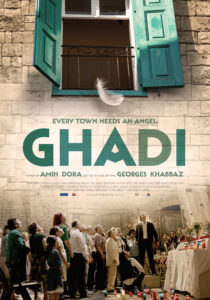

Music overcoming disability – Ghadi, Lebanon, 2013, directed by Amin Dora

Reviewed by Dr Reem Gaafar, a Sudanese doctor, writer, filmmaker and graphic designer

A special screening will take place at the Polish Cultural Centre, 238 King Street, Hammersmith, London W6 0RF, Sapphire Room, 2nd Floor, at 8pm Friday 3rd June 2016. To book tickets khalid.ali@bsuh.nhs.uk

To buy copies of the film, please email eskaff@thetalkies.com

Ghadi, a 2013 film from Lebanon tells a poignant story: In a small town called Al Mshakal, there lived a young boy named Leba. Leba had a stutter, and was subjected to bullying and humiliation from his schoolmates, until a mysterious music teacher, Mr. Fawzi moved into town with his piano as well as nightly Mozart recitals. Using music lessons and improvised speech therapy, Mr. Fawzi helped Leba grow out of his stutter. Years later, Leba becomes a music teacher himself. His music attracts his childhood crush Lara into his classroom, and one Sunday afternoon, into his life. Their happy marriage is crowned with two beautiful daughters, but the family’s blissful life is disturbed by the obtrusive local community urging Leba and Lara to try for a baby son. The so-called caring community lived on gossip and backbiting with dishonesty flowing through the cobbled streets like a dark, murky river.

Eventually, a baby boy is conceived, but to the couple’s distress he is expected to be born with special needs. Leba has serious concerns: should the child be born or not? Is it fair to bring such a child into the world? He seeks advice from Mr. Fawzi, his childhood teacher and friend. Mortified by Leba’s doubts, Mr. Fawzi advises him to name the child immediately, to give him a presence, an existence, and the right to live. A few months later, Ghadi is born with Trisomy 21 (Down’s syndrome) becoming the most handsome boy in the neighborhood.

In today’s world of modern technology and advanced medicine, it has become relatively common for a couple to face the impending reality of bringing a ‘different’ child into the world. Basic ultrasound, amniocentesis and chorionic villous sampling can detect as early as 10 weeks a child with congenital and chromosomal anomalies, genetic disorders of metabolism, and various growth abnormalities. First trimester screening for Down’s syndrome has become routine in the developed world (Huang et al, 2015), and screening for anomalies at 18-20 weeks is becoming regular practice in the developing world. The course of action that follows the discovery of an aberration, however, is not at all globally agreed upon.

Many factors – religious, legal, educational, social and others influence the expecting couples’ decision to undertake the screening procedures in the first place, and to continue or terminate the pregnancy. Studies suggest that health professionals are more likely to lean towards termination of abnormal pregnancies than the general lay person (Drake, Reid and Marteau, 1996, Norup, M, 1998), and that a third of women who have a sibling with Down’s syndrome would consider termination if their prenatal screening proved they were carrying a child with chromosomal aneuploidy (Bryant, Hewison and Green, 2004). However, some individuals remain uncertain about terminating a fetus with Down’s syndrome compared to other conditions such as spina bifida and hemophilia (Bell and Stoneman, 2000). Some parents and/or health professionals think it is justified to not provide children with Downs’ syndrome the necessary medical and social care they need. Some families hand over the responsibility of these children’s care to public health systems through adoption (Julian-Reyniar et al, 1995).

On the other hand, advances in medicine and technology are allowing everyone, including the disabled, to live longer and healthier lives. Disability activists are now calling for women to resist the pressure to abort a disabled fetus, believing that such acts oppress the rights of the disabled, as well as adversely affecting all women (Saxton, M. and Davis, L., 2013).

While prenatal screening is being increasingly offered in the Middle East, the attitudes of both lay people and doctors are still unknown concerning abortion in general, and aborting a potentially-disabled fetus in particular. It is to be expected that these attitudes are based on cultural and religious beliefs and the laws that govern them. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is predominantly Muslim, and the local laws rely heavily on the different interpretations of Islamic ruling in this matter, as well as on those laws inherited from colonial times. Abortion laws range from liberal to very restrictive, but the position of selective abortion relating to Down’s syndrome is not at all clear. Only Tunisia and Turkey have laws that allow abortion without restriction based on underlying reason (Dabash, R and Roudi-Fahmi, F, 2008, Hessini, L, 2007).

Ghadi spends his days and nights at the family’s home singing his peculiar songs, irritating the neighbourhood even more than Mr. Fawzi’s Mozart recitals used to. Eventually, Leba is faced with an ultimatum: either to send Ghadi to a specialist institution, or face the prospect of eviction with his family from their hometown. Desperate for a way out, Leba, helped by the village outcasts, succeeds in conjuring an elaborate plan to convince everyone that Ghadi is an ‘angel’ who can grant local people their wishes and punish them for their sins. In an unexpected twist of events, the townsfolk transform into honest, law-abiding citizens in fear of the wrath of ‘Ghadi, the angel’.

The film suggests that in spite of Leba’s initial apprehension and the community’s rejection of Ghadi, the pro-life decision for children with special needs ultimately turns out to be the correct and rewarding decision for all. Down’s syndrome is now officially recognized globally with a whole week dedicated annually to increasing awareness.

Special thanks to Amin Dora and Elyssa Skaff for kindly facilitating this review.

Address for correspondence: gaafar.reem@outlook.com

References

Bell, M. and Stoneman, Z. (2000). Reactions to Prenatal Testing: Reflection of Religiosity and Attitudes Toward Abortion and People With Disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation: January 2000, Vol. 105, No. 1, pp. 1-13.

Bryant, L., Hewison, JD and Green, M., (2005). Attitudes towards prenatal diagnosis and termination in women who have a sibling with Down’s syndrome. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, Volume 23, Issue 2, 2005, pg. 181 – 198, DOI: 10.1080/02646830500129214

Dabash, R and Roudi-Fahmi, F., (2008). Abortion in the Middle East and North Africa. Population Reference Bureau, USA. Online, available at

http://gynuity.org/resources/read/abortion-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-en/

Drake, H., Reid, M. and Marteau, T. (1996). Attitudes towards termination for fetal abnormality: comparisons in three European countries. Clinical Genetics, 49: 134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1996.tb03272.x

Hessini, L., 2007. Abortion and Islam: policies and practice in the Middle-East and North Africa. Reproductive Health Matters, vol. 15, no. 29, pg. 74-84

Huang, T., Dennis, A., Meschino, W., Rashid, S., Mak-Tam, E. and Cuckle, H., (2015). First trimester screening for Down syndrome using nuchal translucency, maternal serum pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, free-β human chorionic gonadotrophin, placental growth factor, and α-fetoprotein. Prenatal Diagnosis, Vol 35, pg. 709 – 716, DOI: 10.1002/pd.4597

Julian-Reynier, C., Aurran, Y., Dumaret, A., Maron, A., Chabal, F. Giraud, F. and Aymé S, 1995. Attitudes towards Down’s syndrome: follow up of a cohort of 280 cases. J Med Genet 1995;32:597-599 doi:10.1136/jmg.32.8.597

Norup, M. (1998), Attitudes towards abortion among physicians working at obstetrical and paediatric departments in Denmark. Prenat. Diagn., 18: 273–280. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199803)18:3<273::AID-PD256>3.0.CO;2-5

Saxton, M. and Davis, L., (2013). Disability rights and selective abortion. Chapter 7: The disability studies reader, pg. 87 – 99. 4th edition, Routledge, New York USA