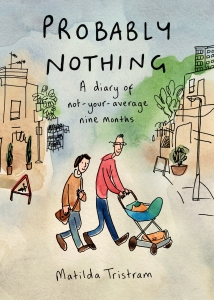

Probably Nothing: A diary of not-your-average nine months

Matilda Tristram

Reviewed by Nicola Streeten

Aged 31 and four months pregnant, Matilda Tristram was presented with an agonising dilemma following a diagnosis of stage three bowel cancer. In May 2013, The Guardian newspaper featured an interview with Matilda Tristram (Williams, 2014). It included an excerpt from what was to become her graphic memoir. The examples were small comic panels she drew as a way of telling people she knew what she was going through. The dilemma she faced was this: if she had chemotherapy it may save her life but may also cause miscarriage or damage to the baby. If she aborted the pregnancy and had chemotherapy, it may leave her infertile. If she didn’t have the cancer treatment she would be likely to die. My memory of The Guardian article is that the drawings were in black and white, which they weren’t. However, the situation was rather colourless.

Fast forward to 2014. Penguin has published Tristram’s full story, Probably Nothing: A diary of not-your-average nine months in full colour (Tristram, 2014). Tristram is well and glowing; the baby is alive and thriving. Curiosity lures the reader. How did she make the decision? Was it all straightforward? And the biggest question, how did she mentally and physically deal with such a rollercoaster ride through adversity? For me, the curiosity comes from knowing that a similar thing could happen to any of us or our loved ones and we may learn how to respond from reading Matilda Tristram’s diary. This is the pull of the graphic memoir, especially around subjects of illness and/or trauma. The drawing style Tristram has used is easy on the eye, encouraging the reader to engage directly with the narrative. Her deceptively simple drawings convey immediacy, as if it is happening right now. It is a diary, as the title asserts, and the drawings call to mind the styles of other graphic memoirs, such as Engelberg’s, Cancer Made Me A Shallower Person (2006) and Matsumoto’s My Diary (2008). The reader is there next to Tristram, invited into the intimacy of her experience for the duration.

Is it just another cancer memoir? It is another cancer memoir, but not just another. There are so many different types of cancer, with no two experiences or drawn interpretations the same and Probably Nothing offers a rich addition to the growing genre of graphic medicine literature. Tristram’s use of colour is striking. Speaking at Laydeez do comics (2014) she explained that initially she drew all the work in black line only. She was reluctant to add colour later, because she felt it would make it a bit less true or less real, but she is pleased with the result. The other two memoirs referenced here used the starkness of the black line. There is something about the use of watercolour wash in Probably Nothing that adds to the air of not really knowing what will happen next. The colour is allowed to bleed into the paper without control. In much the same way, the lives in the narrative unfold without control. The colour is not the loud, bright, bubble-gum positive outlook of Marisa Acocella Marchetto’s Cancer Vixen: A True Story (2009), which conveys a message of I will survive. In Tristram’s work, the colour seems rather to signify a quietly positive approach, an attitude of hopeful for the best but accepting of reality. The full colour and high quality production connotes comic as art. Matilda Tristram continues to work as an artist, trained in animation at the Royal College of Art, and lecturing at Kingston University. The publication clearly distances itself from an association with mainstream Superhero comics.

The drawing style is inviting for a non-comics audience, but I was not able to read it in one sitting. It is too relentless. I do not mean relentless in its gloom and trauma, for it is a story told with humour and lightness. It is tempting to use the term boring, but boring in a Mike Leigh film kind of way, in other words boring is not the right word either. It is to do with the disappointing reality of reality. As a reader, perhaps as a human, I cannot be alone in my hopefulness for a magic answer to life’s ills and pains. It is therefore constantly disappointing to find that there is no quick and easy solution. The message for me, if there was one, from Tristram’s narrative of her experience, is to take life little steps at a time in the face of adversity. There is a focus on the day to day, hour to hour– the importance and meaningfulness of the domestic. It is her use of humour that brings these details to life. The relationships with her partner and family are conveyed succinctly. For example, her mum falls asleep regularly in the waiting rooms, which is delightfully charming and funny. When they spend the day wandering round shops together, it is normal and unremarkable. Then Matilda notices the shop assistant noticing her colostomy bag. It is the noticing of the noticing in these instances that creates the gentle humour throughout the narrative. The attention to food also elevates the mundane. The reader experiences a stew or cheese on toast as more delicious than an everyday supper or lunch would normally be.

Every page has sixteen small panels and text is contained under the panels rather than integrated with the image, as is the more common comics convention. Sometimes the panels are slightly irregular, other times in uniform lines. But the 16 panel pages repeat and continue, as time does. Hilary Chute notes that trauma is often understood as repetition, which is what she says comics do so powerfully through the visual repetition. She endorses Cathy Caruth’s notion that “to be traumatized is precisely to be possessed by an image or an event” (Caruth quoted in Chute, 2010:183) It is Tristram’s repetition of the format of small panels of images and the repetition of herself within them which makes the comics form so successful in her presentation of her experience. It is her use of humour that makes this work not boring and not just another cancer memoir but a memorable, educational and moving story.

References

Acocella Marchetto, Marisa (2009) Cancer Vixen: A True Story New York: Pantheon Books

Chute, Hilary L. (2010) Graphic Women: Life Narrative & Contemporary Comics. New York: Columbia University Press

Engelberg, Miriam (2006) Cancer Made Me A Shallower Person. New York: Harper Collins

Matsumoto, Mio (2008) My Diary. London: Jonathan Cape

Tristram, Matilda (2014) Probably Nothing: A diary of not-your-average nine months. London: Viking, Penguin Books

Tristram, Matilda (2014) Laydeez do Comics, Foyles Bookshop, London. 15 September 2014

Williams, Zoe (2014) I Discovered I had colon cancer while I was pregnant. The Guardian [Online] 18 May 2013. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/may/18/discovered-colon-cancer-while-pregnant (Accessed on: 29 November 2014)

Nicola Streeten is an anthropologist-turned-illustrator and comics scholar, and the author of the graphic memoir Billy, Me and You (2011, Myriad Editions).