Reviewed by Steven Kenny

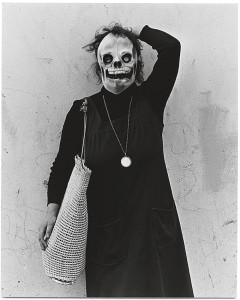

Jo Spence, The Final Project, 1991–92. © The Estate of Jo Spence. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London.

Jo Spence was a pioneering figure within the realms of photographic discourse, image based political activism and the application of photography as a therapeutic tool. From the early 1970s Spence worked within photographic collaborative modes, first with Terry Dennett to form the Photography Workshop Ltd and later co-establishing the Hackey Flashers and Polysnappers. Spence’s later works turned inwards, directing the gaze towards the body, and specifically her ill/diseased body, and her battles with breast cancer. Such works became charged with a context of survival and transgression, this photography ‘a response to her treatment by the medical establishment and her attempt to navigate its authority through alternative therapies’ (Vasey, s.d).

The Final Project is the last documentation of Jo Spence’s work. A book of eerie beauty and macabre investigation, The Final Project stands as the artist’s last photographic output before her death as a result of leukaemia in 1992. The resultant images stand as a testament of confrontation, expectation and spiritual transcendence. Within the book’s inside flap a small quote from Spence provokes thought, ‘“How do you make leukaemia visible? Well, how do you? It’s an impossibility”’. This quote particularly hit home as my uncle also died as a result of leukaemia. At the time I did not understand the condition, only hurt by its ramifications, never truly knowing its pathological effects nor its ability to conceptually redefine the body as sick and the other. The Final Project is a particularly significant book as it highlights the importance of representing the ill body, one that is affected by the invisible and the hidden. Spence’s work depicts a process of struggle, humour and later acceptance during her illness experience.

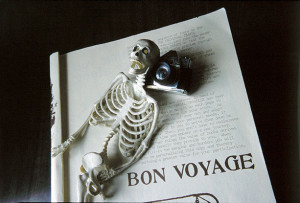

At the end of her career, Spence became too unwell to travel and work. However, the limitations imposed by physical frailty did not stop her determined and strong work ethic. During this time, Spence trawled through her vast photographic archive to create further visual documents from those that make reference to mystic realism. Her output became imbued with the anticipation of death, and as a result the imagery decoded visual artefacts of the iconography of the dead through the layering of two slides, one on top of the other. These objects, once photographed, became talismans of spiritual power, and as Louisa Lee (2013:11) comments, ‘allegorical props for representation’. The skull features consistently throughout The Final Project; in one photograph it engulfs the frame, in another the skull is depicted as a mask to be worn (see front cover above), and in others it appears to be used as an object to physically represent the artist’s presence. The skull is now a contemporary icon, a product of fascination that can be seen across various artistic forms and cultural practices. Her archive takes on its own being, and as a result comes to physically stand in for the artist; her visual history creating new histories that can be once again archived. The photographic montage can thus be seen within the book as a form of catharsis, the constructed image an item of therapeutic power with the ability to define new identities.

Jo Spence, The Final Project, 1991–92. © The Estate of Jo Spence. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London.

On examining the work throughout the book, one might conclude that such images may be associated with Sigmund Freud’s theory on the death drive, which explored the apparent conflict between not having knowledge of our inevitable experience of death, and the resurgent repetition of unconscious exploration into gaining such insight. As suggested by the author Maria Walsh (2012), ‘Art can be tied to either of these strands, depending on whether an artwork is on the side of binding the chaotic force of the death drive or repeating its disruptive impulses’. Spence’s work within this series seems to lie preciously between the two, with such works seen as a taming or normalisation of death from acceptance of its iconography, yet becoming entangled within a mode of repetition as images are repeated and spliced with others to form new variations. It must be stressed, however, that such work is not at all chaotic, but is instead peaceful, dreamlike and calmly ambivalent. Thus it becomes difficult to categorise Spence’s final work, also true for her entire lifetime output, which confidently straddles various modes of representation and classification. The work is enigmatic, a photographic force in representing the invisible and redefining the ill body in transgression.

Humour has served as an important emotional device throughout Spence’s career and artistic work, and again is of great importance within The Final Project. Melancholy juxtaposed with laughter creates a darkly humoured conflict, the work’s methodology resembling the artist’s perseverance in contrast to her deteriorating health. Humour is utilised as a concept not only to promote positivism, but also to punctuate the isolation caused by disease. The skull as motif is disseminated as a cryptic symbol of both death itself and of its subsequent control over it. Spence does not trivialise death but instead attempts to seek some comfort and emotional release from its seriousness. As Sheri Klein (2007) suggests, ‘The intent of humour is to overcome the tragic impulse so that life is bearable’. Spence does not give up, nor does she stop creating. Instead, the artist utilises photography as a method to pictorially represent her own transition. The work serves as a form of therapy, much in the same manner as her previous phototherapy work represented her battle with breast cancer. One element has importantly changed, however. Spence now begins to absent herself from the frame, and instead presents her physical self through her previous constructed representations — a body not yet affected by the disease, a historical body that can be manipulated and freely controlled.

How do we come to terms with death? Perhaps more importantly, can we ever come to terms with our own limited physicality? I believe that these are deeply subjective, complex and quite probably impossible questions to answer, but as Klein (2007) suggests ‘Humour from art, as experienced through smiling and laughing, can be a catalyst for personal and collective healing, wellbeing and improved psychological health’. From reviewing the work of Spence, one could conclude that laughter and the ability to poke fun at death might be more therapeutic than resorting to a grief state that solely focuses on inexorable loss.

Jo Spence, The Final Project, 1991–92. © The Estate of Jo Spence. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery, London.

Lee, Louisa (ed.) (2013) Jo Spence: The Final Project. London: Ridinghouse.

References

Klein, Sheri (2007) Art and Laughter [Scribd Edition] From: www.scribd.com (Accessed on 13.01.15)

Vasey, George (s.d) Jo Spence – Biography. At: http://www.jospence.org/biography (Accessed on 13.01.15)

Walsh, Maria (2012) Art and Psychoanalysis [Scribd Edition] From: www.scribd.com (Accessed on 13.01.15)