A Tobacco Endgame for Scotland?

Katherine Smith and Jasper Been

An editorial in the November 2016 edition of Tobacco Control argued that talk about ‘tobacco endgames’ and policies that go ‘beyond ‘business as usual’ is becoming mainstream in a small number of countries, of which Scotland is one (others include New Zealand, Canada, Finland and Ireland). The race is now on to see which of these countries will be first to cross the finishing line. Attendees at a recent meeting on developing Scotland’s tobacco ‘endgame’ strategy identified three key policy priorities for a Scottish ‘tobacco endgame’: restricting availability of tobacco; pursuing a ‘polluter pays’ approach with tobacco industry profits; and introducing incentives for disadvantaged smokers to quit.

Tobacco Control in Scotland

Scotland is one of many countries that have taken major steps to reduce tobacco use, and related health harms, in recent decades. Having been a leader in the establishment of smokefree public places, Scotland’s current tobacco control strategy, launched in 2013, was bold in its commitment to Scotland becoming ‘smokefree’ (defined as adult smoking rates of 5% or less) by 2034. If this ambitious aim is to be achieved, it will require radical policy initiatives, consistent with recent proposals for tobacco ‘endgame’ scenarios. To date, however, there has been limited discussion of what specific policies ought to be pursued in Scotland to achieve the 2034 ‘smokefree’ goal.

In order to start addressing this gap, on 24th October 2016, an Usher Institute of Population Health Sciences and Informatics/ESRC supported seminar took place in Edinburgh in which researchers, advocates, policymakers and practitioners came together to discuss what a tobacco ‘endgame’ for Scotland might look like. The session involved multiple presentations and ‘pitches’ for policy proposals from a range of experts. Everyone present then had the opportunity to put forward potential policy proposals before collectively voting to identify those with greatest support.

What is a ‘tobacco endgame’?

The concept of ‘tobacco endgames’ is an analogy taken from the game of chess, the idea being that when you’ve got fewer pieces on the board (towards the end of the game), you need to change tactics to win. In public health terms, talking about tobacco endgames marks an important shift in focus towards ‘seeking to end the tobacco epidemic, rather than control it’. Since ‘the essence of the endgame requires thinking outside the box’ the kinds of proposals that are put forward as potential tobacco endgame strategies are often rather more radical than those that we have seen implemented to date.

A recent review of tobacco endgame proposals identified a four broad potential strategies. Some focused on the product itself, others on restrictions for users, while others focused on the market and structural issues:

- Product– make cigarettes less addictive or appealing, or implement strategies to displace combustible cigarettes with the less harmful alternative of e-cigarettes.

- Users – restrict access through smokers’ licences or prescriptions for purchasing tobacco, as well as incrementally increase the legal age of purchase to gradually phase out tobacco.

- Market mechanisms – reduce retail availability, ban combustible tobacco products, make non-combustible nicotine products easier to purchase than combustibles, restrict manufacture and importation of products, price caps.

- Structural – create a new tobacco control agency, create a regulated market, state takeover of tobacco companies, introduce a performance-based regulation system.

Does Scotland need a ‘tobacco endgame’?

Devolution afforded Scotland a ‘window of opportunity’ in addressing public health challenges. The Scottish Government has implemented a range of tobacco control policies including banning smoking in enclosed public spaces, outlawing vending machines and point-of-sale displays, and, most recently, banning smoking in cars carrying children. While most of these policies have now been implemented in other parts of the UK, Scotland has demonstrated clear public health leadership in this area and its commitment to becoming ‘smokefree’ (i.e. adult smoking prevalence of 5% or less) by 2034 indicates a desire to continue leading on tobacco control.

Reflecting these developments, smoking rates are coming down and we now have the lowest rates of smoking among young people and adults that Scotland has seen in decades. There has also been a significant decrease in the proportion of children exposed to second-hand smoke (from 11% in 2014 to 6% in 2015), following a successful government campaign on this topic. However, the latest data suggest around 21% of Scotland’s population smoke, a figure that is still higher than other parts of the UK. Also, while smoking prevalence is decreasing across all social groups in Scotland, a marked social gradient in smoking rates still exists. Moreover, to achieve the endgame targets we will need a much more rapid decline in smoking amongst the most disadvantaged compared to more affluent groups.

All of this poses some significant challenges. Most pressing is how to reduce smoking in Scotland’s poorest and most disadvantaged communities (including, for example, those experiencing mental ill-health) while avoiding the stigmatisation of those who find it most difficult to quit smoking (and evidence here is limited). Increasing the price of tobacco is the only specific intervention consistently shown to have a positive equity effect in terms of smoking prevalence. Yet, while traditional tobacco taxes are progressive in health terms by promoting cessation, they are regressive in economic terms for those who don’t quit, and such taxes can exacerbate the stresses and material impacts of life on a low income. These broader effects have only recently begun to be studied and have not yet been explored in a Scottish context.

What kinds of approaches were suggested for Scotland?

Having had an overview of the ‘endgame’ options outlined above, four broad policy pitches for Scottish approaches were put forward at the event, before participants went on to suggest four broad and interlinked policy proposals:

- Re-orientating tobacco control to take a broader social determinants approach, focusing on addressing the underlying drivers of tobacco use, especially in poorer communities. This involves thinking about some of the upstream drivers of tobacco use, including the efforts of the tobacco industry. Evidence indicates that tobacco control in Scotland, as in many other contexts, is now overwhelmingly an inequalities issue and should therefore be addressed as such.

- Framing tobacco control as a human rights issue (especially for children) on the basis of the right to health and associated rights. Scotland is (usually via the UK) party to a range of international and regional human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which means that the Scottish government can use obligations set out in these legal documents to help make the case for further tobacco control measures, especially where these protect children from tobacco use and exposure.

- Measures to reduce the local provision of tobacco retailing, which is currently ubiquitous across Scotland. Strong research evidence demonstrates the links between neighbourhood density of availability and smoking prevalence. Availability is also part of the inequalities story since the density of tobacco outlets in Scotland varies geographically, with deprived neighbourhoods having about 77% more places to buy tobacco than more affluent areas. So environments are currently heavily loaded against poorer communities and this needs to be addressed. Scenario modelling in New Zealand looked at the impacts of reducing density around schools, removing licenses and an overall availability reduction of 95%. This work suggests positive impacts in terms of raising prices of tobacco products and reducing smoking prevalence. We need to do similar work in Scotland.

- Strengthening and extending regulation of tobacco as an industrial epidemic. While measures have been taken to prevent the tobacco industry influencing health policy, its expanding interest in new technologies such as e-cigarettes potentially re-opens the policy door to tobacco industry interests. For some, this might be seen as offering tobacco industry interests a ‘way out’ through harm reduction, a route Philip Morris International has presented itself as considering. In contrast, this pitch suggested a need to continue to focus on the role of the tobacco industry, and for regulation to be increasingly shaped by the ‘polluter pays’ principle. This could form part of a wider approach to regulating producers of unhealthy commodities, including alcohol, as modifiable structural determinants of health.

Running across several of the pitches, there was also a plea to work collaboratively with those communities most negatively affected by tobacco use and associated health inequalities. This could help inform policy debates about what approaches are publicly supported and reduce the risk of stigmatising poorer communities.

What specific policies were suggested and which were most popular?

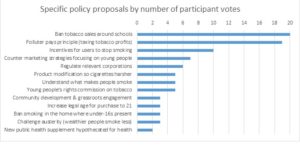

After hearing the pitches, the 37 participants formed small groups to consider specific proposals for a tobacco endgame in Scotland. Each group’s proposals were collated and similar suggestions combined. This resulted in 14 distinct policy proposals that were voted on anonymously by the participants (each participant had three votes). The bar chart below demonstrates that the three most popular strategies involve: restricting availability of tobacco around schools, pursuing a ‘polluter pays’ approach with tobacco industry profits (and investing revenue raised for health) and introducing incentives for disadvantaged smokers to quit (a policy that has already been successfully trialled for pregnant women in the West of Scotland but which is currently not in place).

What next?

Overall, participants at the seminar seemed broadly supportive of the idea that Scotland now needs to develop a clearer conception of a tobacco endgame. Admittedly this only reflects the views of an invited group of health professionals (researchers, practitioners, policymakers and advocates) whose concerns focus on improving public health and reducing health inequalities. For others, the idea of a tobacco endgame might seem at odds with a liberal policy environment, or else simply feel impractical. Nonetheless, if the Scottish Government is serious about achieving a smokefree Scotland by 2034 then we need to advance discussion about potential ways forward. This becomes pressing given that Scotland’s current tobacco control strategy ends in 2018, with endgame thinking having an opportunity to shape development of a new strategy. The suggestions emerging from this event represent a further contribution, as do those from bigger events such as the 2016 Scottish Smoking Cessation Conference, but discussions also need to become far broader, public, and inclusive. Given the risks of stigmatising smokers, particularly those living in more deprived communities, it will be particularly important to engage these groups in such discussions and this is a topic that researchers in GRIT (the Group for Research on Inequalities and Tobacco) will be pursuing.

Katherine Smith is a Reader in the Global Public Health Unit and member of GRIT (Group for Research on Inequities and Tobacco at the University of Edinburgh. Jasper Been is a member of the Usher Institute of Population Health Sciences and Informatics at the University of Edinburgh and Erasmus MC-Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks are due to everyone who participated in the 24th October 2016 seminar and to Ash Scotland and GRIT (the Group for Research on Inequalities and Tobacco), the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government, the Farr Institute and the Usher Institute at the University of Edinburgh, for supporting this event. We also acknowledge ESRC funding for this event via a seminar series grant (‘Tobacco and Alcohol: Policy challenges for public and global health’, Grant No. ES/L001284/1). Finally, we would like to thank Lynn Morrice and Rebecca Campbell for organising practical aspects of the event.