By Cameron Knight

An article recently published in Veterinary Record Case Reports describes a case of fatal pneumothorax in a dog secondary to malformation of a single lung lobe. Within the published literature, most canine cases with a similar presentation are diagnosed as congenital lobar emphysema (CLE). However, in this particular dog, CLE was ruled out by a panel of veterinary and human paediatric pathologists. Histological lesions closely resembled congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM), a disease that is well recognised in children, but that has never been reported previously in any veterinary species. This report proposes that CPAM be considered in the differential diagnosis for canine spontaneous pneumothorax, and clarifies the distinction between CLE and CPAM.

The case describes an eight-month-old female boxer dog with progressive respiratory distress and no previous history of disease, trauma or toxin exposure. Pneumothorax was diagnosed and repeat thoracentesis and oxygen supplementation were performed for three days. CT confirmed bilateral pneumothorax and showed variably sized bullae in the right middle lung lobe, leading to a presumptive diagnosis of CLE.

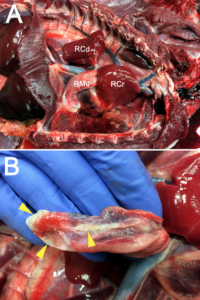

During anaesthetic induction for lung lobectomy, the dog developed cardiopulmonary arrest and died. A postmortem examination was performed, which confirmed severe bilateral pneumothorax with atelectasis of all lung lobes, and revealed a small, pale and flaccid right middle lobe with several ruptured bullae (Fig 1). The primary bronchus supplying this lobe was flattened, with a slit-like, rather than circular lumen. In addition, the right subclavian artery had an aberrant origin from the left subclavian artery, rather than from the brachiocephalic trunk.

Histological sections of the right middle lobe were difficult to recognise as lung tissue. They consisted predominantly of thick fibrovascular trabecular networks outlining collapsed, empty cavities lined by a simple cuboidal to simple squamous epithelium. All other lung lobes in the dog had normal histological architecture.

A diagnosis of CLE was ruled out histologically. CLE requires overinflated alveoli or hyperplastic alveoli, whereas the affected lobe in this dog lacked alveoli. Instead, after consultation with seven human paediatric pathologists, a diagnosis of CPAM-like disease was reached. The term CPAM refers to a spectrum of human airway malformations characterised by abnormal development of various portions of the tracheobronchial tree. CPAMs are well recognised and relatively common in people, and are characterised by multiple irregular pulmonary cystic structures lined by varying types of epithelium. The distinction between CLE and CPAM in humans is not merely academic. Importantly, CPAM may progress to malignant neoplasia, while CLE does not. Lobectomy is generally indicated for CPAM lesions, while CLE may resolve spontaneously and can often be managed conservatively.

While CPAM-like disease has never been reported in the veterinary literature, there are 11 reports of CLE in dogs. After reviewing these, it is possible that some reported canine cases of CLE may, in fact, represent CPAM-like disease. This case highlights the necessity for histological distinction between these two diseases, and describes a novel condition that may result in spontaneous pneumothorax in dogs.

More details, images and discussion about this case can be found here: http://vetrecordcasereports.bmj.com/content/4/2/e000378.full.