, but they analysed both. The effects of acupuncture held up well against no acupuncture controls with an estimated drop of only 15% of the effect after one year.

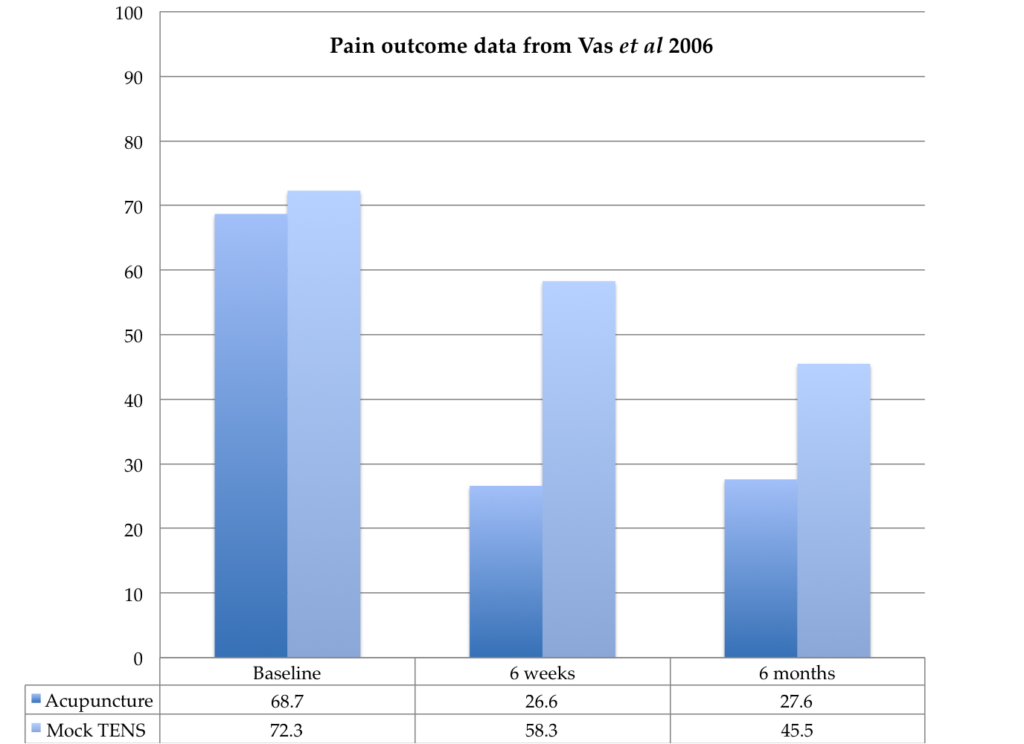

There was an estimated drop of 25% at one year in the effect of acupuncture over sham acupuncture, but heterogeneity was significant. When neck pain trials were excluded the heterogeneity disappeared, and the drop in effect size reduced to about 6%. It is difficult to imagine what this means clinically, so I investigated a little. The overall effect size for acupuncture over sham in neck pain was the most remarkable at 0.83, which sits in stark contrast to the tiny 0.17 for back pain. Neck and back pain are not the same of course, with a higher proportion of soft tissue pain being the likely reason that acupuncture has greater effects in the former. But those huge effects on neck pain seem to disappear quickly in the statistics and generate heterogeneity by contrast with small effects of a longer time course in back pain. When you look more closely you see that there are only 3 trials in neck pain, and one of them is a clear outlier.[4] I checked the original paper. It is the largest sham controlled trial in neck pain, and the control group received mock TENS. The treatment period was for 3 weeks and involved 5 treatment sessions. The mean pain score (0-100mm scale) in the acupuncture group dropped from a baseline of 68.7 to 26.6 after treatment and 27.6 after 6 months. The pain score in the control group was 72.3 at baseline, 58.3 after treatment, and 45.5 after 6 months. So you can see from these figures that the effect of acupuncture was actually maintained fully for 6 months, but the control group improved over 6 months to reduce the difference by about 50%, either by natural history or perhaps patients seeking other treatments. Just looking at the summary statistics of differences between groups gives a very different impression from the within group changes. This is one of the dangers of drawing conclusions from between group change values, without checking the within group data. We are given a false impression that the effect of acupuncture in neck pain is short-lived, when in fact it is not. The false impression comes from an improvement in the comparator, rather than a degradation of the effect in the treatment group. This change is almost certainly responsible for the statistical heterogeneity observed, and the consequent uncertainty is inappropriately directed at the acupuncture effect.

Well I think I’ll leave it there… please go and pour over the numbers in this update, it is a truly fabulous endeavour, which is giving us ever-greater clarity as the data grows, as well as more questions to debate.

References

- Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1444–53. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654

- Vickers AJ, Vertosick EA, Lewith G, et al. Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Update of an Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. J Pain Published Online First: 30 November 2017. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2017.11.005

- Meissner K, Fässler M, Rücker G, et al. Differential effectiveness of placebo treatments: a systematic review of migraine prophylaxis. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1941–51. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10391

- Vas J, Perea-Milla E, Méndez C, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for chronic uncomplicated neck pain: a randomised controlled study. Pain 2006;126:245–55. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.002

Declaration of interests

I am the salaried medical director of the British Medical Acupuncture Society (BMAS), a membership organisation and charity established to stimulate and promote the use and scientific understanding of acupuncture as part of the practice of medicine for the public benefit.

I am an associate editor for Acupuncture in Medicine.

I have a very modest private income from lecturing outside the UK, royalties from textbooks and a partnership teaching veterinary surgeons in Western veterinary acupuncture. I have no private income from clinical practice in acupuncture. My income is not directly affected by whether or not I recommend the intervention to patients or colleagues, or by whether or not it is recommended in national guidelines.

I have not chaired any NICE guideline development group with undeclared private income directly associated with the interventions under discussion. I have participated in a NICE GDG as an expert advisor discussing acupuncture.

I have used Western medical acupuncture in clinical practice following a chance observation as a medical officer in the Royal Air Force in 1989. My opinions are formed by data that spans the range of quality and reliability, much of which is in the public domain.

I have a logical mistrust of the motives of anyone who advertises an interest or hobby in being a ‘Skeptic’, as opposed to using appropriate scepticism within their primary profession, or indeed organisations that claim to promote generic ‘science’ as opposed to actually engaging in it.