‘blindly pursuing early detection risks subjecting a third of diagnosed women to unnecessary harm.’

Jason Oke

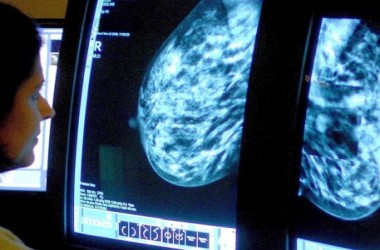

According to research led by the Barts Cancer Institute at Queen Mary University London, screening all British women over 30 years of age could result in 17,000 fewer ovarian and 64,000 breast cancers over a lifetime. Not only would screening multiple genes save lives but the cost of screening millions of women would be offset by savings made by preventing cancer. Testing for BRCA mutations is now common in women with a family history of cancer but screening all women is controversial because of the uncertainty in the risk of cancer and the balance between benefit and harm.

According to research led by the Barts Cancer Institute at Queen Mary University London, screening all British women over 30 years of age could result in 17,000 fewer ovarian and 64,000 breast cancers over a lifetime. Not only would screening multiple genes save lives but the cost of screening millions of women would be offset by savings made by preventing cancer. Testing for BRCA mutations is now common in women with a family history of cancer but screening all women is controversial because of the uncertainty in the risk of cancer and the balance between benefit and harm.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the two most important genes for breast and ovarian cancer. When functioning properly, the BRCA genes produce tumour suppressor proteins that help repair damaged DNA. If mutated, this function is lost and, consequentially, tumour suppressor proteins are not produced. This mutation leads to increased risk of ovarian and breast cancer in women.

So where does the harm come in?

Not all of the women with BRCA mutations will develop breast or ovarian cancer. In the language of genetics, the genotype (having the BRCA mutation) does not always predict the phenotype (developing cancer). The measure of how well the genotype predicts the phenotype is called the penetrance. Very few mutations have a penetrance approaching 100%, i.e. not every patient with the mutation gets the disease. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations do not have 100% penetrance, thus there will be women who have the mutation but will not develop cancer. These women are at risk of overdiagnosis; a diagnosis where the harms outweigh the benefits. For instance, a woman with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation that undergoes a prophylactic mastectomy, but does not develop breast cancer in her lifetime, has been overdiagnosed. Overdiagnosis and penetrance are inversely related, with fewer penetrant genes being more prone to overdiagnosis (Welch 2012). So how much overdiagnosis are we likely to get by screening for BRCA?

The press release claimed that the penetrance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 is between 69-72% for breast cancer over a lifetime. Thus, around a third of women with BRCA mutations would never develop breast cancer and will be overdiagnosed. This estimate of overdiagnosis, however, may be too conservative. In a systematic review of ten studies, the average penetrance of the BRCA genes, for women to develop breast cancer by age 70, was 57% and 49% respectively. Furthermore, some studies have shown that the risk varies among different populations, suggesting that other factors, such as exposure to oestrogen may play a part.

Whilst the presence of the BRCA genes undoubtedly increases a women’s risk of breast cancer, some women will gain no benefit from screening for them and instead will be exposed to unnecessary harms. The extent of the harm will depend on the action the women take following BRCA detection, ranging from anxiety to permanently disfiguring prophylactic mastectomy.

The discovery of BRCA genes has hugely advanced cancer diagnosis and treatment. Nevertheless, blindly pursuing early detection risks subjecting a third of diagnosed women to unnecessary harm.

Jason Oke is a Senior Statistician in the Nuffled Dept of Primary Care Health Sciences and Module Coordinator: Introduction to Statistics for Health Care Research on the Programme in Evidence-Based Health Care at the University of Oxford.

Acknowledgements: I’d like to thank Rafael Perera, Jack O’Sullivan and Brain Nicholson for helpful comments.

Conflicts of interest: none declared

References

Queen Mary University of London. Whole-population testing for breast and ovarian cancer gene mutations is cost-effective Title. Retrieved January 24, 2018, from http://www.qmul.ac.uk/media/news/2018/smd/whole-population-testing-for-breast-and-ovarian-cancer-gene-mutations-is-cost-effective.html

Chen, S., & Parmigiani, G. (2007). Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(11), 1329–1333. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066

National Cancer Institute. BRCA1 and BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing. Retrieved January 24, 2018, from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/brca-fact-sheet#r18

Gilbert Welch et al. (2012). Overdiagnosis: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health. Beacon Press.

Rebbeck, T. R., & Domchek, S. M. (2008). Variation in breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Research, 10(4), 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr2115