Kelley Lee

Associate Fellow, Centre on Global Health Security, Chatham House

In July 2012, Japan Tobacco International (JTI) launched a campaign against the UK Department of Health’s consultation on the plain packaging of tobacco products. The UK is one of JTI’s top five markets worldwide and there are fears that the UK, and potentially other European Union members, will follow the Australian decision to adopt plain packaging.

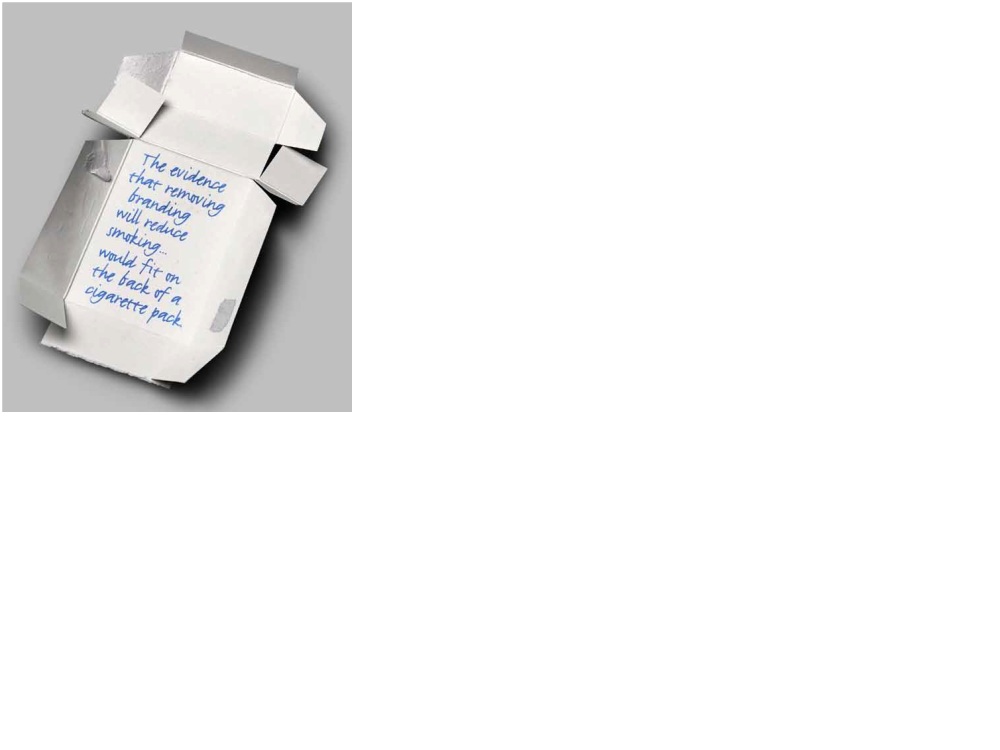

JTI’s campaign has so far been undertaken in two phases. The first phase claimed that the consultation process was ‘a series of individually flawed consumer surveys’, supported by “a panel of ‘experts’ and their subjective views on what smokers might do”. Plain packaging was described as having “no evidence” to support it and, in an accompanying press release, JTI UK Managing Director Martin Southgate hoped that “the Department of Health will re-think its approach and common sense will prevail”. The second phase of the campaign, rolled out in September 2012, focused on counterfeiting, and the industry’s predicted impact on the livelihoods of local small businesses and the national economy. In full-page advertisements, cartoon-like images of ‘standardised’ cigarette packets were used to raise concern about how easily they would be copied.

JTI’s criticism of the lack of evidence behind plain packaging, citing the importance of ‘evidence-based policy’, is ironic given the industry’s own track record on the undermining of scientific evidence and policy processes. This latest campaign narrows the scope of acceptable evidence to a particular type of policy evaluation (post implementation). Given that Australia will be the first country to adopt plain packaging, the type of evidence demanded is not yet possible. Importantly, the campaign continues a tradition by the industry of ignoring substantial bodies of unfavourable evidence. It is well-known, for example, that consumers respond directly to packaging, particularly young people who tend to have a stronger response to colour, logos and images on cigarette packs. Other evidence shows that plain packaging enhances the impact of health warnings.

When applied to the counterfeiting issue, JTI’s call for evidence-based policy is shown to be even more tenuous. The company speculates that “standardising packs will make them even easier to fake and cost taxpayers millions more than the £3billion lost in unpaid duty last year.” If assessed by the company’s own standard of proof (i.e. evidence following policy implementation), this claim hardly stands up. More importantly, there is substantial evidence suggesting that the illicit cigarette trade is supported by tobacco companies themselves. Plain packets will still require large pictorial health warnings and covert security markings, making them as difficult to counterfeit as branded packs. None of this, however, is mentioned in JTI’s campaign. Its efforts to cloud public debate on the issue are plain.