by Carys Durie and Sioned Edwards

4th year Medical Students, Cardiff University

The 2017 Hay Festival of Literature and Arts set in the Welsh town of Hay-on-Wye, celebrated its 30th anniversary this year. Speakers included the likes of Tracey Emin, Bernie Sanders, Stephen Fry and Ed Balls. Pianist James Rhodes closed the first weekend with a Bach recital, dedicated to the people of Manchester after the terror attack that left many dead. These recent tragic news events gave particular poignancy and context to a discussion on grief, which formed a central theme of one particular literary event, which we have described below.

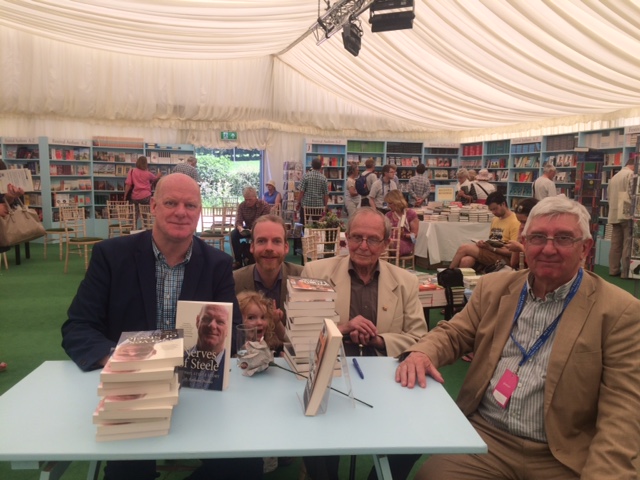

We attended a packed, sweltering Starlight tent, where an apparently disparate group of speakers took to the stage: Welshman George Brinley Evans, ex-miner and now recognized painter, sculptor and published author; Phil Steele, former Welsh rugby player and current BBC sports broadcaster; and Dr. Mark Taubert, Consultant Physician and Clinical Director for Palliative Care at Velindre Cancer Centre in Cardiff. The discussion entitled ‘Before the End – Telling Your Story In Time’ was chaired by Professor Hywel Francis, chair of Byw Nawr/Live Now, the coalition dedicated to raising awareness of dying, death and bereavement.

Male grief remains a subject that is not talked about in our society. Bereavement and grief were the central themes of the day’s talk. Phil Steele and George Brinley Evans discussed how bereavement had encouraged them to tell their own stories, despite many setbacks. Steele’s autobiography Nerves of Steele, his writing debut, maps out his life from his beginning as an ‘Ely boy’ in Cardiff, to the successful and entertaining broadcaster he is today. Steele was a professional rugby player with Newport RFC, when he suffered his first bout of depression: aged just 23, he had sustained an injury that put paid to his promising career. Steele went on to endure the loss of four family members, including his wife, Liz, in 2009. Steele put it as having five losses in his life, four of them being bereavements, the fifth loss being his rugby playing career. He pointed out that grief or bereavement does not necessarily entail the death of a person or loved one, but can also be that of a bodily function or role. Thus grief can take many patterns and forms. He described how he did not find talking about it difficult, but that others avoided these conversations, and he sensed an awkwardness in discussing grief and depression in his wider circles.

Dr. Mark Taubert explained the different forms that grief can take. While most of us are aware of the stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance – psychologists now also accept different types of grief, intuitive and instrumental, as two ends of a spectrum. Intuitive grief encompasses open expression and emotions, said Dr Taubert, describing it as a grief in which ‘expression mirrors feelings’. People veering more towards this form of grief, often talk about their feelings, and share their emotions and experiences with others. By contrast, in instrumental grief, grievers are less willing to share their thoughts and instead go through a period of quiet and inward processing, while they come to terms with their loss. Dr. Taubert described instrumental grief as being ‘action orientated’, with people finding comfort through channeling their energy into a project, and often immersing themselves in work. These two types of grief sometimes fit the perceived ‘gender stereotypes’; some people assume that women are more open (intuitive) grievers, and that men are more inward instrumental grievers, ‘disappearing to their sheds’ –some laughter and nods from the audience here-. Dr Taubert explained that these gender stereotypes are not always correct and he observed many female instrumental grievers and male intuitive grievers, sometimes oscillating between these two types of grief. Grief experiences are influenced by more than fourty distinct factors, making each grief experience, as Taubert put it, ‘as unique as a fingerprint’.

George Brinley Evans described growing up at a time when grief was simply not spoken about and “you certainly didn’t show it”. When he was a miner, three British coal miners were killed every day and children were dying of diphtheria; it was a time when men and women alike were expected to “carry on as normal”, as the iconic war time poster dictated. He described the way that, in times of grief, men would “go to work and busy themselves” rather than grieving with their family and talking about it. Men didn’t cry. He remembered the 1930’s when funerals were “gentlemen only”: women and children were kept at home to grieve in private, while the men in the community would attend the funeral on their behalf.

Evans’ most recent novel, ‘When I Came Home‘, recounts conversations from 60 years ago; these memories deal with births and deaths, struggles and triumphs, memories he has vividly captured. Reflecting on this latest work, George Brinley Evans stressed the importance of being able to get his story down on paper: “When you write, it’s just you and the page; there are no conflicts of characters”. For him, the best way to capture his story and relay it to loved ones was through writing it.

When talking about his experience of depression, Phil Steele – who described receiving comments such as “You of all people with depression Steeley!” and “How could it happen to you?!” – raised the question of the language we use when talking to a person facing a loss or struggling with mental health problems. There was too much ‘fighting talk’ and phrases such as “battling depression” or “you’re going to beat this”. This was seconded by Dr Taubert, who observes such war metaphors and battle language in everyday practice at the hospital, and who’s patients have told him it can be damaging and disempowering. He suggested that people actually feel let down by these expressions since, ultimately, we all ‘lose the battle’, if we chose to use this patois. The panel felt that it should not be about fighting depression or battling with grief, but learning to accept it. More on the language of grief and loss can be found in an article by Dr Taubert entitled “War and Peace in Cancer” in the Huffington Post. He has also made it the central theme in a recent Ted Talk.

There was discussion about the role of digital media in raising the issue of grief, but also offering new ways of collecting experiences and memories for future generations. This was not a session which finished with all answers tied up neatly at the end. By way of underlining the fact that this should be a constant and ongoing discussion for everyone, Professor Hywel Francis posed a further question for his speakers and audience. He simply asked a series of questions “What could you do, to help discussions about grief? What could you do to help a person come to terms with a loss or faced with a mental disorder? What could you do to change your perceptions of grief and how we grieve? What could you do to help a loved one share their feelings and experiences, and help them to tell their story before the end?” All salutary questions and hugely important in terms of raising consciousness of issues which inevitably affect us all.

As a society, we can at times be judgmental about the way people grieve and how we feel people ought to respond to loss. Discussions like this one at Hay focused attention on bringing death and grief into the everyday here and now and on the need to open people’s eyes to the complexity and uniqueness of bereavement. Bringing such things into the open creates the possibility of continuing bonds and encouraging resilience in those that are left behind.