By Lauren Forsyth, Kevin Booker, Adam Nathani, Karyn Kraemer, & Lisa Kirby

Athletes are bigger, faster, and stronger than ever; yet, they are still vulnerable to fatal injury. Complications from Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD) can ultimately lead an otherwise healthy athlete to a tragic fate. As misconceptions, and grey areas surrounding SCD continue, it is worthwhile to shed light on factors associated with this “silent killer.”

The aim of this blog is to promote awareness of Long-QT Syndrome and the risk of SCD in high performance athletes and to shed light on the possibility of inclusion if training is monitored and symptoms are controlled. Although it is a potentially fatal disorder, if detected, athletes may still be able to safely compete at the sports they love.

SCD Background

SCD is characterized as a non-traumatic, unexpected event that occurs due to sudden cardiac arrest. In order to be clinically considered SCD, the event must occur within 6 hours of previously witnessed typical health (Pugh, Bourke, & Kundian, 2011). Although SCD is still rare, “[it] is the leading cause of mortality among young athletes with an incidence of 1-2 per 100,000 athletes per [year]” (Pugh et al., 2011).

Long QT Syndrome and SCD

Long QT Syndrome and SCD

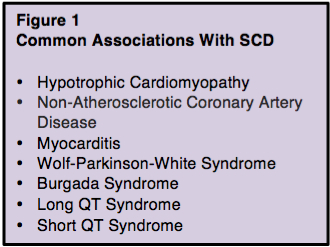

Numerous conditions are associated with SCD (figure 1); the focus for this article is the Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) — a disorder of the heart’s electrical system. The prolonged Q-T interval that can be detected via an electrocardiograph (ECG). This prolonged Q-T interval represents the slower than normal passing of the electrical signal through the ventricles of the heart. This congenital syndrome is often asymptomatic. In some cases people with LQTS experience unexplained faints, seizures, or arrhythmias. Sudden death can be the first clinical manifestation. According to Pugh et al. (2011), genetic testing is available for people with prolonged QT on ECG and those with a family history of SCD. This test is particularly useful for patients who do not exhibit any of the symptoms that are typically associated with the condition. The diagnosis of LQTS should be considered for any athlete with a history of losing consciousness.

Once it has been determined that an athlete has LQTS, lifestyle adjustments must be made with respect to their athletic participation. If an athlete has LQTS, he or she must be excluded from participating in all competitive sports. This ruling is consistent with the guidelines of the two main governing bodies regarding competitive sports participation for patients with LQTS, which are the 36th Bethesda Conference and the 2005 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines (Johnson and Ackerman, 2012). Although support for exclusion is extensive, opponents state restrictions placed on these athletes are too strict and the removal from sport can actually result in future debilitating effects on the athlete. According to Johnson and Ackerman’s article, a more formal structure with a pre-screening evaluation is needed that has acceptable sensitivity and specificity for those at risk of SCD. This multilevel pre-screening evaluation is an accurate way of determining the athlete’s exact magnitude of risk when competing in sport. When completed, it will highlight the patients that should not be participating in most sports, as indicated by “either (1) symptoms, or (2) a corrected QT interval (QTc) greater than 470 milliseconds (males) or 480 milliseconds (females)” (Johnson & Ackerman, 2012). If the corrected QT interval is less than the 470 or 480 milliseconds standard for males and females, respectively, the athlete can qualify for participation contingent upon an appropriately tailored therapy regiment including “β-blockers, …electrolyte and hydration replenishment, and minimization of core body temperature elevations” (Johnson & Ackerman, 2012). Athletes will also be advised to purchase an automatic external defibrillator as part of their sports equipment.

Despite being one of the main causes of SCD in competitive sport, “the estimated prevalence of this disorder is in the range of 1:5000 in the general population…with LQTS account[ing] for approximately 0.8% of the total deaths in young athletes” (Weaver-Pinson et al., 2009). The low prevalence rate suggests that considering alternatives for athletes is appropriate. Above all, recommendations should be individualized, “to assure that the specific recommendations as to type and intensity of athletic involvement are well understood and adequately discussed” (Weaver-Pinson et al., 2009). For minors, parental discussion is also vital.

To further support the participation of patients with controlled LQTS, there are well known cases of athletes who have decided to continue to play at a highly competitive level. One famous case is of Olympic swimmer Dana Vollmer who competed at the London Olympic Games in 2012. At the age of 15, Dana was diagnosed with LQTS after experiencing a dizzy spell while training. Vollmer and her family decided to implant a defibrillator in her chest, and closely monitor her training regimen so she could continue to swim. Dana is an inspiration to all athletes living with LQTS as her perseverance and bravery earned her a gold medal at the 2012 London Olympic Games. Although Dana now appears to have outgrown her LQTS symptoms, her decision to continue to swim “illustrates that some athletes can still participate in competitive sports despite cardiac defect” (O’Conner, 2012).

To further support the participation of patients with controlled LQTS, there are well known cases of athletes who have decided to continue to play at a highly competitive level. One famous case is of Olympic swimmer Dana Vollmer who competed at the London Olympic Games in 2012. At the age of 15, Dana was diagnosed with LQTS after experiencing a dizzy spell while training. Vollmer and her family decided to implant a defibrillator in her chest, and closely monitor her training regimen so she could continue to swim. Dana is an inspiration to all athletes living with LQTS as her perseverance and bravery earned her a gold medal at the 2012 London Olympic Games. Although Dana now appears to have outgrown her LQTS symptoms, her decision to continue to swim “illustrates that some athletes can still participate in competitive sports despite cardiac defect” (O’Conner, 2012).

***************************************************

Lauren Forsythe, Kevin Booker, Adam Nathani, Karyn Kraemer, and Lisa Kirby are undergraduate students in the School of Kinesiology at University of British Columbia. They are all avid sport and exercise enthusiasts that share a keen interest in chronic sports related injuries that plague the collegiate level.

References

Heart and Stroke Foundation. 2012. Web. 20 Oct. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.heartandstroke.com/site/c.ikIQLcMWJtE/b.3484075/k.F8EF/Heart_disease__What_is_Long_QT_Syndrome.htm

Johnson J, & Ackerman J, (2012). Competitive sports participation in athletes with congenital long qt syndrome. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 308(8):764-765. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.9334.

O’Conner A, (2012). Overcoming a heart condition to win olympic gold. The New York Times. Received from http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/07/31/overcoming-a- heart-condition-to-win-olympic-gold/?_r=0

Pugh, Andrew, John P. Bourke, and Vijay Kunadian. Sudden cardiac death among competitive adult athletes: a review. Postgraduate medical journal 88.1041 (2012): 382-390.

Wever-Pinzon O, Myerson M, & Sherrid M, (2009). Sudden cardiac death in young competitive athletes due to genetic cardiac abnormalities. Roosevelt Hospital Center Columbia University. 2; 17-23. Received from http://www.anakarder.com/sayilar/76/buyuk/17-23.pdf