Our film and media correspondent, Khalid Ali, reviews Sheikh Jackson (Egypt 2017), directed by Amr Salama

Showing at the London Film Festival (LFF), 5, 7, and 12th October 2017

Amr Salama is no stranger to the LFF; his films Asmaa, and Excuse My French showed at the LFF in 2011 and 2014 respectively to great critical and audience reception. In Asmaa, he challenged the unprofessional attitude of some doctors in denying a woman living with HIV a gall bladder operation for fear of contracting the disease. Secular confrontation in Egypt and its impact on children was the theme of Excuse My French. In his latest film Sheikh Jackson, Salama throws his net wider to tackle a multitude of issues from father-son relationships, to midlife crisis, to religion and mortality. The central character (played by Ahmad Alfishawy) is a middle aged Islamist with extremist beliefs who remains nameless for most of the film. He denounces music, dance and television as ‘the devil’s weapons of temptation’. As a child he was a totally different character; a hapless kid daydreaming of a ‘romantic liaison’ with the school’s sweetheart, and at night secretly idolising Michael Jackson.

The day the ‘King of Pop’ died in 2009 becomes a turning point, when as a responsible adult and father he begins to question his religious and moral convictions. Auditory and visual hallucinations start to dominate his life. Struggling with lack of sleep, anhedonia, and ‘inability to cry’, he seeks psychiatrist help. On the ‘psychiatrist couch’, he reflects on his childhood and adolescence traumas, his volatile relationship with his abusive father, and the loss of his kind mother who died young. Through these flashbacks, we see his transformation from a fun-loving teenager ‘moon-walking’ to Michael Jackson’s ‘Dangerous’ tune to a radicalised preacher.

The storyline is built like a jigsaw where the pieces of the puzzle are tantalisingly told which demands repeated viewings to appreciate its significance and complexity. A fascination with psychoanalysis runs throughout the film in its exploration of several mental health ailments; from ‘parental alienation syndrome’ to ‘separation anxiety disorders’, to ‘celebrity worship syndrome’ and depression. Cognitive behaviour therapy, aka the talking therapy, holds the key in helping the protagonist to come to terms with his identity crisis.

A recent study from the British Police suggests that depression and loneliness are common traits in radical extremists. Ahmad Alfishawy as the marginalised fundamentalist embodies those emotions of social isolation and hopelessness in a nuanced and heartfelt performance. Another stand-out performance comes from Maged El Kedwany as the abusive self-centred father.

There are several historical, cultural, and mystical cult references that run throughout the narrative for the discerning viewer. Inability to cry as a metaphor for joyless existence, with tears signifying life and reincarnation has its roots in the story of Isis, the Egyptian Goddess whose floods of tears brought life back to her beloved brother and husband Osiris.

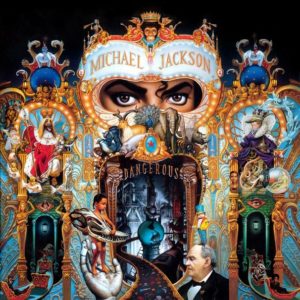

The choice of Michael Jackson’s CD ‘Dangerous’ (1991) with its enigmatic cover provides a myriad of interpretations connecting the film’s troubled Egyptian hero to Michael Jackson. The album cover, designed by Mark Ryden features the notorious British author, poet and occultist Aleister Crowley, and hints towards ‘worshipping Satan’ as a means to get to the top of the music industry. It is interesting to note that Aleister Crowley, founder of the Thelema cult, wrote The Book of the Law describing those ‘satanic beliefs’ in 1904 when he was in Egypt. In some scenes in the film, music is referred to as ‘the psalms of Satan’. The eyes of Michael Jackson staring from behind a mask, in the album cover, has its counterpart in the protagonist’s inability to cry. The chaotic circus represents loss of control and faltering grip on reality that the film’s lead is going through.

Salama challenges the reasons why ‘extremists’ denounce art and culture in today’s society, and makes his own ideologies clearly known. Music, dance and art are crucial to our mental health and well-being by providing an outlet for self expression and creativity whatever our religious or cultural backgrounds are. In a poignant scene, the viewer is reminded of two classic scenes from The Lives of Others (2006) , and The Shawshank Redemption (1994) . In those iconic scenes, Gerd Wiesler and Andy Dufrense connect meaningfully with music and its magical ability to transform the lives of the most isolated and troubled souls. Finding balance and equilibrium in our world today is a formidable challenge, however our compass in that eternal search lies in liberating our minds and senses.

The film occasionally loses its focus by trying to juggle several thought-provoking subjects; some viewers might find it hard to follow simultaneously three stories in different time lines. It is also a real shame that Michael Jackson’s original music does not feature in the film; the spell of those iconic melodies and their legacy are hard to recreate with a new music score imitating such popular tunes. Still, Sheikh Jackson remains an important film to watch; persevere with it till the finale where the name of the troubled hero will be revealed, and his soul-searching journey comes to an end. You will be rewarded with a cinematic moment that will stay under your skin for a long time to come.