Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sport and Exercise Medicine blog series @PhysiosinSport

By Nigel Tilley @nigel_tilley

Physiotherapist on European Tour/ETPI; Team GB Golf Physio Rio 2016; European Ryder cup team physio 2016

Identifying the cause of an injury is often key to the effective assessment and management of a condition/problem. All too often practitioners jump to the ‘hands-on’ objective assessment & identification of structural issues.

Take time to stand back and speak to the player in detail to get an insight into their history and what has led them to arriving in front of you. Always remember though that first and foremost you are treating the person not the injury. As a general rule most problems we see on tour can relate to a few simple issues and is likely to be similar with most club/amateur golfers you will see in your day to day practice. Think about these things and use these questions to help you identify the problem:

1) VOLUME – Have they hit more balls recently, been practicing more, playing more? Have they been practicing a certain shot? Have they had a change in their routine? Have they started a new exercise programme or increased their workload suddenly? Have they been hitting off hard mats or suddenly gone from doing nothing for a month to hitting 300 balls a day for a week?

1) VOLUME – Have they hit more balls recently, been practicing more, playing more? Have they been practicing a certain shot? Have they had a change in their routine? Have they started a new exercise programme or increased their workload suddenly? Have they been hitting off hard mats or suddenly gone from doing nothing for a month to hitting 300 balls a day for a week?

2) TECHNIQUE – Have they changed anything in their technique recently? Grip, Swing biomechanics, equipment, footwear? Have they been pulling a cart or carrying a bag when they may normally have used a buggy.

3) ACUTE TRAUMA – have they hit a shot from thick rough, caught a tree root, forced a shot too hard, lifted something (heavy bags and equipment in/out of house and car)

4) A combination of any or all of the above. Such as a player who has recently changed shafts in their woods and made some swing changes due to poor form. But the poor form and desire to practice and ‘imbed the new swing’ changes means instead of hitting 50-100 practice balls a day they are now hitting 300 a day (a 300% increase) on tissues that are potentially not used to tolerating those loads in that intensity.

Of course there are many other potential triggers and causes of injury in golfers, but more often than not the presenting player will usually identify a specific trigger to the start of their symptoms. The solution often lies with the cause. Whilst we may direct acute treatment plans to the structures we believe are involved, the key to success is identifying the cause. More often than not education is vital to enable the player to both resolve their problem and prevent its return. We work hard on encouraging players to use practice and training logs (practice time, balls hit, number of swings, effort used, practice putting and chipping times etc) to ensure they don’t have volume and training spikes (and troughs!!). Educating players on periods of high vulnerability and injury risk, such as when they are making technique or equipment changes and to take care that they are not linked with large spikes in practice volume is hugely important.

There are 3 key areas you can get patients to work on to reduce injury potential and benefit their game.

Develop/maintain mobility in 3 key areas

The Thoracic spine

Golf requires a lot of rotation. The thoracic spine provides a lot of this rotation. If it is stiff the rotation (or rotational forces) end up going elsewhere. Often this means the Lumbar spine (which is not designed well to do this) and can lead to injury or technique faults.

The hips

Having good range of internal and external rotation in the hips is important to facilitate a full and efficient swing through correct loading and weight transference through the feet and up the chain during the golf swing. Limitations in hip rotation have been shown to be linked with increased low back pain in golfers.

The shoulders

Golf is an asymmetrical sport requiring different movements and actions from the lead and non-lead upper and lower limbs. A right handed golfer will require greater range of external rotation of the right shoulder than the left and subsequently more adduction of the left than the right during the swing. Having a good range of movement in both shoulders helps both technique and reducing excess forces to other areas of the body during the swing.

Develop stability and control through range

Flexibility is obviously important in golfers but it is equally as important to be able to safely control that movement through the range and as part of the kinetic chain. Having a stable base from which to create and transmit forces from the ground up through the kinetic chain to the hands is vital for efficient and maximal power creation & use. Being able to control and brake the forces involved in the golf swing is as important as being able to create them.

Understand a players physical capabilities and limitations

It is important for both you and the patient to have an understanding of the golf swing and what is required of the body to perform the golf swing. A player can either build a golf swing around what their body can do OR can look to change their physical limitations or improve their capabilities to fit the swing they want. Developing a good relationship with a PGA teaching professional will help you both to understand & identify swing faults & link this to your physical assessment & subsequently with your treatment & management.

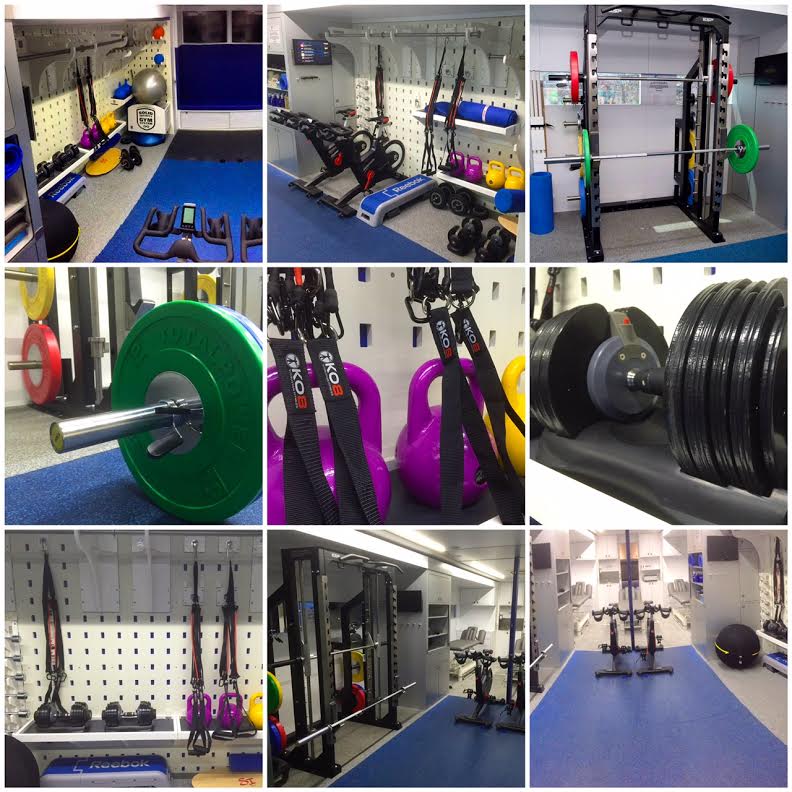

The underlying aim of what we do with players in rehabilitation and conditioning work, is ‘to make them strong, make them robust and make them stable’. Evidence really is pointing towards the use of strength and conditioning programmes and making people strong as the key tool in both injury prevention & performance enhancement. A large amount of the injuries we see in golf are tendinopathies. The immediate requirement of a player presenting to you the day before he plays an important game with an acute tendinopathy is to make sure they play if that’s what they want. Our acute management of that issue may include strappings, tapings, soft tissue techniques etc etc. But fundamental to the long term management of this is identifying the cause, ensuring the right education is given to the player and most important of all that an appropriate and structured loading programme is used for the tendon/tissues as the foundation of their management plan.

Players need to develop an underlying stable athletic foundation and to develop tissue resilience that can tolerate the forces being placed upon them. The use of strength and conditioning as part of professional golfers training is well and truly engrained and is becoming more widely used and accepted amongst amateur golfers. The golf swing requires a large mix of explosive power, strength, stability, flexibility, and athleticism. The modern day professional golfer really is now seen as an athlete. Their training reflects this. We should be encouraging all golfers we see from beginners to elite to develop that mindset and look to improve their general athleticism. As physiotherapists we are ideally placed to deal with the complex acute and chronic injuries, rehabilitation and strength and conditioning & performance needs of golfers.

References

CABRI, J., SOUSA, J.P., KOTS,M. and BARREIROS, J. (2009) Golf-related injuries: a systematic review. European Journal of Sports Science, 9(6), 353-366

EVANS, K., REFSHAUGE, K.M., ADAMS, R. and ALIPRANDI, L. (2005). Predictors of low back pain in young elite golfers: a preliminary study. Physical Therapy in Sport, 6, 122-130

FRADKIN, A.J., SHERMAN, C.A. AND FINCH, C.F. (2004). Improving golf performance with a warm up conditioning programme. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 38, 762-765

GLUCK, G.S., BENDO, J.A. and SPIVAK, J.M. (2008). The lumbar spine and low back pain in golf: a literature review of swing biomechanics and injury prevention. The Spine Journal, 8, 778-788

GOSHEGER, G., LIEM, D. and LUDWIG, K. (2003). Injuries and overuse syndromes in golf. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 31(3), 438-443

HOSEA, T.M., GATT, C.J. and CALLI N.A. (1990). Biomechanical analysis of the golfer’s back. In COCHRAN, A.J. (Editor) Science and Golf I: Proceedings of the World Scientific Congress of Golf. London: E&FN Spon, 43-48

HOSEA, T.M. and GATT, C.J. (1996). Back pain in golf. Clinical Sports Medicine, 15, 37-53

LAURENSEN, J.B., BERTELSEN, D.M. AND ANDERSON, L.B. (2014). The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injrueis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48 (11), 871-7

LINDSAY, D.M, and HORTON, J.F. (2002). Comparison of spine motion in elite golfers with and without low back pain. Journal of Sports Sciences, 20, 599-605

LINDSAY, D.M, and HORTON, J.F. (2006). Trunk rotation strength and endurance in healthy normals and elite male golfers with and without low back pain. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 1(2), 80-89

MCHARDY, A., POLLARD, H. and LUO, K. (2006). Golf injuries. Sports Medicine, 36(2), 171-187

METZ, J.P. (1999). Managing golf injuries: technique and equipment changes to aid treatment. Physician and Sports Medicine, 27, 41-58