Use of oxygen in heart attack patients has remained uncertain for over 40 years, but clinical practice has only recently caught up with the evidence.

Carl Heneghan

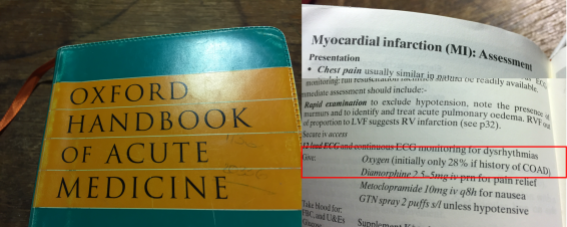

My Oxford Handbook of Acute Medicine – getting rather old now, like me – states to give oxygen in the initial management of myocardial infarction. Oxygen was routine during my training. Accumulating evidence, however, suggests use in all heart attack patients is not a good idea.

A recent trial in the New England Journal of Medicine found that routine use of supplemental oxygen in MI patients, who were not hypoxemic, did not reduce 1-year mortality.

The study randomised 6,629 patients (five times as many included in the Cochrane review) with suspected MI and an oxygen saturation of 90% to receive either supplemental oxygen (6 litres per minute for 6 to 12 hours) or ambient air. The trial found there as no difference in mortality at one year: 5.0% of patients (166/3311) died in the Oxygen group compared to 5.1% (168/3318) assigned to air (p=0.80).

Low levels of Oxygen (hypoxaemia) developed in 1.9% in the oxygen group compared with 7.7% in the ambient-air group and there was no difference in rehospitalisation rates within one year (3.8% Oxygen vs 3.3% air, p=0.33).

How does this fit in

More than ten years age a plethora of international guidelines widely recommended oxygen administration (see AARC 2002; AHA 2005 and Anderson 2007). For example, the 2003 European Society of Cardiology guidance recommended oxygen for patients with heart attacks associated with breathlessness or heart failure.

However, in 2007, the Scottish International Collegiate Guidelines (SIGN) recommended use of oxygen in only those patients who were hypoxaemic (< 90% saturation); from 2010 onwards, guidelines consistently became more cautious. In 2010, the American Heart Association guidelines reported there was insufficient evidence to recommend routine use in patients with uncomplicated Acute Coronary Syndrome without hypoxemia, recommending use in patients with saturations < 94%.

The 2015 AHA Update noted that: ‘supplementary oxygen has previously been considered standard therapy for the patient suspected of ACS, even in patients with normal oxygen saturation,’ and highlighted the lack of evidence in patients with normal oxygen levels.

A 2017 Cochrane review included five randomised controlled trials involving 1,173 patients with suspected or proven heart attack and compared patients given oxygen to those given air. Death rates were similar in both groups (relative risk for all-cause mortality 0.99, 95% CI, 0.50 to 1.95).

What does this mean

Oxygen is one the most commonly used drug in emergency medicine, however, there is no evidence that routine administration to all patients with heart attack improves outcomes. Moreover, RCT evidence has shown that therapy in patients with ST-elevation-myocardial infarction is associated with more extensive myocardial infarct size at six months.

Despite the continuing accumulation of evidence of ineffectiveness and associated harms, use in practice has been commonplace: a 2010 survey among doctors managing heart attack cases showed oxygen supplementation was given to 96% of patients. About 50% of practitioners at the time believed oxygen reduced death.

Clinical management has changed dramatically, particularly following guideline changes. The evidence, however, for the use of oxygen in heart attack has demonstrated a lack of effect for over 40 years: in 1976, a controlled trial published in the BMJ found no evidence of benefit from the routine administration of oxygen in uncomplicated myocardial infarction.

My Oxford Handbook is now an antique; I’ll keep it for nostalgic reasons, and bring it out from time to time to remind me that much of what we learn, can, and does change.

Carl Heneghan is Professor of EBM at the University of Oxford, Director of CEBM and Editor in Chief of BMJ EBM

Follow on twitter @carlheneghan

Competing interests

Carl has received expenses and fees for his media work including BBC Inside Health. He holds grant funding from the NIHR, the NIHR School of Primary Care Research, The Wellcome Trust and the WHO. He has also received income from the publication of a series of toolkit books published by Blackwells. CEBM jointly runs the EvidenceLive Conference with the BMJ and the Overdiagnosis Conference with some international partners which are based on a non-profit model.