Teaching for medical graduates approaching clinical exams such as the MRCP PACES exam is an anxious time. One is expected to ‘perform’ under pressure, wary of the need to elicit signs leading to potentially outlandish diagnoses. The breadth of knowledge and skills required to confidently identify CMV retinitis at one station, followed by a complicated communication scenario, with a subtle fasciculation to pick up on at the next is quite a task. It is also a task that is asked of graduate trainees in almost all specialties – the clinical portion of any membership exam is a vital stepping stone on the route to full qualification and independent practice.

I was teaching some PACES candidates this week, and played my usual game with them – what can I tell by observation of a patient and just watching their examination – that they miss. This isn’t just a mean trick – I find it helps me to concentrate on what they are doing, and in turn, helps to identify additional signs that might have been missed completely, be unknown, or simply passed off as unimportant. The gems this week included the white plaster over the bridge of the nose of a gentleman with COPD – which led to a further inspection of the surroundings – and the tell-tale NIV mask and tubing just poking out behind a bedside cabinet. The second was the white sheet of A4 stuck at eye level behind another patient’s head with the very large letters NBM written in green marker pen.

In both cases these clues to the wider diagnosis were staring the candidates in the face. However, it was only when brought to the fore that their implications for the clinical context was appreciated. So I finished the teaching session having had my fun, and the pupils might have learned a bit more about the value of careful observation, and how this can influence clinical reasoning. It was only when I got home and read this recently published paper by Dr Welsby on the neurophysiology of failed visual perceptions that I started to consider this interaction a little more objectively and how the lessons from it could be applied in other spheres.

The paper is one of those analyses of physiology and its application to everyday life that makes medical education and medical practice so enjoyable. Dr Welsby has taken 3 eye problems, and 7 brain problems, and presented them in such a way as to highlight why clinical experience – the act of examining patients, and the slow acquisition of the lived experience of using and applying knowledge over time – is so important in medical education – and suggests several reasons why he feels trainees today aren’t afforded the same opportunities to develop this experience as he was.

The paper can also give lessons for the more experienced clinicians, and perhaps could be used to highlight errors of clinical understanding on a much wider scale.

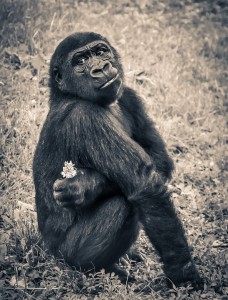

Essentially, the data our brains work with is flawed – and to compensate – our brains make it up, or completely miss the obvious because we were concentrating on something else. The paper has links to two videos which are well worth looking up – this one is my favourite. The video is a perfect demonstration of how easy it is to miss vital information, and when we apply this to the situations we work in daily – it is more impressive that we ever reach diagnoses, rather than that we sometimes get them wrong.

As one climbs the slippery pole of the medical hierarchy, it would be as well to reflect on Dr Welsby’s observations further. Clinical experience can make what seems impossible to a first year graduate, second nature to the fourth year registrar. The development of this experience allows senior clinicians to spend time thinking and working on other problems – but still with the same eyes and the same brains. Indeed – it is often successful clinicians who are chosen to lead on projects far from the clinical environment, and demand a somewhat different form of observation and synthesis of information.

As more and more clinicians are becoming involved in leadership positions, and managerial roles – those lessons learned at the bedside should not be forgotten. If the data from our health systems is flawed – the decisions we take to modify, ‘improve’ and reform them will be as flawed as those conclusions reached by a brain compensating for the incomplete information fed to it by the eyes.

Leaders from the medical profession have a duty to both remain patient with their students who miss the ‘glaringly obvious’ but must also remain vigilant for the gorillas hiding in plain sight no matter where they find themselves.